Advances in

eISSN: 2377-4290

Research Article Volume 15 Issue 3

1Ophthalmology Department, Niamey National Hospital, Niger

2Ophthalmology Department, Amirou Boubacar Diallo National Hospital, Niamey, Niger

Correspondence: Abba Kaka Hadjia Yakoura, Ophthalmology Department, Niamey National Hospital BP: 238, Niger, West Africa

Received: September 20, 2025 | Published: November 6, 2025

Citation: Yakoura AKH, Lamyne AR, Dan Jouma AML, et al. Management of orbital cellulitis in the ophthalmology department of the national hospital of Niamey. Adv Ophthalmol Vis Syst. 2025;15(3):97-101. DOI: 10.15406/aovs.2025.15.00494

Introduction: Orbital cellulitis is a rare but potentially life-threatening infection of the orbit, usually secondary to sinus, cutaneous, or dental infections.

Methodology: This retrospective descriptive study analyzed 18 cases of orbital cellulitis managed at the Ophthalmology Department of the National Hospital of Niamey over an eight-month period. The objective was to describe the clinical presentation and management approaches in our setting.

Results: The mean age of patients was 25.7 ± 12.4 years, with a predominance of children and adolescents (<20 years: 66.7%). Males were more frequently affected, with a male-to-female ratio of 2.03:1. Predisposing factors included diabetes mellitus, malnutrition, and prior use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Eyelid edema was present in all patients, while 50% had retroseptal involvement. Orbital computed tomography was performed in 55% of cases and confirmed the extent and severity of infection. All patients received systemic antibiotic therapy, occasionally combined with corticosteroids. Surgical drainage was required in 72% of cases. Clinical outcomes were generally favorable, with one case of panophthalmitis requiring enucleation.

Conclusion: Although limited by the small sample size, this study emphasizes the need for early diagnosis and appropriate management of orbital cellulitis to prevent severe ocular complications. Further multicenter studies with microbiological confirmation are recommended to refine management strategies in resource-limited settings.

Keywords: orbital cellulitis, sinusitis, antibiotic therapy, surgical drainage, Niger, pediatric ophthalmology

Orbital cellulitis is an acute infection of the orbital fat and connective tissue, most commonly arising secondary to infections of the ear, nose, throat, or dental origin. It constitutes a serious ophthalmic condition associated with risks of visual impairment and intracranial complications. Two principal clinical forms are distinguished: preseptal cellulitis, limited to structures anterior to the orbital septum and generally responsive to systemic antibiotics, and postseptal (or true orbital) cellulitis, in which infection extends posterior to the septum. The latter is a diagnostic and therapeutic emergency due to its potential to progress rapidly to orbital abscess, cavernous sinus thrombosis, meningitis, or permanent vision loss.1–3

Diagnosis of orbital cellulitis is primarily clinical, relying on characteristic signs such as eyelid swelling, pain, chemosis, proptosis, restricted ocular motility, and fever. However, clinical findings alone may not reliably differentiate between preseptal and postseptal involvement. In this context, orbital computed tomography (CT) is considered the gold-standard imaging modality: it allows the clinician to confirm the diagnosis, delineate the extent of infection, detect abscess formation, and rule out intracranial extension.4,5

Management of orbital cellulitis is predominantly medical, combining broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotic therapy (targeting both aerobic and anaerobic pathogens) and, in selected cases, systemic corticosteroids once infection control is underway. When there is evidence of abscess formation, worsening despite medical therapy, or threat to vision, surgical drainage is indicated.2,6,7

Despite declines in incidence in high-income settings thanks to improved vaccination and earlier access to medical care, orbital cellulitis remains an important cause of ocular morbidity in sub-Saharan Africa. According to the World Health Organization, periorbital and orbital infections still contribute significantly to ophthalmic disease burden in children in low-resource settings, accounting for approximately 8–12 % of hospitalized ocular infectious cases.8 In Niger, there is a paucity of published data on orbital cellulitis. Therefore, this study aims to characterize the clinical presentation, management, and outcomes of orbital cellulitis cases seen at the Ophthalmology Department of the National Hospital of Niamey.

The study was conducted in the Ophthalmology Department of the National Hospital of Niamey. It was a descriptive cross-sectional study carried out over an eight-month period, from October 1, 2023, to June 1, 2024. The study population consisted of all patients seen in ophthalmology consultation during this period. All cases of orbital cellulitis diagnosed and managed in the department were included, provided that the patients or their legal guardians gave informed consent to participate.

