Advances in

eISSN: 2377-4290

Case Report Volume 15 Issue 3

Ophthalmology Department, Unidade Local de Saúde Entre Douro e Vouga, Santa Maria da Feira, Portugal

Correspondence: João Alves Ambrósio, Ophthalmology Department, Unidade Local de Saúde Entre Douro e Vouga, Rua Dr. Cândido Pinho 5, 4520-211, Santa Maria da Feira, Portugal, Tel +351 256 379 700

Received: October 22, 2025 | Published: November 14, 2025

Citation: Ambrósio JA, Teixeira P, Garcia M, et al. Delayed-onset cutibacterium acnes endophthalmitis after intravitreal dexamethasone implant in a pseudophakic diabetic eye: Case report and focused review. Adv Ophthalmol Vis Syst. 2025;15(3):107-110. DOI: 10.15406/aovs.2025.15.00496

Purpose: To report a culture-proven, delayed-onset Cutibacterium acnes endophthalmitis following intravitreal dexamethasone implant (Ozurdex®) and to highlight diagnostic and therapeutic nuances that distinguish infectious C. acnes inflammation from sterile post-implant reactions.

Case report: A 75-year-old pseudophakic man with proliferative diabetic retinopathy and neovascular glaucoma in the right eye presented with pain, redness, hypopyon, and vitritis seven weeks after Ozurdex. Initial management consisted of anterior chamber (AC) paracentesis and intravitreal vancomycin/ceftazidime, plus intensive topical therapy and systemic steroid taper. Because of an indolent but persistent course, a pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) was performed without IOL/capsular manipulation, combined with intravitreal vancomycin, triamcinolone, and aflibercept (for neovascular control). Prolonged incubation of the AC specimen grew C. acnes on day 11; other aerobic/fungal cultures were negative, and PCR was not performed. Inflammation resolved without relapse, and visual acuity improved to 20/30 at 18 months. A fluocinolone acetonide implant placed at 12 months for macular disease did not trigger recurrence.

Conclusion: Delayed-onset C. acnes endophthalmitis can occur after intravitreal steroid implantation and mimic sterile inflammation. Microbiologic confirmation often requires extended anaerobic incubation (≥10–14 days), with PCR as a useful adjunct where available. In carefully selected eyes without demonstrable capsular involvement, PPV-based management with intravitreal antibiotics—without immediate capsulectomy/IOL exchange—can achieve durable cure and good visual outcomes, provided close follow-up confirms long-term quiescence.

Keywords: cutibacterium acnes, delayed-onset endophthalmitis, dexamethasone implant, pars plana vitrectomy, pseudophakia, diabetic retinopathy

Postoperative or post-procedure endophthalmitis caused by Cutibacterium acnes (formerly Propionibacterium acnes) typically presents as an indolent, delayed-onset intraocular infection weeks to months after intraocular surgery. Its low virulence, biofilm formation on the capsular bag–intraocular-lens (IOL) complex, and slow anaerobic growth complicate timely microbiologic diagnosis and may delay appropriate therapy.1–3 Although C. acnes endophthalmitis is most often associated with cataract surgery, reports following intravitreal procedures—including sustained-release corticosteroid implants—remain uncommon and diagnostically challenging, as sterile post-implant inflammation can mimic infection.4–6

Because C. acnes is slow-growing and often sequestered, culture yield improves with extended anaerobic incubation for 10–14 days and enrichment in broth media; when cultures are equivocal, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can confirm infection more rapidly and with higher sensitivity.7 Therapeutically, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that pars plana vitrectomy (PPV)-based strategies achieve better visual improvement and lower retreatment rates than intraocular antibiotics alone, while the additional benefit of IOL removal or exchange remains individualized.4

We report a culture-proven C. acnes endophthalmitis arising seven weeks after an intravitreal dexamethasone implant (Ozurdex®) in a pseudophakic, diabetic eye with proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) and neovascular glaucoma (NVG). The case highlights diagnostic pitfalls, stepwise therapy from tap-and-inject to vitrectomy, and successful infection control without capsulectomy or IOL exchange.

