Journal of

eISSN: 2373-633X

Research Article Volume 12 Issue 6

1Faculdade Pernambucana de Saúde (FPS), Avenida Mal. Mascarenhas de Morais, Brazil

2Instituto de Medicina Integral Professor Fernando Figueira (IMIP), Rua dos Coelhos, Brazil

Correspondence: Fernanda Keller Leite Araújo, Faculdade Pernambucana de Saúde (FPS). Avenida Mal. Mascarenhas de Morais, 4861–Imbiribeira, Recife–PE. CEP:51150-000, Brazil

Received: October 30, 2021 | Published: December 29, 2021

Citation: Araújo FKL, Soares IG, Santos PMC, et al. Cervical cancer as a marker of exclusion to health services and social vulnerability. J Cancer Prev Curr Res. 2021;12(6):179-185. DOI: 10.15406/jcpcr.2021.12.00477

Objectives: Verify the conditions of access/use of the health system by women with uterine cervical cancer (UCC) and their families, seeking to geolocate and identify the sociodemographic profile.

Methods: Cross-sectional study involving cancer patients admitted to IMIP between 2016 and 2019. The variables data were related to the sociodemographic profile, preventive examination, Human Papillomavirus (HPV) and the influence of the UCC diagnosis on the search for preventive and screening measures by women's family members. It was opted for the stratification according to the mesoregions of the State.

Results: Out of the 285 participants, 55,8% live in municipalities in the 1st Region of Health, while the Florest Zone mesoregion has the higher performance of biopsies in the public sector (59,5%). The sociodemographic analysis highlights non-white race (77,7%) and only 6,8% with complete higher education. The knowledge about performing the Pap smear reached 88,9% and the disinformation about the HPV reached 44,4%. Related to the influence of cancer, 76,3% said that the young family members underwent HPV vaccination and 82,2% related their diagnosis to search for preventive in family members over 25 years old.

Conclusion: The UCC has dimensions that reveal regional and social inequalities, and should be understood not only as an oncological indicator, but essentially as an indicator of social vulnerability and health care needs.

Keywords: uterine cervical neoplasms, social inequity, health services accessibility

Cervical (CCU) or cervical cancer is the fourth most common type of cancer in women worldwide.1 Studies indicate that almost nine out of ten deaths related to this disease occur in less developed regions, where the risk of dying from CC, before the age of 75, is three times higher.2 In Brazil, CC is the third most frequent tumor and the fourth cause of death in women from cancer. In the Northeast region, without considering non-melanoma skin tumors, CC is the second type of cancer that most affects the female population, with an incidence rate of 20.47 cases per 100,000 women. In the state of Pernambuco, for 2018, 1030 new cases were estimated and, of these, 180 are expected to occur in the city of Recife, with crude incidence rates of 20.84 and 20.52/100,000, respectively.3

This theme falls within the scope of women's health, an area considered essential to actions in the Unified Health System (SUS). Controlling the CCU is a priority on the country's health agenda, whose public policies have been developed since the mid-1980s, and is part of the Ministry of Health's Strategic Action Plan for Combating Non-Communicable Diseases (NTCDs) ( MS) of 2011.4,5 However, despite government efforts allied to academic production and the performance of health professionals, in addition to CC being the cancer with the greatest potential for prevention, associated with the slow evolution of initial cervical lesions from about twenty years to the invasive phase4, it it is still an important public health problem in Brazil, being the one that most causes death of young women (15 to 44 years of age).6

The structuring of prevention actions should consider that, according to the literature, the most important risk factor for the development of high-grade intraepithelial lesions (precursors of the CCU) and of the CCU is infection by the Human Papillomavirus (HPV) with its oncogenic subtypes , being associated with practically all cases of cervical cancer.6-8 Other factors associated with the development of CC include sexual behavior and lifestyle habits, such as early onset of sexual activity, multiplicity of sexual partners, multiparity, prolonged use of oral contraceptives, history of sexually transmitted diseases such as Chlamydia trachomatis infection, and smoking.9,10

Among the CC prevention strategies are educational measures, vaccination, condom use, in addition to screening, diagnosis and treatment of subclinical lesions.7,11 In this sense, studies show that early detection of injuries, as well as accurate diagnosis of the degree of injury and early treatment, are essential elements for prevention.12 The strategy adopted for tracking CC in the country is to periodically perform a cervical smear cytopathological examination, known as the Papanicolaou test, allied, since 2014, to the implementation of the tetravalent vaccine against HPV in the vaccination schedule.5,7 The effectiveness of the CC control program is achieved by guaranteeing the organization, integrity and quality of services, as well as the treatment and follow-up of patients.7 Thus, the later its detection, the lesser the chances of reducing its damage, a condition that scales the importance of preventive actions.4