Patients who did not provide consent, as well as those with orbital tumors, necrotizing periorbital fasciitis, or those lost to follow-up, were excluded from the study. The variables analyzed included sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, origin, and occupation), predisposing factors (such as ENT infections, dental infections, cutaneous or endocrine disorders, trauma, animal bites, and insect stings), and clinical features (reasons for consultation and findings on clinical examination). Paraclinical variables comprised biological test results and imaging studies. Management parameters included medical and/or surgical therapeutic approaches, while outcome variables covered treatment results and possible complications.

Information was collected through patient interviews (or from legal guardians in the case of minors) and by reviewing medical records, using a pre-established data collection form. Data entry and statistical analysis were performed using Epi Info™ version 7.2.2.6 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA).

During the study period, from October 1, 2023, to June 1, 2024, a total of 5,760 patients consulted at the Ophthalmology Department of the National Hospital of Niamey. Among them, 18 patients were managed for orbital cellulitis, representing a hospital frequency of 0.31%. By extrapolating this number over a 12-month period, the estimated annual incidence was approximately 27 cases.

Annual incidence = 8 months/18 cases×12 months=27 cases/year

Sociodemographic characteristics

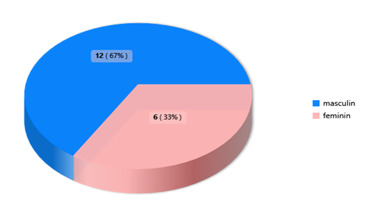

The mean age of patients was 25.7 years (range: 2 months–68 years; median: 15 years). The 10–20 age group was the most represented (38.9%) (Figure 1). Males predominated (67%), with a male-to-female ratio of 2.03 (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Distribution by sex.

Male sex predominated, with 12 patients (67%). The male-to-female sex ratio (M/F) was 2.03.

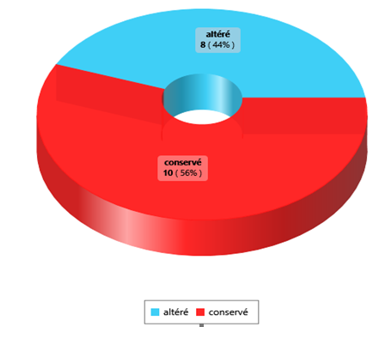

Triggering factors and general condition Ear, nose, and throat (ENT) conditions were the main reason for admission (52.9%), followed by oral and dental conditions (17.6%) and eye and skin trauma (11.8%) (Table 1). More than half of the patients were in good general health (56%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Distribution according to the general condition of patients.

Among the 18 patients, 10 (56%) had a preserved general condition.

|

Triggering factors |

Frequency (N) |

Percentage (%) |

|

Dental infection |

3 |

17.65 |

|

Ear, nose, and throat (ENT) infection |

9 |

52.94 |

|

Insect bite |

2 |

11.76 |

|

Septicemia |

1 |

5.88 |

|

Oculocutaneous trauma |

2 |

11.76 |

|

Total |

17 |

100 |

Table 1 Distribution of patients according to triggering factors

Male sex predominated, with 12 patients (67%). The male-to-female sex ratio (M/F) was 2.03.

Among the 18 patients, 10 (56%) had a preserved general condition.

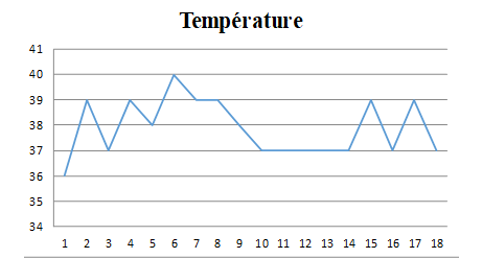

Half of the patients had a fever ≥ 99.5°F (mean: 98.6°F; range: 93.2–104.4°F) (Figure 4). The condition was most often unilateral (61.1%) (Table 2). Visual acuity assessment showed variability ranging from light perception to 20/20, with assessment impossible in four children due to age (Table 3).

Figure 4 Distribution according to body temperature.

