eISSN: 2576-4470

Review Article Volume 2 Issue 3

Department of Ethnography and Cultural Anthropology, University of Pecs, Hungary

Correspondence: Laszlo Koppany Csaji, Department of Ethnography and Cultural Anthropology, University of Pecs, Hungary , Tel 36705538276

Received: January 01, 2017 | Published: May 11, 2018

Citation: Csáji LK. How to become fundamentalist a hungarian charismatic prophet’s new religious movement in the carpathian basin (an anthropological discourse analysis). Sociol Int J. 2018;2(3):160-169. DOI: 10.15406/sij.2018.02.00043

This paper is an anthropological discourse analysis of a contemporary vernacular prophet's new religious movement, based on a seven years long anthropological fieldwork in Romania, Hungary, Slovakia and Serbia. The author gives an insight to the process how someone can become a member of this Christian fundamentalist group (the "shines").

“I have visited Heaven several times. I was also in Hell two times. I saw how things were going on there. The Holy Spirit took me there. I understood that the border between the dimensions of Heaven and Earth can be crossed, as the world is one. We can let heavenly felicity and heavenly powers into ourselves. Let’s open our souls and minds to God! The Holy Spirit can be involved into our lives. No one can imagine the happiness when someone receives the Holy Spirit!” 1– this narrative and its many variants can be heard from a contemporary folk prophet (“Prophet Dénes”2) and his fellows in the Carpathian basin. This fundamentalist new religious movement (NRM) has spread through Serbia, Romania, Hungary, Slovakia and Austria since 2008, and it preaches sermons about a perfect, direct connection to the Holy Spirit, necessary for a better human and natural environment and for saving ourselves from evil. Utopia – a perfect world without sins and sorrow, in which people live in harmony with each other and the universe or God – has been imagined and outlined in many ways. Can peace, love and harmony be a real objective of humankind? What else could be? My paper is about a Christian fundamentalist utopian vision, expressed and preached by a contemporary Hungarian folk prophet from Romania. This version of Utopia is based on a laic interpretation of the New Testament, and the members of the NRM focus on their direct and intensive connection with the Holy Spirit.

Prophet Dénes often speaks about his spiritual journeys, when he is led by the Holy Spirit to Heaven, Hell and a distant planet. He also explains the many shapes and kinds of angels. He stresses that it is possible to create a perfect life of our own. This Utopia is only partially similar to the teleological concepts of the New Jerusalem or Last Judgement, and the movement3 is far from being millenarian,4 and I will explain why it cannot be classified as Pentecostal, too. According to the prophet, the perfect world should be achieved in the members’ personal lifeworlds first, and later across the whole world. What are the main attitudes in this contemporary NRM towards Utopia? Are there doubts, disputes and quarrels among the members? What are the relevant and the rejected elements from the visions of Prophet Dénes? This paper is a discourse analysis focusing on the participants’ responses to Dénes’ utopian revelations, showing the wide range of reactions from active and positive reception to active and negative answers. This heterogeneity shows that some elements of a Utopia can even be divisive, causing conflicts and secessions within a group. What are the cultural patterns and the strategies to keep a group coherent? How can vernacular religiosity2 be constructed in a way that brings the meanings of certain terms closer to each other,5 as approximation and overlapping of vernacular semantic frames.3 In this paper I outline a cognitive process similar to Robert Glenn Howard’s4 term vernacular authority phenomenon:4 how to prevent quarrels and establish a more or less common register of knowledge in a group.5,6 This paper is not only a case study. It includes some theoretical approaches as well, to show how Michel Foucault’s “genealogic” way of discourse analysis7 can be developed into an anthropological method. Social sciences prefer the “from above” approach to discourse analysis,7–12 but anthropological observation gives a chance to study the discourse not only in general, but in situ, “from below”, and contextualize it with other aspects (discourse spaces).