In this sense, it is highlighted, in general, that in order to achieve greater effectiveness in actions to prevent cervical cancer in Brazil, it is necessary to improve the levels of adequacy of this programmatic action in the basic health network, there is a need to promote substantial improvements, especially the improvement and implementation of registration systems for activities carried out in the Basic Health Units (UBS), the qualification of teams and the increase in the supply of inputs and materials necessary for the full development of actions.13 Literature analysis shows that areas with great social inequality have higher mortality from CC, this phenomenon has several explanations: individuals' lifestyle, offer and accessibility to screening, treatment and social stratification services based on the economic model adopted by the country.14

In this perspective, considering the mortality and incidence of CC, as well as its prevention potential, this study aims to analyze the conditions of access/use of the health system by women with cervical cancer and their families, as well as geolocate the cases, identify the socio-demographic profile and describe the conditions associated with prevention, diagnosis, access and continuity of care related to the CC of women attended at the IMIP.

A cross-sectional observational study involving patients with cervical cancer admitted through the Oncology Patient Reception and Screening Center (Nat onco), at the Instituto de Medicina Integral Prof. Fernando Figueira (IMIP), located in the city of Recife, capital of Pernambuco, located in the Northeast region of Brazil, in the period between 2016 and 2019. For the composition of the sample, patients were considered as inclusion criteria.

Aged 18 years or over and diagnosed with CC, confirmed through the colpocytopathological examination in follow-up during the study period. Patients with a previous diagnosis of another type of neoplasm or with metastatic disease were excluded. Thus, the population of this study is composed of 285 women.

The data collection process, carried out by the students involved, was carried out from the analysis of the medical records of the participating women, obtained through the registration data present in Nat Onco, and through an interview guided by a structured questionnaire. For patients who did not attend the consultations, an active search was performed by telephone call.

The variables corresponded to dimensions related to the sociodemographic profile (age, skin color, education, marital status, occupation, religion and place of residence); the preventive exam (knowledge about the exam, performance and frequency with which it was performed); to HPV (knowledge about the virus and the vaccine); and the influence of CC diagnosis on the search for preventive and screening measures by family members of women affected by cancer (vaccination against HPV and Pap smear tests).

The data collected for each variable evaluated were organized and tabulated using the Microsoft Excel program. After tabulation, consolidation and statistical analysis were performed using the Statistical Package of Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 20.0 for Windows. A descriptive analysis of the data was carried out, evaluating the frequency of distribution of the variables. Data were expressed in absolute and relative frequency distribution and presented in tables and figures. It was decided to stratify the interviewees according to the mesoregion of the State, namely: agreste, sertão, forest zone, São Francisco and the metropolitan region of Recife (RMR). To verify associations between categorical variables, the Likelihood Ratio test was used to measure whether there are differences between the proportions of responses, according to the mesoregion. The significance level adopted was 5%, that is, p<0.05.

This study respected the ethical precepts established by Resolution 510/16, of the National Health Council, which defines the Guidelines and Norms for Research involving Human Beings. It was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the IMIP, under Certificate of Presentation for Ethical Appreciation (CAAE): 21990719.2.0000.5201. The anchor study entitled "Continuing Education in Oncology at the IMIP" is also listed as approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee.

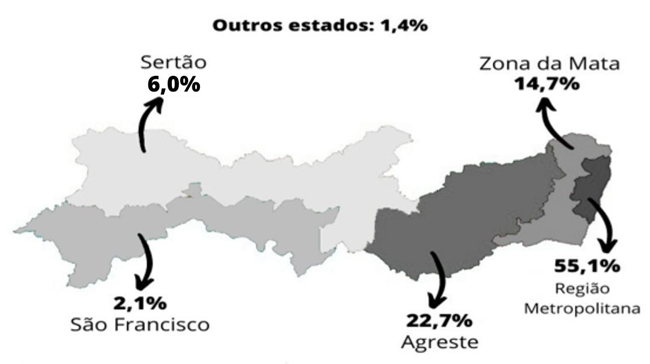

The study sample consisted of 285 women seen at the oncology clinics of the IMIP, between 2016 and 2019, who had colpocytopathological alterations compatible with CCU, distributed in all Regional Health Departments (GERES), stratified according to the mesoregion of the State. Among the participants, the majority, 159 (55.8%), live in municipalities located in I GERES, 37 (13%) in IV, 32 (11.2%) in III and 4 (1.4%) in others States. Regarding the distribution according to the municipalities stratified by mesoregion, it appears that the participants are distributed in all mesoregions, with 157 (55.1%) concentrated in the RMR, 59 (22.7%) in the agreste and 42 (14.7%) in the forest zone (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Distribuicao das pacientes com CCU atendidas no IMIP segundo Mesorregiao, Pernambuco, 2016-2019.