In our series, half of the patients presented with fever (temperature > 37.5 °C), with values ranging from 36 °C to 40 °C. The mean temperature was 37.88 °C.

|

Involvement |

Unilateral |

Bilateral |

|

|

Laterality |

OD |

OS |

OU |

|

Frequency (N) |

1 (5.55) |

10 (55.56) |

7 (38.89) |

Table 2 Distribution of patients according to the affected eye

|

Visual acuity |

Right eye (OD) |

Left eye (OS) |

|

LP |

– |

1 |

|

HM |

– |

1 |

|

CF |

– |

4 |

|

1/10 (≈ 20/200) |

1 |

– |

|

2/10 (≈ 20/100) |

– |

– |

|

3/10 (≈ 20/70) |

– |

– |

|

4/10 (≈ 20/50) |

1 |

– |

|

5/10 (≈ 20/40) |

– |

– |

|

6/10 (≈ 20/32) |

– |

1 |

|

7/10 (≈ 20/30) |

1 |

– |

|

8/10 (≈ 20/25) |

– |

1 |

|

9/10 (≈ 20/22) |

1 |

1 |

|

10/10 (20/20) |

– |

1 |

|

Not Assessable |

4 |

7 |

|

Total |

8 |

17 |

Table 3 Distribution of visual acuity according to the WHO Classification

Light Perception (LP), Hand Motion (HM), Counting Fingers (CF)

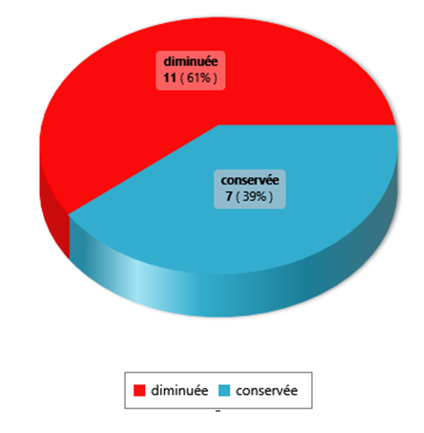

Decreased oculomotor function was observed in 61% of cases (Figure 5). Exophthalmos was present in eight patients, including one case of grade III, according to the simplified clinical classification (Table 4).

Figure 5 Distribution according to ocular motility.

In our study, 11 patients (61%) had reduced ocular motility in the affected eyes.

|

Grade of Exophthalmos |

OD |

OS |

Absent |

Total |

|

Grade I |

3 |

2 |

- |

5 |

|

Grade II |

- |

5 |

- |

5 |

|

Grade III |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

|

None |

- |

- |

10 |

10 |

|

Total |

3 |

8 |

10 |

21 |

Table 4 Distribution of exophthalmos according to the simplified clinical classification

Regarding the adnexa, eyelid swelling was constant (100%), associated with ecchymosis (88.9%), purulent secretions (83.3%), false ptosis (66.7%), and chemosis (66.7%) (Table 5).

|

Clinical signs |

Frequency (N) |

Pourcentage (%) |

|

Palpebral ecchymosis |

16 |

88.89 |

|

Palpebral swelling |

18 |

100 |

|

Pseudoptosis |

12 |

66.67 |

|

Chemosis |

12 |

66.67 |

|

Purulent discharge |

15 |

83.33 |

Table 5 Findings from the examination of ocular adnexa

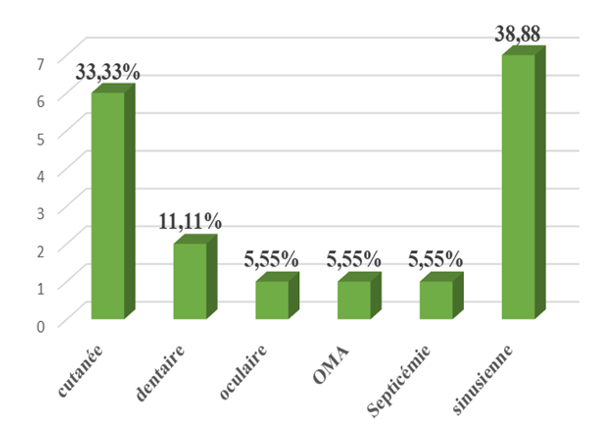

Extraorbital subcutaneous extension was noted in 4 patients (22.2%). Sinus origin was the most common (39%), followed by skin involvement (33%) (Figure 6). In our series, half of the patients presented with fever (temperature > 37.5 °C), with values ranging from 36 °C to 40 °C. The mean temperature was 37.88 °C. In our study, 11 patients (61%) had reduced ocular motility in the affected eyes.

Figure 6 Distribution by origin.

Probable Origin of Cellulitis: Sinus involvement was most common in 7 (39%) patients. These were all patients who had orbital cellulitis. This was followed by skin involvement, which was found in 6 patients, or 33%.

