International Journal of

eISSN: 2573-2889

Mini Review Volume 8 Issue 1

1Master’s student in Plant Metabolism Physiology at the Graduate Program in Plant Genetic Resources, Agricultural Sciences Center, Federal University of Santa Catarina, Brazil

2Associate Professor, Department of Crop Science, Agricultural Sciences Center, Federal University of Santa Catarina, Brazil

Correspondence: Elinton Soares Pontes, Master’s student in Plant Metabolism Physiology at the Graduate Program in Plant Genetic Resources, Agricultural Sciences Center, Federal University of Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, SC, Brazil

Received: June 27, 2025 | Published: July 8, 2025

Citation: Pontes ES, Gris T, Seledes RM, et al. Influence of LED light spectra on the in vitro development of Cattleya crispa Lindl. Int J Mol Biol Open Access. 2025;8(1):47-51. DOI: 10.15406/ijmboa.2025.08.00197

In recent decades, in vitro propagation has benefited from the use of light-emitting diodes (LEDs), whose spectral quality directly influences plant development. This study evaluated the effect of different light spectra on the in vitro germination of Cattleya crispa Lindl., an orchid species endemic to Brazil with high ecological importance. For 70 days, seeds were cultivated in MS medium under four lighting treatments: blue, red, white, and a blue+red LED combination, using fully sealed flasks. The variables analyzed were germination rate, number of oxidized protocorms, protocorms with leaf primordia, and fresh biomass of the seedlings. Red light resulted in the highest germination rate (86.55%), an effect possibly related to the activation of phytochromes and the induction of gibberellin biosynthesis, both essential for breaking seed dormancy. C. crispa seeds exhibited positive photoblastism, with greater sensitivity to red light. On the other hand, blue light favored the highest accumulation of fresh biomass (0.87 g per experimental unit) and the greatest formation of protocorms with leaf primordia, standing out in the initial growth of seedlings. The combination of blue and red LEDs promoted balanced morphogenesis, optimizing the formation of photosynthetic structures. Red light was also associated with higher oxidation levels, suggesting increased oxidative stress, whereas seeds cultivated under blue light exhibited lower oxidation rates, likely due to the activation of antioxidant mechanisms that protected the protocorms. It is concluded that blue light, either alone or combined with red light, provides better conditions for micropropagation, supporting the conservation and commercial production of C. crispa, an orchid species of great ecological and ornamental value.

Keywords: Cattleya crispa, in vitro germination, LEDs, phytochrome, protocorm

Orchids represent one of the most specialized and diverse plant groups on the planet, having adapted to a wide range of habitats and ecological niches. These plants exhibit remarkable morphological, anatomical, and physiological adaptations to various climates and establish complex interactions with specific pollinators in different regions.1,2 Such characteristics give orchids a crucial role in maintaining the stability of forest ecosystems, especially due to their high degree of specialization and capacity to survive under extreme and oligotrophic environmental conditions.3 In Brazil, most orchid species are found in mountainous regions of the Atlantic Forest, one of the most biodiverse biomes in the world. However, this biome is among the most threatened by human activities, with only 12.4% of its original coverage remaining in good conservation status.4 The destruction of natural habitats and indiscriminate collection for commercial purposes have significantly reduced the populations of several species, including those belonging to the genus Cattleya. The genus Cattleya comprises approximately 187 species, in addition to numerous varieties and hybrids.5 Among them, Cattleya crispa Lindl. stands out for its ornamental value and for being an endemic species to Brazil, predominantly occurring in the states of Rio de Janeiro, Minas Gerais, and São Paulo.6 Estimates from the National Center for Flora Conservation indicate that natural populations of C. crispa may decline by up to 30% over the next 30 years, reinforcing the need for effective conservation strategies.