It is worth emphasizing the importance of the histopathological examination for an accurate diagnosis and adequate follow-up of the CC. In this sense, it was predominant, 147 (51.6%), the performance of the biopsy in a public agency, while 61 (21.4%) in a private service and 77 (27.0%) had no record of the place of performance in the system of patient registration at the IMIP. However, the analysis by mesoregions shows differences, with the performance in private service prevailing in the sertão, 6 (35.3%), and in the São Francisco mesoregion, 3 (50.0%).

With regard to the sociodemographic profile, it was possible to observe the following data: there was a predominance of women with CC aged between 40 and 49 years, 47 (29%), and the average age was 49.1 years; women primarily reside in urban areas, 265 (93%). To deepen this analysis, interviews were carried out and of the 285 women, 162 (56.8%) carried out the interviews completely, 78 (27.4%) contact was not possible, because the woman did not answer or the phone was turned off. available in the registry, 29 (10.2%) died and 16 (5.6%) refused to respond.

Of the 162 respondents, the majority reported having: married/consensual union, 81 (50.0%), Catholic religion, 83 (51.2%), and non-white race, 126 (78.2%) . The results prevailed in all mesoregions and these variables did not show statistically significant differences (p>0.05), as shown in table 1. Regarding education (Table 1), it is observed that 54 (33.3%) interviewees have only completed elementary school or equivalent, and only 11 (6.8%) completed higher education. As for the situation by mesoregion, the metropolitan region has a significant concentration of women with higher education and despite constituting only 8 (8.4%) of the women in this mesoregion, they represent 72.2% of the interviewees who have this education. Those who do not have education correspond to 19 (11.7%), highlighting the wild, 9 (25.7%) and the sertão, 1 (14.7%). For this variable there were differences with statistical significance (p=0.043).