I conducted anthropological fieldwork among this NRM from October 2010 till January 2017. The genealogic way of discourse analysis requires a wide range of field notes: recording as many sequences of speech events as we can, counting the frequency of topics, reactions and behaviors. I recognized that the anthropological way of discourse analysis must extend the meaning of “discourse” to non-textual communications and also to passivity (silence, nonparticipation in an event, not hugging somebody etc.). The required methodological base for this kind of analysis is participant observation, which gives the researcher the opportunity to experience a similar socialization process as those outsiders who become known to the movement and start to participate. At first glance, many cultural patterns seem special, many narratives seem unique and the style of behavior seems exotic (for the outsider who encounters the group, and starts to participate). Then step by step our focus shifts from the exotic to the usual. This is how the discourse competences emerge,12 and a charismatic “master discourse” 13 penetrates the movement.6 We should be sensitive not only to unusual or extreme phenomena,7 but to the usual as well, seeking what is relevant. We observe the variations and frequencies of the narratives, and the wide range of reactions outlines the reality of the group’s discourse space. The meanings are learnt over the course of many common experiences and feedback, hearing similar narratives many times. It engraves them into the individual’s knowledge registers. As an anthropologist, I had to precisely follow all the occurrences of narratives, their variations and the reactions to them to estimate the diversity of the participants’ mentalities and to demonstrate what can be considered “relevant” (more or less “common”) in the group.

Basic facts about the NRM organized by prophet dénes

Prophet Dénes is a folk prophet8 from Transylvania. He was born and lives in Homoródkarácsonyfalva (Crăciunel), Romania. He says he was chosen to be a prophet before his birth and was taught by the Holy Spirit for 22 years before the status of “the 22nd prophet of the Heavenly Glory” was given to him in 2008. The Holy Spirit took him on out of body travels and other visionary (spiritual) journeys to Heaven, to Hell, and even to a distant planet, where he saw strange life forms similar to humans. He says he talked to Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary. He had very special visions about angels,9 archangels and guardian angels. He makes a distinction between the Heavenly spirits who have already had an incarnation on the Earth and those who have not. The latter are white, while the former have a grey tone. Prophet Dénes believes in reincarnation: anyone who has been cleansed of her or his sins in Heaven10 can choose to come back to the Earth in a new body. He says he remembers fragments of his former lives. In one of them he was there when Jesus resurrected Lazarus. Prophet Dénes says that he has only one mission: to ensure that Jesus Christ finds more faith among the people when he returns11 to Earth. But until then, he says, we can build the perfect Christian life in our own lifeworlds with the help of the heavenly powers (the Holy Spirit), and the border between Heaven and Earth can become penetrated. The main aim for the participant is to receive the Holy Spirit and open their mind for an intensive communication. This gives the aura of a Pentecostal Awakening12 to the group, but there are some important differences. The first is that the group is expressly not only ecumenical, but inter-religious: the prophet stresses that he does not want to establish a new religion (or a new church), and all of his disciples should stay in their former congregations besides participating in his NRM; so approximately two third of the movement is Roman Catholic (about half of them have a charismatic orientation); most of the rest are Calvinist.13 The prophet himself is Unitarian,14 and he regularly participates in the rituals of his Unitarian congregation in his home village. The second difference is that the charismas15 which can be given by the Holy Spirit do not contain glossolalia (speaking in tongues)16 and exorcism (both are absent in this group). The third difference is the lack of ecstasy.17 It means that, despite a kind of trance state reached in common events, believers prefer individual meditation techniques which can be realized through prayer. The movement is an elitist fundamentalist one. Prophet Dénes stresses that to build a better world it is necessary to come back to the original, first Christians’ attitudes and values: to follow only Christ, not religious doctrines (and not even the prophet). Those in the movement all stress self-determination as an individual way of understanding God. They share their experiences and emotions within the group as a ritual deliberation within a shared ideological frame; personal responsibility for one’s own relationship with God gives a very individual frame for interpretations and creates a kind of vernacular authority, similar to some online movements.4 Prophet Dénes says there are many Holy Spirits (like helping spirits), some of whom are former humans that serve as incarnations of Heavenly Powers for this mission.18 He reports that in the Heaven there are no shadows, as light shines from inside the individual. That is why the core members of the movement call themselves “Shines”–those who have already “received the Holy Spirit”–referring to the Heavenly state, who obey the orders of the Holy Spirit, and illuminate the divine truth.