Patient background

A 75-year-old man with a 20-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (HbA1c = 8.1%) and systemic comorbidities, including hypertension, cardiopathy, hyperuricemia, dyslipidemia, and early dementia, was under follow-up in the medical retina clinic for diabetic retinopathy with bilateral recurrent cystoid macular edema (CME).

He had undergone uncomplicated bilateral phacoemulsification with implantation of hydrophobic acrylic IOL in the capsular bag three years earlier. The right eye (OD) showed PDR with rubeosis iridis and NVG, while the left eye (OS) exhibited severe non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR).

His previous ocular treatments included multiple intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) injections—brolucizumab, ranibizumab, and aflibercept. There was no history of YAG capsulotomy, glaucoma surgery, or prior corticosteroid injection.

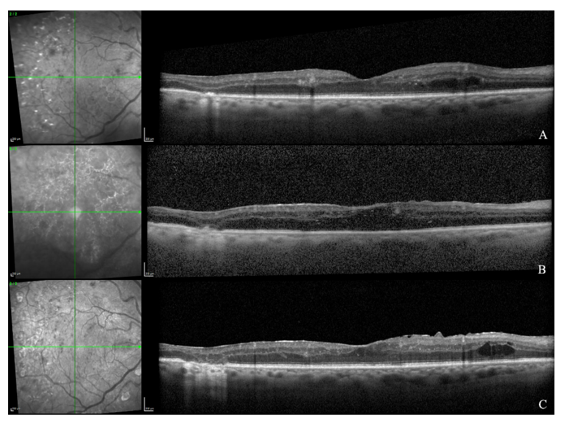

Visual acuity (VA) was 20/30 in the OD and 20/20 in the OS. At baseline, optical coherence tomography (OCT) of both eyes demonstrated disorganization of the retinal inner layers (DRIL) with scattered intraretinal cystoid spaces (Figure 1A).

Figure 1 OCT of the OD at baseline (A), five days after PPV (B), and at the last follow-up (C).

(A) Baseline shows DRIL with intraretinal cysts

(B) Early postoperative imaging reveals media-related signal attenuation with preserved foveal architecture and a mild ERM

(C) Final follow-up demonstrates an ERM with foveal contour distortion, persistent DRIL, and rare residual cysts.

Index procedure

The OD received an intravitreal dexamethasone implant (Ozurdex®) for recurrent CME. At the two-week follow-up, examination revealed only a small subconjunctival hemorrhage at the injection site. Intraocular pressure (IOP) was 15 mmHg, and no signs of intraocular inflammation were observed.

Presentation

Seven weeks after the injection, the patient presented with pain and redness in the OD. VA was counting fingers (CF) at 1 m. Slit-lamp examination revealed conjunctival hyperemia, a 1/4-inferior hypopyon, endothelial deposits, and a marked anterior chamber (AC) inflammatory reaction, with a centered IOL. IOP was 24 mmHg. Fundus visualization was precluded by media opacity. B-scan ultrasonography demonstrated dense vitreous echoes without evidence of retinal detachment.

The patient was taken to the operating room, where an AC paracentesis was performed for microbiological analysis, followed by intravitreal injection of vancomycin (1.0 mg/0.1 mL) and ceftazidime (2.25 mg/0.1 mL). He was subsequently admitted for intensive topical therapy with fortified antibiotics (vancomycin and cefazolin hourly), atropine, and prednisolone acetate 1%. Oral prednisone 60 mg daily was initiated and tapered over time. No systemic antibiotics were administered.

Early course

On the first postoperative day, VA in the OD remained CF at less than one meter, with a 1/3-inferior hypopyon and an IOP of 16 mmHg. The initial aqueous humor (AH) culture yielded no microbial growth.

During hospitalization, AC inflammation persisted with a relatively indolent course. On the eighth hospital day, a PPV was indicated. A 25-gauge core PPV was performed, leaving the peripheral vitreous intact and without manipulation of the posterior capsule. At the conclusion of surgery, intravitreal injections of aflibercept (2 mg, for neovascular glaucoma), vancomycin (1 mg), and triamcinolone acetonide (2 mg) were administered.