|

Variable |

wild |

RMR |

Sao Francisco |

Sertao |

Zona da Mata |

Total |

P-value1 |

|

n(H) |

n(H) |

n(H) |

n(H) |

n(H) |

n(%) |

||

|

Marital status Casada Consensual Union |

16(45,7) |

47(49,5) |

2 (66,7) |

4(57,1) |

12 (54,5) |

81 (50,0) |

0,605 |

|

Divorce Separated |

1 (2.9) |

9(9,5) |

0(0,0) |

0 (0,0) |

3(13,6) |

13(8,0) |

|

|

Single |

14(40,0) |

34(35.8) |

1 (33.3) |

3 (42.9) |

7(31.8) |

59(36.4) |

|

|

Widow |

4(11,4) |

5 (5,2) |

o (0,0) |

0 (0,0) |

0(0,0) |

9(5,6) |

|

|

schooling |

|||||||

|

None |

9(25,7) |

6(6,3) |

1 (33.3) |

1 (14.3) |

2(9.1) |

19(11.7) |

0,043* |

|

Former elementary primary |

7 (20,0) |

15(15,8) |

o (0,0) |

o (0,0) |

5(22,7) |

27 (16,7) |

|

|

fundamental thesis or equivalent |

11(31.4) |

26(27,4) |

1 (33.3) |

4(57.1) |

12(54,5) |

54(33.3) |

|

|

Average or equivalent |

7 (20,0) |

38 (40,0) |

o (0.0) |

1 (14,3) |

2(9,1) |

48 (29,6) |

|

|

Superior (3’degree) - Complete |

1 (2.9) |

8(8.4) |

1 (33,3) |

0 (0,0) |

1(4.5) |

11(6,8) |

|

|

Superior (3’degree) - Incomplete |

0 (0.0) |

2(2,1) |

o (0,0) |

1 (14,3) |

0(0,0) |

3 (1.9) |

|

|

Religion Catholic |

22 (62,9) |

43 (45,3) |

2(66.7) |

6(85,7) |

10(45.5) |

S3 (51,2) |

0.392 |

|

Spiritist |

0 (0,0) |

1 (1,0) |

0 (0,0) |

o (0,0) |

0(0,0) |

1 (0,6) |

|

|

Evangelical |

12(34,3) |

36(37,9) |

1 (33,3) |

1 (14.3) |

9 (40,9) |

59(36,4) |

|

|

I don't have a religion |

1 (2.9) |

15(15,8) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

3 (13.6) |

19(11.7) |

|

|

Rafa |

0 (0,0) |

2(2,1) |

0(0,0) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0,0) |

2(1.2) |

0.1 |

|

Yellow |

|||||||

|

White |

13(37,1) |

15(15,8) |

0 (0.0) |

3(42.9) |

5(22.7) |

36(22,3) |

|

|

Indigenous |

0 (0,0) |

0(0,0) |

1 (33,3) |

0 (0.0) |

0(0,0) |

1 (0,6) |

|

|

black |

1 (2.9) |

12(12.6) |

0(0,0) |

0 (0.0) |

1 (4.5) |

14(8,6) |

|

|

The screen |

21 (60,0) |

66(69,5) |

2 (66,7) |

4(57,1) |

16(72,7) |

109 (67,3) |

|

|

Occupation retired |

4(11,4) |

8(8,4) |

0(0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

3(13.6) |

15(9,2) |

0,641 |

|

No works |

15(42,9) |

27(28,4) |

2 (66,7) |

4(57,1) |

9 (40,9) |

57 (35.2) |

|

|

work away from home ilio |

12(34,3) |

42 (44,2) |

1 (33,3) |

2 (28,6) |

6(27,3) |

63 (3S,9) |

|

|

Housework |

4(11.4) |

18(19,0) |

0 (0.0) |

1 (14.3) |

4(18.2) |

27(16.7) |

|

|

Total |

35 (100.0) |

95 (100,0) |

3 (100.0) |

7 (100.0) |

22 (100.0) |

162 (100.-0) |

|

Table 1 Distribution of patients with CCU attended at the IMIP according to marital status, education, religion, race and occupation, stratified by mesoregion, Pernambuco, 2016-2019

1- Likelihood Ratio independence test; * statistically significant.

The results indicate occupation outside the home as the main form of work, 63 (38.9%), followed by 57 (35.2%) who did not work, 27 (16.7%) in jobs domestic workers and 15 (9.2%) retired. The majority, 42 (44.2%), of women who work outside the home are in the metropolitan region. In terms of race/color, the “non-whites” were reported by 126 (77.7%) patients, for these variables there were no statistically significant differences (Table 1).

As for the screening process and early diagnosis, highlighting the performance of the preventive exam (Papanicolaou), the variables related to knowledge and adherence to the exam, presented in table 2, show that 144 (88.9%) women had knowledge about the Papanicolaou, of which 90 (94.7%) were from the metropolitan mesoregion. The agreste was the mesoregion with the highest percentage of patients who were unaware of the exam, totaling 8 (22.9%). The previous frequency of performing the annual exam was predominant, 70 (60.9%). However, a significant number of women, 47 (29.0%) reported that they did not undergo the exam, and they mostly justify, 22 (46.9%), for not being informed of the need for the exam, 16 (34.0 %) due to fear or embarrassment, 8 (17.0%) could not inform the reason and 1 (2.1%) due to carelessness. In the wild mesoregion, the highest occurrence of women who did not undergo the exam was identified, 15 (43.0%).