Probable Origin of Cellulitis: Sinus involvement was most common in 7 (39%) patients. These were all patients who had orbital cellulitis. This was followed by skin involvement, which was found in 6 patients, or 33%.

Additional investigations

Hyperleukocytosis was observed in 60% of cases. CRP was positive in all patients (6–442 mg/mL). Bacteriological examination, performed in only one patient, revealed a polymicrobial culture. Hyperglycemia was observed in 3 patients, including one with known diabetes. Renal function impairment was present in 40% of the cases examined.

Radiologically, a standard X-ray revealed dental caries. Orbital-facial CT scans, performed on 10 patients, revealed orbital cellulitis (60%), preseptal cellulitis (30%), or a mixed form (10%). Chandler's classification showed a balanced distribution between preseptal and retroseptal forms (Figure 7).

Management

All patients received dual parenteral antibiotic therapy (amoxicillin-clavulanic acid + metronidazole), followed by oral therapy. Systemic corticosteroid therapy was administered to 5 patients, combined with analgesic and local treatment (eye drops, ointments, eye washes).

Surgery was necessary in 72% of patients (incision and drainage, debridement in cases of necrosis). One case of evisceration was performed in a diabetic patient with complicated panophthalmitis.

Outcome

The outcome was favorable in 94.4% of cases. Only one patient presented a major complication with panophthalmitis.

Orbital cellulitis is rare in everyday practice. In our series, 18 cases were observed over eight months (0.31%), a frequency comparable to that reported by Baldé Ak in Guinea9 and slightly lower than that reported by Gouèta in Burkina Faso.10 These variations can be explained by the sample sizes and the duration of the studies.

This condition affects all ages, with a predominance in children and adolescents, linked to the immaturity of the immune system and orbital vascularization.11 In our study, the average age was 25.7 years, with 66.7% of patients under the age of 20, a finding similar to African series.2,10,12

The distribution by gender shows a male predominance (sex ratio: 2.03), consistent with the observations of Belghmaidi in Morocco and Wane in Senegal.13,14 Contributing factors include immunosuppression, diabetes, and malnutrition.2,15 Prior use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs aggravated clinical signs in 61% of patients, consistent with Saadouli and Harding.16,17

Sinusitis remains the main cause (39%), followed by skin conditions (33.3%) and less frequent dental infections.2,10,18–22 Clinical examination consistently reveals eyelid edema, while chemosis, exophthalmos, and limited eye movement vary depending on whether the lesion is preseptal or retroseptal.5,23,24

Paraclinical tests confirm the diagnosis and determine the severity. Hyperleukocytosis was present in 60% of patients and elevated CRP in all patients, a rate higher than that reported by Gouèta.10 CT scans were performed in 55% of patients, a proportion comparable to the data reported by Mekni Manel.4 Treatment is based on appropriate antibiotic therapy, administered on an outpatient basis for simple forms and parenterally for severe forms, with an effective combination of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and metronidazole.4–6 Corticosteroid therapy was used in 38.5% of hospitalized patients, less than in Gouèta's series.10 Surgical treatment is reserved for severe complications. In our study, 72% of patients underwent drainage and one case required evisceration, proportions comparable to those reported by Mekni Manel4 and Konan Aj.2

The prognosis is generally favorable if diagnosis is early and treatment is appropriate. One case of panophthalmitis required evisceration, highlighting the importance of rapid treatment and close monitoring.25 This study has certain limitations, notably the small sample size and short follow-up period, which limits the generalizability of the results. In addition, some clinical and paraclinical data were not systematically available, and the lack of long-term follow-up does not allow for a full assessment of late complications and visual prognosis.

This study shows that it affects all ages, with a predominance in children and adolescents, and that it is most often secondary to a sinus infection. Early consultation and appropriate treatment generally lead to a favorable outcome, as observed in the majority of our patients, with only one case of visual loss.

We would like to thank all the medical and paramedical staff of the Ophthalmology Department of the National Hospital of Niamey for their collaboration, as well as the patients and their families for their trust.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the development of this work. ABBA KAKA H.Y designed the study. LAMYNE A.R, DAN JOUMA A. M L contributed to data collection, analysis, and interpretation of results. MAMADOU I.C, GARBA A.S, SOUMAILA M D, AMZA A contributed to writing and critical revision. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability

The data used and analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

None.

©2025 Yakoura, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.