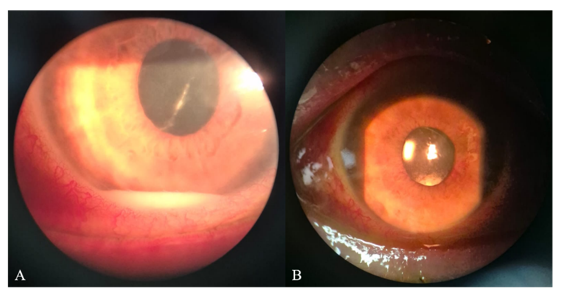

On the first postoperative day following PPV, VA in the OD was CF. Slit-lamp examination revealed a 2 mm hypopyon, a clear pupillary center, and residual fine rubeosis iridis; (Figure 2). Five days after PPV, OCT of the OD demonstrated diffuse signal attenuation due to postoperative media opacity, with overall preservation of the foveal architecture and outer retinal bands, and a mild epiretinal membrane (ERM) (Figure 1B).

Figure 2 Anterior segment findings following pars plana vitrectomy with intravitreal injections of aflibercept, vancomycin, and triamcinolone in the right eye.

(A) Postoperative day 1: corneal haze, 2-mm inferior hypopyon, clear pupillary center, rubeosis iridis, and a centered IOL

(B) Postoperative day 5: small residual inferior hypopyon, 1+ AC cells, fine rubeosis iridis, and a centered IOL.

Microbiology

Prolonged incubation of the AH sample yielded C. acnes at day 11; all aerobic/fungal cultures were negative. No PCR or susceptibility testing was performed, consistent with typical delayed growth requiring >10 days for positivity.7

Postoperative evolution

At day fifteen, VA improved to 20/200. The hypopyon had resolved, with persistence of 1+ AC cells and fine rubeosis. IOP measured 12 mmHg. A mild anterior vitreous haze and small macular hemorrhages were noted.

During hospitalization, he developed diabetic decompensation requiring higher insulin doses. No other systemic events occurred.

The patient was discharged on topical moxifloxacin six times daily, prednisolone acetate 1% six times daily, and atropine twice daily, and lubricating drops, along with a tapering course of oral prednisone starting at 40 mg daily.

At the first outpatient follow-up, VA improved to 20/125. The AC was clear, rubeosis remained mild, and IOP was 14 mmHg.

No additional aqueous taps were performed, and the OD was considered sterile and clinically stable.

Follow-up

At six months, the OD remained quiet, with gradual clearing of the media and no signs of recurrent inflammation. VA was 20/40. Fundus examination revealed moderate NPDR in both eyes. At twelve months, a fluocinolone acetonide intravitreal implant (Iluvien®) was placed to address persistent macular disease. The procedure was uneventful, and no recurrence of intraocular inflammation was observed.

At eighteen months, VA was 20/30 in the OD and 20/25 in the OS. IOP was stable at 13 mmHg and 15 mmHg, respectively. Both corneas were clear, with no evidence of rubeosis. Mild anterior capsule fibrosis was noted in the OD, but the IOL remained well centered and stable. At the last follow-up, OCT of the OD revealed an ERM with mild foveal contour distortion, persistent DRIL, and rare residual intraretinal cysts (Figure 1C).

Differential diagnosis: Sterile post-ozurdex inflammation vs c. acnes infection

Sterile inflammation after dexamethasone implant usually occurs within days, responds promptly to steroids, and yields negative cultures.8 In contrast, C. acnes endophthalmitis shows delayed onset (weeks-months), partial steroid response, and slow-growing organism detection. Additional clues include vitreous involvement and, when visible, intracapsular white plaque, although absence of a plaque does not exclude infection—particularly in eyes with haze or intense AC reaction.7 Our case favored infection: onset 7 weeks post-implant, persistent hypopyon and vitritis, culture positivity at day 11, and lasting remission after vitrectomy and antibiotics.