|

Variable |

Agreste |

Metropolitana |

Sao Francisco |

Sertao |

Zona da Mata |

Total |

p-value |

|

n(H) |

n(%) |

n(H) |

n(%) |

n(%) |

n(H) |

||

|

Previous knowledge about preventive examination |

|||||||

|

No |

S(22,9) |

5(5,3) |

1(33,3) |

0(0,0) |

4(18,2) |

18(11.1) |

0,021" |

|

Sim |

27(77.1) |

90(94,7) |

2(66.7) |

7 (100,0) |

18(81,8) |

144 (88,9) |

|

|

Total |

35(100.0) |

95 (100,0) |

3 (100,0) |

7(100,0) |

22 (100,0) |

162 (100,0) |

|

|

Priority of the performance exam |

|||||||

|

With an interval > 3 years |

0(0.0) |

2(2.1) |

0(0.0) |

1 (14.3) |

0(0.0) |

3(1.9) |

0,203 |

|

every 2 years |

5(14.2) |

6(6,3) |

0(0.0) |

0(0,0) |

1 (4,5) |

12(7,4) |

|

|

Every 3 years |

1 (2,8) |

2(2,1) |

0(0,0) |

1 (14,3) |

2(9,0) |

6(3,7) |

|

|

More than once a year |

0(0,0) |

1(1,1) |

0(0.0) |

0(0.0) |

0(0.0) |

1 (0,6) |

|

|

No results |

7(20.0) |

11(11,6) |

0(0.0) |

0(0,0) |

5(22.7) |

23 (14,2) |

|

|

Todoano |

7 (20,0) |

50(52,6) |

2(66,6) |

4(57,1) |

7(31,9) |

70(43,2) |

|

|

did not perform |

15(43,0) |

23 (243) |

1(33.4) |

1 (14,3) |

7(31.9) |

47(29.0) |

|

|

Total |

35 (100,0) |

95 (100,0) |

3 (100,0) |

7(100,0) |

22 (100,0) |

162 (100,0) |

|

|

Reason for not taking the exam |

|||||||

|

not muffin of the need for the exam |

10(43.5) |

8(533) |

3(42.8) |

1 (100,0) |

0(0.0) |

22(46.9) |

0,201 |

|

Fear of the exam or embarrassment |

S(34,S) |

4(26,7) |

3(42,8) |

0(0,0) |

1 (100,0) |

16(34,0) |

|

|

Neglect |

1(4.3) |

0(0,0) |

0(0.0) |

0(0,0) |

0(0.0) |

1 (2,1) |

|

|

NS NR |

4(17,4) |

3(20,0) |

1(14,4) |

0(0,0) |

0(0,0) |

8(17.0) |

|

|

Total |

23(100.0) |

15 (100.0) |

7(100.0) |

1 (100.0) |

1 (100.0) |

47 (100.0) |

|

|

Age at which the preventive examination started |

|||||||

|

<25 years old |

14(70,0) |

65(90,3) |

1(50,0) |

3 (50,0) |

8(53,3) |

91 (79.1) |

0,009" |

|

Between 25 and 65 years old |

4 (20.0) |

7(9,7) |

1 (50.0) |

3 (50.0) |

7(46.7) |

22(19,1) |

|

|

> 65 years old |

1(5,0) |

0(0,0) |

0(0,0) |

0(0,0) |

0(66,7) |

1 (0,9) |

|

|

Do not remember |

1(5,0) |

0(0,0) |

0(0,0) |

0(0,0) |

0(0,0) |

1 (0,9) |

|

|

Total |

20 (100,0) |

72 (100,0) |

2 (100.0) |

3 (100,0) |

15 (100,0) |

115(100,0) |

|

Table 2 Distribution of patients with CCL attended at the IMIP according to vanaveu related to the realization of preventive examination, stratified by mesorregido, Pernambuco, 2016-2019

Regarding the age at onset, the majority, 91 (79.1%), reported having performed before 25 years old and for this variable, the concentration of interviewees living in municipalities in the RMR (p=0.009) can be seen, with differences with statistical significance.

Considering the strong association of HPV infection with CC, data on this dimension are shown in Table 3. The high lack of knowledge about HPV, reported by 72 (44.4%) patients, is noteworthy. The analysis of this variable by mesoregion shows worse results in the municipalities of the sertão, 5 (71.4%), and agreste, 23 (65.7%), with statistically significant differences (p=0.018). The health post was reported as the main source of information about the vaccine, 92 (64.8%), followed by television, 77 (54.2%). When asked about the purpose of vaccination against HPV, 121 (84.2%) responded positively, and of these, 117 (93.6%) had a correct answer. The results also show, regarding the target audience of vaccination, that “boys and girls” represented the main answer of the interviewees, 81 (56.2%), but 44 (30.6%) do not know/did not answer this question (table 3).