Natural propagation of this species occurs asexually via lateral buds or sexually through seeds produced in capsules.7 However, orchid seeds lack endosperm, a structure essential for storing nutrients needed for germination. Thus, in situ germination depends on association with mycorrhizal fungi, which provide essential compounds for seedling development. Given the increasing environmental threats and the difficulty of establishing these symbiotic interactions, in vitro micro propagation has been widely used as a promising biotechnological strategy for the conservation and large-scale production of orchid seedlings.8,9 This technique enables seed germination without the need for mycorrhizae, allows the production of pathogen-free plants, and facilitates the propagation of species with limited natural reproduction. Among environmental factors that influence plant growth and development, light plays a central role in regulating morphological, physiological, and anatomical processes. Light intensity, direction, and spectral quality are key determinants in plant life cycle stages such as stem elongation, leaf expansion, flowering, and fruiting.10 Specifically, wavelengths in the blue (400–500 nm) and red (600–700 nm) ranges directly affect photosynthesis and metabolism, triggering specific responses mediated by photoreceptors such as phytochromes and cryptochromes.11,12 Although fluorescent lamps have traditionally been used in micro propagation, these light sources present limitations, including high heat production, low spectral efficiency, and short lifespan.13,14 In contrast, light emitting diodes (LEDs) emerge as an advantageous alternative, offering longer lifespan, spectral specificity, energy efficiency, and minimal heat emission.15 Previous studies have demonstrated that the combination of blue and red LEDs can increase biomass and root number in Cattleya walkeriana.16 Similar results were observed in Schomburgkia crispa, where 75% red light promoted greater leaf and root production. In this context, the present study aimed to evaluate the impact of different LED light spectra on the in vitro germination of Cattleya crispa Lindl. Based on these results, we intend to improve propagation techniques for this species, providing support for its conservation and large-scale production.

A sample containing N fish can be obtained from a fish population either by simple random sampling or by some form of selective sampling. In a typical case N is large, but the theory presented here holds in principle for any positive integer value. On the other hand, the population from which the sample is drawn is assumed to be infinitely large. For example, fish living in a particular rearing pond are seen as a sample from the potentially infinitely large population of similar fish that could be produced in the given pond and under conditions similar to present ones.

The experiment was conducted at the Laboratory of the Center for Research in Biotechnology and Plant Development (NPBV), at the Agricultural Sciences Center of the Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC), from November 2021 to February 2022.17 Seeds of Cattleya crispa Lindl. were collected in September 2021 from plants cultivated in a greenhouse at the Botanic Institute of the State of São Paulo (23° 38' 30.7" S 46° 37' 14.2" W). Seed viability was tested following the methodology proposed by Lakon18 and adapted by Suzuki et al.19 For this, 1 µl of a 0.5% solution of 2,3,5triphenyltetrazolium chloride was applied to histological slides containing C. crispa seeds and kept in the dark at 24 °C for 48 hours. In this test, H+ ions released during cellular respiration of living embryonic tissues reduce the tetrazolium salt to a red-colored compound, indicating 90% seed viability. Under laminar flow hood conditions, 10 mg of seeds were disinfected following the protocol adapted by Suzuki et al.20 Seeds were soaked in autoclaved distilled water for 10 minutes, followed by immersion in 0.5% active chlorine sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) for another 10 minutes, and then rinsed three times with autoclaved distilled water. After disinfection, using an automatic micropipette set at 100 µl, the seeds were inoculated into 240 ml glass flasks containing 30 ml of MS medium21 supplemented with 2 ml l⁻¹ of Morel vitamins,22 30 g l⁻¹ sucrose, 2.0 g l⁻¹ activated charcoal, and solidified with 6.0 g l⁻¹ agar. The pH was adjusted to 5.8 ± 0.1 prior to autoclaving at 120 °C for 20 minutes, and the flasks were sealed with polypropylene lids. The seeds were maintained for 70 days in a growth room under a 16-hour photoperiod at 25 ± 2 °C with light irradiance provided by two TEC LAMP® tubular LEDs, each emitting 50 µmol.m⁻².s⁻¹, positioned 50 cm above the flasks.

Evaluated variablesAfter 70 days of in vitro culture, the following variables were analyzed: seed germination, determined by the development of the embryo into a structure known as a protocorm, as described by Rasmussen et al.23 The germination percentage was calculated using the formula: G = (N/A) × 100, where G = germination percentage, N = number of germinated seeds, and A = total number of seeds. Additionally, total fresh mass per experimental unit (in grams), the number of protocorms with leaf primordia, and the number of oxidized protocorms (identified by brownish coloration) were recorded.