Microbiology considerations

Management rationale

Empiric tap-and-inject with vancomycin and ceftazidime remains standard initial therapy. A recent meta-analysis of nine series demonstrated that PPV-based strategies yield significantly greater visual improvement and lower retreatment rates than intraocular antibiotics alone (odds ratio ≈ 8.9 favoring PPV).4 The incremental benefit of IOL removal or exchange is possible but not definitive due to study heterogeneity.4

Because our patient had no visible capsular plaque, uncertain microbiology at surgery, and ischemic comorbidity (PDR/NVG), we chose core PPV sparing the periphery. Intravitreal vancomycin, triamcinolone (for inflammation control), and aflibercept (for NVG) achieved rapid improvement and durable quiescence without IOL or capsular intervention. The subsequent tolerance of a fluocinolone implant 12 months later strongly suggests eradication of infection.

Relationship between cutibacterium acnes and the capsular bag

This biofilm affords C. acnes protection from host immune surveillance and from the bactericidal concentrations of antibiotics achievable within the aqueous and vitreous. The relative hypoxia inside the closed capsular bag and the absence of vascular clearance mechanisms further favor chronic survival. Over time, intermittent bacterial shedding or antigen release into the aqueous humor provokes low-grade, recurrent inflammation that can mimic sterile uveitis and typically responds only transiently to corticosteroids.

Clinically, this sequestration manifests as delayed-onset endophthalmitis—often weeks to months after surgery—with a characteristic whitish intracapsular plaque visible on or behind the posterior capsule in many cases. The plaque represents accumulated organisms, inflammatory cells, and lens material. Its absence, however, does not exclude infection, especially when visualization is hindered by corneal haze or a dense anterior chamber reaction.

Understanding this capsular-bag tropism is crucial because it explains both the indolent clinical course and the frequent need for surgical eradication. When the bacterial reservoir lies within the capsular bag, simple tap-and-inject or vitrectomy may suppress inflammation temporarily but rarely achieves sterilization without addressing the biofilm niche. Conversely, in eyes without visible capsular involvement or recurrent inflammation, as in the present case, conservative PPV with intravitreal antibiotics can be sufficient—provided long-term monitoring confirms stability.

Given this tropism for the capsular bag–IOL complex and the organism’s biofilm-mediated latency, local corticosteroid exposure may alter host–pathogen dynamics and unmask subclinical infection, as discussed below.

Relationship to intravitreal steroid implant

In eyes harboring sequestered C. acnes within the capsular bag, intravitreal corticosteroids can reduce local immune surveillance and clinically ‘unmask’ a previously quiescent nidus, precipitating delayed-onset endophthalmitis. Cutibacterium acnes infection may be triggered or unmasked after trans-conjunctival procedures such as steroid implantation, either by contamination or by local immunosuppression permitting latent bacterial proliferation.

Role of capsulectomy and IOL management

Traditional series advocate posterior capsulectomy ± IOL removal/exchange to eliminate biofilm.1,2 The meta-analysis confirms overall superiority of PPV-based treatment but finds only inconclusive additional benefit from IOL removal once PPV and antibiotics are performed.4 Therefore, in eyes without plaque and with high surgical risk, conservative PPV may suffice—exactly as illustrated here. Lack of recurrence after 18 months, despite later corticosteroid exposure, supports this tailored approach.

Visual and anatomic outcome

Despite severe onset, vision recovered to 20/30 with no relapse. OCT changes (DRIL, macular thickening) reflect chronic diabetic pathology rather than infection sequelae.

Limitations

Vitreous and capsular samples were not cultured, and PCR was unavailable; thus confirmation of complete eradication is indirect. Nonetheless, prolonged follow-up and absence of recurrence—including after corticosteroid re-challenge—argue for effective control. This outcome aligns with isolated reports of success using PPV ± antibiotics alone in eyes lacking capsular plaque.4

Delayed-onset C. acnes endophthalmitis may follow intravitreal steroid implantation and mimic sterile inflammation. Clinicians should maintain suspicion when inflammation arises >4 weeks post-injection and persists despite therapy. Extended anaerobic incubation and, where available, PCR are critical for diagnosis. In eyes without capsular plaque, PPV with intravitreal antibiotics can achieve a durable cure without IOL exchange, provided close follow-up confirms long-term quiescence.

None.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

No funding or sponsorship was received for the conduct of this study.

©2025 Ambrósio, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.