|

Variable |

Agreste |

Metropolitana |

Sao Francisco |

Sertao |

Zona da Mata |

Total |

p-value |

|

n(H) |

n(H) |

n(H) |

n(%) |

n(%) |

n(H) |

||

|

Know HPV |

|||||||

|

No |

23(65,7) |

31(32,6) |

1(33,3) |

5(71,4) |

12(54,5) |

72(44,4) |

0,005- |

|

Sim |

12(343) |

64(67,4) |

2(66,7) |

2(28,6) |

10(45,5) |

90(55,6) |

|

|

Total |

35 (100.0) |

95 (100,0) |

3 (100,0) |

7(100,0) |

22 (100,0) |

162 (100,0) |

|

|

Know the HPV vaccine |

|||||||

|

No |

7(20,0) |

6(6,3) |

2(66.7) |

0(0,0) |

3 (13,6) |

18(11,1) |

0,018- |

|

Sim |

28(S0,0) |

S9 (93,7) |

1 (33,3) |

7(100,0) |

19(86,4) |

144(88,9) |

|

|

Total |

35 (100,0) |

95 (100,0) |

3(100,0) |

7(100,0) |

22 (100,0) |

162 (100,0) |

|

|

Source of information about the HPV vaccine (if the previous answer is YES)** |

|||||||

|

Health Center |

17(60,7) |

59(663) |

1 (100,0) |

5(71,4) |

10(52,6) |

92(64,8) |

0,725 |

|

Television |

17(60,7) |

46(51,7) |

0(0,0) |

4(57,1) |

10(52,6) |

77(543) |

0,696 |

|

IMIP |

4(14,3) |

19(213) |

0(0,0) |

0(0,0) |

2(10,5) |

25(17,6) |

0,306 |

|

Healthcare professional |

8(28,6) |

21(23,6) |

0(0,0) |

1 (14,3) |

5(26,3) |

35(24,6) |

0,850 |

|

Friends |

1(3,6) |

5(5,6) |

0(0,0) |

0(0,0) |

1(5,7) |

7(4,9) |

0,903 |

|

Others |

0(0,0) |

4(4,5) |

0(0,0) |

0(0,0) |

2(10,5) |

4(2,8) |

0,636 |

|

Knowledge about the HPV vaccine public aho |

|||||||

|

just memnas |

5(17,9) |

9(10,1) |

0(0,0) |

1 (14,3) |

4(20.0) |

19(133) |

0,672 |

|

girls and boys |

13 (46,4) |

58(65,2) |

1 (100,0) |

2(28,6) |

7(35,0) |

SI (56,2) |

|

|

NS NR |

10(35,7) |

22(24,7) |

0(0,0) |

4(57,1) |

9(45,0) |

44(30,6) |

|

|

Total |

28(100.0) |

89 (100.0) |

1 (100,0) |

7(100,0) |

20 (100,0) |

144 (100,0) |

|

|

Adequacy of knowledge to what is recommended (Analysis of the previous variable) |

|||||||

|

No |

5(27,8) |

8(12,1) |

0(0,0) |

1(33,3) |

5(41,7) |

19(19,0) |

0,142 |

|

Sim |

13(723) |

58(87,9) |

1 (100,0) |

2(66.7) |

7(58.3) |

81 (81,0) |

|

|

Total |

18 (100,0) |

66 (100,0) |

1 (100,0) |

3(100,0) |

12 (100,0) |

100 (100,0) |

|

|

Knowledge about the Purpose of the HPV Vaccine |

|||||||

|

No |

6(21,4) |

10(113) |

0(0,0) |

4(57,1) |

3(15,8) |

23(15,8) |

0,064 |

|

Sun |

22(78,6) |

79(S8,8) |

1 (100,0) |

3(42,9) |

16(S0,0) |

121 (843) |

|

|

Total |

28 (100.0) |

89 (100.0) |

1 (100,0) |

7(100.0) |

19 (100.0) |

144 (100,0) |

|

|

Adequacy of knowledge to what is recommended (Analysis of the previous variable) |

|||||||

|

No |

1 (4,5) |

2(2,3) |

0(0,0) |

0(0.0) |

1 (6,3) |

4(3,3) |

0,793 |

|

Sun |

21 (65,5) |

77(97,5) |

1 (100,0) |

3(100,0) |

15(93,7) |

117(96,7) |

|

|

Total |

22 (100,0) |

79 (100,0) |

1 (100,0) |

3 (100,0) |

16 (100,0) |

121 (100,0) |

|

Table 3 Distribution of patients with CCL attended at the IMIP according to variables related to knowledge about HPV, stratified by mesoregion, Pernambuco, 2016-2019

About the influence that the diagnosis of the oncological disease exerted on close family members (mother, daughters, granddaughters, nieces and sisters), the participants were asked questions related to the preventive examination and vaccination against HPV (Table 4). Among the interviewees, 132 (81.5%) have family members over the age of 25, and they report that most family members, 105 (79.5%), undergo an examination. The number of interviewees was high, 101 (76.3%), who associated their diagnosis with the search for family members to undergo the exam, and this percentage differs with statistical significance (p=0.007) in the São Francisco mesoregions, 1 (33, 3%) and the forest zone, 10 (52.6%).

|

Questions |

Agreste |

Metropolitana |

Sao Francisco |

Sertao |

Zona da Mata |

Total |

p-value |

|

n(H) |

n(%) |

n(%) |

n(H) |

n(H) |

n (%) |

||

|

Women in the family over 25 years old |

|||||||

|

No |

7 (20,0) |

IS (19,0) |

0(0,0) |

2(28,6) |

3(13,6) |

30(18,5) |

0,641 |

|

Sim |

28 (S0.0) |

77(81,0) |

3 (100,0) |

5(71,4) |

19(86,4) |

132(81,5) |

|

|

Total |

35 (100,0) |

95 (100,0) |

3 (100.0) |

7(100,0) |

22 (100,0) |

162 (100,0) |

|

|

Carrying out the preventive examination by women in the family over 25 years old |