The prophet spends most of his time traveling: on foot and by motor scooter. He sleeps in a small tent. He tries to evangelize anybody he meets. He speaks Hungarian and Romanian, so his mission leads him to Romanian, Hungarian and Roma communities. When he is invited in, he reads small sections from the New Testament,19 blesses the audience, sometimes heals people and prays together with them. Prophet Dénes shows his special status with easily visible signs: by wearing a white shirt and trousers, a headband, a necklace with the Cross, and his unique beard (“shaved as Father God’s face appeared to me,” he explains). He stresses–according his interpretation of the Bible–that those who have received the Holy Spirit should wear white and headband. According to a strict order from the Holy Spirit, Prophet Dénes must not ask for money. He needs a supply of food for himself and petrol for his scooter, so he accepts donations, as he has no other income, and he often stays some days as a guest at suppliants or fellow members when he travels. He lives a very simple and poor life. Members keep all of their property. It is quite hard to estimate the number of the members of the group. Can those who inquire, who only seek for truth by participating in this NRM’s and others’ events be counted as members? The Shines and Candidates20 are approximately 45-50 persons nowadays. There are approximately 50-60 women and men who are active seekers or inquirers.21 Fluctuations of membership are quite frequent. A bit more than a half are female. Most of the members are from rural, middle class backgrounds, and higher education is under-represented, as about 30% of the members have a post-secondary degree. To this list we can add 60-80 persons who rarely participate: supporters, friends, and donors. Many people left the movement after one or more active years, so the activity of the prophet is similar to slash-and-burn agriculture. Only a dozen followers still remain from the first year. In the first phase (2008-2009) the new religious movement was built around Prophet Dénes, with distant hubs connected only to the prophet. In the second phase (2010-2012), members developed a new, cross-country religious network in the Carpathian Basin with local hubs, especially in Serbia. The movement’s local networks were strengthened after members shared a common vision, the so called “Miracle in Temerin”22 (North Serbia) on 15/11/2010. From then the South and central part of the Carpathian basin became the core region with many local hubs. The current network of the society can be seen in Map 1.

This is very tolerant, pluralist movement, causing doctrinal vagueness. Most of the members do not think that Christianity is the only religion that can lead us towards God, though the prophet expresses that religions are not equal: he explains that “There is a line. Some churches are high above, some are under this line”. As an example, he usually mentions–according to the suggestions of the Holy Spirit–that Pentecostal Christianity23 is high above the line. The Catholic and Calvinist churches and the Buddhist church are all a bit above, but the followers of Krishna or the Jehovah’s Witnesses are below it, which means that the latter ones have many false ideas. Relative plurality appears not only in religious aspects. This NRM’s three main pillars are the seeking for direct communication with transcendent heavenly powers, an anti-ethnocentric attitude and an ecologically conscious way of life. Let us briefly summarize these ideas.

Direct connection to the transcendent

Although the most important step for conversion to “real” Christian faith is to have a direct connection with the Holy Spirit, the institution of churches and priests cannot help in this route.24 They want to turn back to the fundaments of Christianity, and the age of apostles seems to be a model for their network-like community. This direct connection, which is created by becoming full of the Holy Spirit, can be reached with the help of the prophet, who supervises the Candidates, who ask for his help in this initiation process. They accept that there is a chance to receive Holy Spirit alone, without the help of anyone, but it is a long, hard and risky process.

Anti-ethnocentric attitude

Although Prophet Dénes goes to Romanian and Roma communities, and the members who live in Serbia go to their Serbian and Roma neighbors to evangelize them, the group communicates in Hungarian. While the interactions are always in Hungarian within the group, practically only those who speak Hungarian can become participants.25 All the members have a Hungarian ethnic identity, but one slogan of the group is that “God created human beings, not nations!”, which means that national identity is subsidiary, and our humanity is most important. Notwithstanding this tolerant attitude, most of the members accept alternative answers on the pre-history of Hungarians, and they declare Huns and Scythians as their ancestors. It is very interesting that a very much anti-ethnocentric attitude can be observed inside the group, but in the participants’ own lifeworlds, more than half are local activists for their ethnic groups. Most of them live as ethnic minority members outside Hungary and are proud of their Hungarian identities. They feel responsible for saving their Hungarian language and culture. They have a far from internationalist attitude, but they want to behave tolerantly, with respect to all other peoples and cultures.26

Ecological consciousness

The prophet’s utopian vision is not only religious. He expresses the importance of the ecologically conscious way of life, which includes responsibility for saving Nature and the obligation to keep “our traditional way of agricultural heritage”. He often stresses that “in spite of Thujas, people should plant vegetables and fruits”, and the chemical disaster of industrial agriculture shall be immediately stopped. This sensibility is related to contemporary global discourses about our responsibility towards our natural environment.