Experimental design and statistical analysisThe experiment was set up in a completely randomized design (CRD), consisting of four treatments corresponding to different light spectra [(white LED, red LED, blue LED, and a combination of red + blue LEDs at a ratio of 60% to 40%, respectively, from TEC LAMP®)], with seven replicates per treatment. The experimental unit consisted of 100 µl of a solution containing 10 mg of seeds. Data were subjected to Tukey’s test for statistical analysis using the SISVAR software24 to verify the normality of the analyzed variables.

The germination of Cattleya crispa Lindl. seeds was significantly influenced by the spectral quality of light, directly affecting the initial establishment of seedlings. The treatment with red LEDs resulted in the highest germination rate, reaching 86.55%, a value statistically superior to the other treatments according to Tukey’s test at a 5% probability level (Table 1). The spectral quality of light proved to be a determining factor for the in vitro germination of Cattleya crispa Lindl., corroborating studies investigating the role of light in the early development of orchids. The results indicated that seeds exposed to red LEDs exhibited the highest germination rate, followed by those under white, blue, and the blue and red LED combination. This pattern suggests that red light has a positive effect on activating physiological processes that regulate germination, a phenomenon widely documented in the literature. Ribeiro,25 when studying Cattleya walkeriana, reported that both red and blue LEDs, as well as their combinations, promoted high germination rates, close to 80%. Similar results were reported by Soares et al.26 for Cattleya nobilior Rchb.f., Cattleya lundii (Rchb.f. & Warm.) Van den Berg, and Brassavola tuberculata Hook, with germination rates of 98.5%, 96.6%, and 62.0%, respectively. These findings reinforce that light quality directly influences germination, with the red wavelength being particularly efficient in this process.

|

Light germination spectrum (%) |

Fresh mass leaf primordia |

Oxidized protocorms |

||

|

|

|

(g) |

(No.) |

(No.) |

|

Blue LED |

52.78 b |

0.87 a |

283.28 a |

106.14 b |

|

Red LED |

86.55 a |

0.8 a |

151.28 c |

222.14 a |

|

Blue + Red LED |

47.01 b |

0.81 a |

239.57 ab |

134.14 b |

|

White LED |

60.95 ab |

0.63 b |

198.57 bc |

124.28 b |

|

CV (%) |

32.96 |

13.27 |

16.11 |

13.28 |

Table 1 Effect of different LED light spectra on seed germination percentage, fresh mass (g), number of leaf primordia, and number of oxidized protocorms of Cattleya crispa Lindl after 70 days of in vitro culture

Means followed by the same letter in the column do not differ by Tukey’s test at 5% probability.

In the present study, C. crispa seeds exhibited positive photoblastism, responding more expressively to red light. This effect may be attributed to the activation of phytochromes, pigments sensitive to wavelengths around 660 nm, which, when stimulated, promote structural changes essential for the onset of embryonic development.27 Phytochrome activation stimulates gibberellin biosynthesis, regulating germination and dormancy breaking. Additionally, although blue LEDs promoted lower germination rates, this spectrum is directly related to chlorophyll synthesis and the stimulation of initial seedling growth, playing a crucial role in subsequent stages of plant development.11,12 These effects were confirmed in this study, where blue light was a key factor in the formation of leaf primordia in C. crispa. Thus, the combination of blue and red LEDs can be an efficient strategy to optimize both germination and early seedling growth, balancing the positive effects of each light spectrum. The discrepancy between treatments suggests that specific adjustments in light spectral quality may be an effective strategy to optimize the in vitro cultivation of orchids, especially for species with high endemism and environmental vulnerability, such as Cattleya crispa. The results reinforce the potential of LEDs as an alternative light source for micro propagation due to their ability to target specific wavelengths, providing benefits in terms of energy efficiency and plant development control. Leite & Hebling,28 when studying the in vitro germination of Cattleya warnerii seeds, also highlighted the crucial role of red light in increasing germination rates, corroborating the findings of the present study. Germination under all light regimes tested highlights the ecological plasticity of orchid seeds, as described by Benzing et al.3,29 and Kauth et al.,30 which associate this adaptation with survival in low-light natural environments.