|||||||

|

Nao |

8(28,6) |

5(6,5) |

0(0,0) |

1 (20.0) |

8(42.1) |

22(16.7) |

0,004 |

|

NSNR” |

0(0.0) |

5 (6.5) |

0(0,0) |

0(0,0) |

0(0.0) |

5(3,8) |

|

|

Sim |

20(71,4) |

67(87.0) |

3 (100,0) |

4 (S0.0) |

11(57,9) |

105(79,5) |

|

|

Total |

28 (100,0) |

77(100.0) |

3 (100.0) |

5(100,0) |

19 (100.0) |

132 (100,0) |

|

|

Influence of the CCL diagnosis on the search for carrying out the preventive in the women of the family |

|||||||

|

Nfo |

S(2S,6) |

8(10,4) |

1(33,3) |

1(20,0) |

9(47,4) |

27 (20.6) |

0,007 |

|

NSNR |

0(0,0) |

3(3,9) |

1 (33,3) |

0(0,0) |

0(0,0) |

4(3,1) |

|

|

Sim |

20(71,4) |

66 (85,7) |

1 (33,3) |

4(80,0) |

10(52,6) |

101 (76,3) |

|

|

Total |

28 (100.0) |

77(100,0) |

3 (100.0) |

5(100,0) |

19 (100,0) |

132 (100,0) |

|

|

Girls in the family between 9 and 21 years old |

|||||||

|

Nao |

11(31,4) |

30(31,6) |

2(66.7) |

1 (14,3) |

6(27,3) |

50(30,9) |

0,324 |

|

NSNR |

2(5,7) |

0(0,0) |

0(0.0) |

0(0,0) |

0(0.0) |

2(13) |

|

|

Sim |

22(62,9) |

65 (6S,4) |

1(33.3) |

6(85,7) |

16(72,7) |

110(67,9) |

|

|

Total |

35 (100,0) |

95 (100,0) |

3 (100.0) |

7(100,0) |

22 (100.0) |

162 (100,0) |

|

|

Girls in the family urged to get the HPV vaccine |

|||||||

|

Nao |

0(0,0) |

3(4,6) |

0(0,0) |

1 (16,7) |

1(63) |

5(4,5) |

0,049’ |

|

NSNR’ |

7(31,8) |

8(12,3) |

1(100,0) |

0(0,0) |

4(25,0) |

20(183) |

|

|

Sim |

15 (683) |

54(83,1) |

0 (0,0) |

5 (83,3) |

H (68,8) |

85(77,3) |

|

|

Total |

22 (100.0) |

65 (100,0) |

1 (100.0) |

6 (100,0) |

16 (100,0) |

110(100,0) |

|

|

Source of vaccine information |

|||||||

|

School |

5(33,3) |

16(29,6) |

2(0,0) |

0(50,0) |

3(27,3) |

26(30,6) |

0.SS6 |

|

health care professional |

13(86,7) |

47(87,0) |

3(0,0) |

1(75,0) |

9(81,8) |

73(85,9) |

0,876 |

|

telension |

1(6.7) |

5(93) |

1 (0.0) |

0(25,0) |

0(0.0) |

7(83) |

0,401 |

|

INQP |

1(6.7) |

0(0,0) |

0(0.0) |

0(0,0) |

0(0.0) |

1 (13) |

0,328 |

|

Pediatrician |

0(0,0) |

1(1.8) |

0(0.0) |

0(0,0) |

0(0,0) |

1(13) |

0,819 |

|

Total |

15(100.0) |

54(100.0) |

4(0.0) |

1(100.0) |

11(100.0) |

85(100,0) |

|

Table 4 Distribution of patients with CCL seen at the IMIP according to variables related to women in the family, stratified by mesoreetao, Pernambuco, 2016-2019

Still in this perspective, 110 (67.9%) women said they had family members aged between 09 and 21 years. The interviewees point out that: 75 (62.2%) family members received the HPV vaccine and 83 (82.2%) recognized the interference of their diagnosis in the family's search for the HPV vaccine.

Cancer prevails as an important public health problem in the world and is already among the four main causes of premature death (before 70 years of age) in most countries. Despite a process of transition of cancer types in developing nations (corresponding to the drop in neoplasms associated with infections), linked to socioeconomic risk factors for the development of the disease,1 cervical cancer (CCU) is still present. as the second most common among women in emerging countries,15 a fact that makes monitoring and evaluation of the control of this condition essential.

In national terms, recent studies indicate that the occurrence and mortality rates estimated in Brazil present intermediate values in relation to developing countries, but they are high when compared to developed countries with well-structured early detection programs. CCU is also the second most incident and the third cause of mortality in the Northeast region1.

Pernambuco comprises 05 mesoregions and, in terms of health regionalization, 12 GERES.16 In this study, when analyzing the sociodemographic profile of women with CCU stratified from the municipalities grouped by mesoregions, the results presented here showed similar trends, but with a deepening of some social inequalities between the mesoregions.