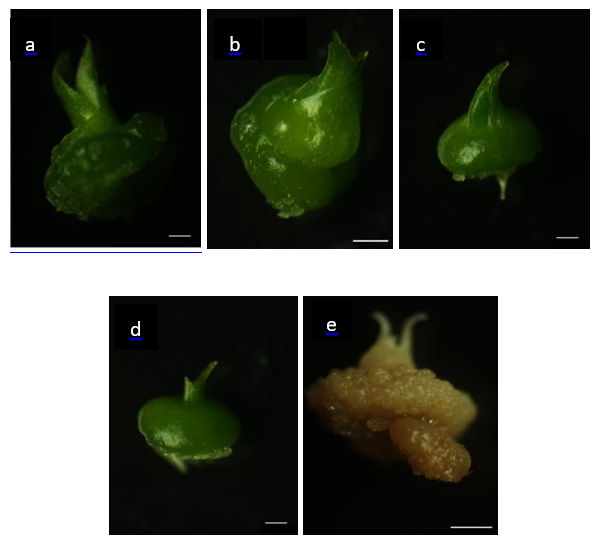

Regarding fresh mass, the treatment with blue LEDs resulted in the highest accumulation (0.87 g per experimental unit), significantly differing from the white LED treatment (0.63 g). Blue light is associated with the activation of cryptochromes and phototropins, which regulate processes such as photosynthesis, stomatal opening, and cell division, promoting greater efficiency in plant growth.11,31 Additionally, the effect of blue light on plant water potential may have contributed to the increase in fresh biomass observed in this study. The synergy between blue and red light was also evident in the formation of protocorms with leaf primordia, with the blue LED treatment being the most efficient (283.28 individuals), followed by the blue and red LEDs (239.57) and white LEDs (198.57) (Figure 1a, c, d). These results are consistent with Naznin et al.32 and Chung et al.33 who highlight the importance of these spectra in regulating photosynthesis, chlorophyll production, and morphogenesis. Although blue light was more effective for fresh mass accumulation and leaf primordia formation, red light played a relevant role in leaf expansion and biomass accumulation (Figure 1b), as reported by Heo et al.,34 where the dry weight of Calendula officinalis seedlings was significantly increased under monochromatic red light or in combination with fluorescent light. These wavelengths, alone or in combination, promote balanced seedling development. Studies by Ribeiro25 and Hung et al.35 also indicate that red, blue, and combined LEDs are effective in the early development of Cattleya walkeriana and Cattleya nobilior, supporting the findings of the present study. However, the red LED treatment showed the highest oxidation rate of protocorms (222.14), significantly higher than that observed under blue LEDs (106.14). Oxidation is associated with the release of phenolic compounds and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which, at high concentrations, compromise cell membrane integrity.36,37 While red light is essential for germination and morphogenesis, its effect on the regulation of phytochemical synthesis, such as phenolic compounds, may intensify oxidative processes.38,39 In addition to influencing leaf pigmentation and mesophyll organization, plant responses to light also directly affect chloroplast structure and functionality (Figure 1e). These organelles dynamically adjust their energy and metabolic performance according to environmental conditions, developing mechanisms to minimize the side effects of photosynthesis, such as ROS production, an inevitable byproduct of converting light into energy in the presence of oxygen.40 Conversely, blue light demonstrated a protective effect against oxidation by inducing antioxidant mechanisms and the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, as highlighted by Naznin et al.,32 who found that LED lighting increased growth, pigment content, and antioxidant capacity in vegetables under controlled conditions. These mechanisms are essential to mitigate the harmful effects of oxidation and ensure greater protocorm viability, favoring healthier early development. Despite providing a broad spectrum, white LEDs showed limitations in terms of photomorphogenic efficiency. Alterations in mesophyll tissues and stomatal functionality were associated with this light source, as described by Faria et al.41 and Hung et al.,35 suggesting that excess energy may elevate ROS levels, exceeding cellular regeneration capacity and negatively impacting seedling development (Figure 1).

The results of this study showed that different light spectra significantly affect germination, early development, and oxidation levels of Cattleya crispa Lindl. protocorms. Blue light, either alone or combined with red light,42 provided the most favorable conditions for the in vitro propagation of this species. In particular, blue light was effective in reducing oxidation levels and stimulating protocorm growth and development, standing out as the most suitable option for optimizing the initial cultivation of C. crispa. The findings of this study provide important insights for improving micropropagation techniques for C. crispa, contributing to large-scale production and the conservation of this threatened species.

None.

The authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

©2025 Pontes, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.