Cervical cancer is usually not frequent until the age of 30 years,17 as for it to develop in women with normal immune systems, chronic HPV infection must last for about 15 to 20 years,18 showing the peak of incidence in age group from 45 to 50 years.17 Therefore, the mean age of 49 years of the women in the sample corroborates the most frequently affected age group according to the literature. Studies relate low education and difficult access to health services and preventive exams as important factors related to late diagnosis of CC.14,19-21 The epidemiological profile of the patients in the sample is compatible with what prevails in studies when it comes to CC: lower education level, non-white race, and married/consensual marital status.18,22,23

Education is indicated as a sociodemographic factor strongly associated with the development of cytopathological alterations, for not carrying out the cytopathological examination22,24 and is still considered a poor prognostic factor.18 In 2017, in the state of Paraná, having low education was a determining factor associated with four times more chances of women being affected by high-grade injuries when belonging to this group.22 It is also worth highlighting the results of this study, indicating that, in Pernambuco, in the rural and backlands mesoregions, women had less education.

A research that analyzed mortality from CC in women living in the city of Recife showed that most deaths from this cause occurred in black women. These results indicate that socioeconomic factors contribute to the higher incidence of the disease in this race/color25 and are similar to the findings of this study. With the exception of skin cancer, CC is the one with the greatest potential for prevention and cure, and, when diagnosed early, women have a survival rate of approximately 70%. For early detection, the main strategy of CC screening programs is the Pap smear. In Brazil, this test is recommended for women aged 25 to 64 who have started sexual activity. The interval between exams must be three years, after two negative exams, with an annual interval.5,26 It is observed in this study that 88.9% of women report having knowledge about the preventive examination. As for the frequency of annual examination, it was reported by 60.9%, 54.9% in a time interval of up to three years and 29% did not undergo the examination prior to diagnosis.

With regard to knowledge about preventive examination and its importance, studies highlight that the lack of access to knowledge about the disease and about the methods of prevention increase the probability of occurrence of CCU.27,28 In this direction, in order to assess the knowledge, attitude and practice of women about the preventive examination for cervical cancer, a study carried out in Recife, in 2015, estimated that 99.6% of women had heard about the examination in terms of knowledge, 73.8% knew that it was to prevent CCU, and 62.7% stated that the exam should be done annually. Regarding practice, 94.6% adhere to the exam, 67.4% do it annually and 87% in an interval not exceeding three years.29

As for the reasons for non-adherence to the preventive exam prior to diagnosis, the lack of information about the need for the exam was the most prevalent justification in this study, followed by fear or embarrassment. In this sense, aiming to characterize the factors that influence women not having Pap smears, in Rio Grande do Norte, a survey indicated fear/shame as the main factor that interferes with the examination, reported by 60% of patients, while, comparatively, in this study, it represents the second cause (34%).30

The analysis of the variable beginning of the preventive examination shows that most women are in the age group <25 years. It can also be affirmed that increasing age is associated with a decrease in exam performance. A similar result was found in a study carried out in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, which showed an increase in the number of exams performed from the age group of 15 to 24 years old, as well as a gradual decrease in the number of exams from the age group of 50 years.31

It is assumed in the study that measuring the population's level of knowledge about HPV is important, as it allows, via the results obtained, to evaluate and select the appropriate strategies so that effective plans are built with promotion, prevention and early diagnosis measures changes caused by the virus.32 Thus, the variables related to women's knowledge show that 44.4% do not correlate HPV with CCU, however 84.2% claim to know the purpose of the HPV vaccine and recognize the health center as the main source of information, followed by television.

When analyzing knowledge about HPV and vaccines, a study conducted with users of five basic health units and two polyclinics in Campinas, São Paulo, found a similar result, in which almost 40.0% of respondents reported having heard about HPV, however, the main source of information was the media (41.7%).33 Also prevailed, the perception of women regarding the interference of their disease in the search of family members for preventive examination and immunization against HPV. During the data collection process, it was noticed that, when asked about the impact that CC had on their family members, the women reported that the disease became a triggering factor for greater care in terms of preventing this neoplasm.

Based on the above, the study findings point to the need to reinforce the importance of health education aimed at preventive examination, in particular, reinforcing actions aimed at women in the screening age group, and at the immunization against HPV of the public-target. It is necessary to consider the diversities between the mesoregions, which present a reality of inequality and inequality that pose challenges to CCU control programs, a disease that should be understood not only as an oncological indicator, but essentially as an indicator of social vulnerability and needs of health care. Given the relevance of the theme, it is suggested that further studies be carried out to deepen the theme.

None.

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

©2021 Araújo, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.