Discourse spaces, personal discourse horizons and threshold narratives

Long-term participant observation gives researchers an opportunity to estimate the role of narratives about the utopian “perfect life”, by measuring the communicative responses of the participants. Let us analyze such reactions, which include active acceptance and passive refusals. Some of them are rarely mentioned ones; the group surrounds them with silence. Others often appear in speech events, and receive many positive feedbacks. I have chosen the following types of narratives for particular analysis, as relevant elements of this NRM’s Utopia:

3.1. Connection to the transcendent world: 3.1.1. wearing emblematic signs of their faith (white dress, headband, and the Cross – based on reference to the Bible’s fundamental interpretation);

3.1.2. visions of Heaven (and Hell); 3.1.3. glimpses of angels (and visions of their shapes); 3.1.4. the concept that Christian priests have no real connection with Holy Spirit; 3.1.5. the assertion of many Holy Spirits (as heavenly guides); 3.1.6. the doctrine of reincarnation.

3.2. The anti-ethnocentric attitude: 3.2.1. that Hungarian language and culture should be respected and saved without confrontation with other peoples; 3.2.2. the idea that God created humans, not nations; 3.2.3. the insistence that, despite religious pluralism, Hungarians should prefer Christianity (religions and churches are not equally perfect).

3.3. Ecological consciousness: 3.3.1. calls for saving the natural environment; and 3.3.2. abstinence (alcohol- and nicotine-free life); 3.3.3 the knowledge of traditional agriculture, and the rejection of industrial agriculture; 3.3.4. the preference for homemade organic products.

These doctrines (topics) are certainly not equally relevant in the movement, and not all of the above-mentioned narratives of the prophet’s revelations received common acceptance. They do not form a mutually accepted common knowledge register, but we can consider them something like accepted values and narratives linked to their imagined Utopia. The value-system of the movement is not built only on these narratives and regulations. I have selected them for the present paper, as it would be impossible to analyze all aspects.

Before the analysis I outline the communication practice of the group. Certainly not all of the participants’ communication is inside the group. They are not isolated.27 It is a network-like movement, where people communicate with each other mainly on the internet (Skype, Facebook, e-mail, file-sharing and video-sharing websites, etc.), and offline meetings are quite rare: there are smaller subgroups who meet more often (as they are neighbors, colleagues, relatives), but despite these local hubs the movement’s mass ritual events happen four or five times yearly. Such occasions last for one to five days. These events are the anniversaries of the “Miracle of Temenin” in November, pilgrimages in spring and summer (some of them last for five days, owing to walking distance), the Shines’ and Candidates’ yearly summer assembly, and between 2010 and 2012 there were common evangelization events with fire-walking rituals (which was practiced as a legitimation technique). Between these events the prophet, the Shines and the Candidates meet each other and some Inquirers in smaller groups, organized locally, sometimes ad hoc, according to particular circumstances. Online communication is much more active. The group’s inner discourse cannot be researched by following only the online or the offline communications.19 after the first years, when information access was not regulated with threshold narratives, one main reason for the fluctuation of members was that people shared info with each other without any limitation. This caused many misunderstanding and quarrels, as some narratives were too divisive. I recognized that a semi-conscious, semi-instinctual gradation started to evolve in the movement. After some years of evangelization, the prophet and the core members realized that some narratives can shock newcomers, because they are not ready to understand their meanings. Meanings are constructed in the group’s inner discourse space. They form a flexible frame of emotions, experiences and narratives related to some topics rather than mutually agreed-on definitions. Nowadays some narratives can be told to anyone, while others should be told only to those who have expressed their inquiring attitude, and some are told only to those who have asked the help of Prophet Dénes to receive the Holy Spirit. I call this gradation “threshold narratives”. To cross the threshold requires a decision on the part of the participant: an outsider who shows her or his inquiring attitude becomes a seeker/inquirer, and seekers become Candidates by announcing their intention to receive the Holy Spirit with the supervision of Prophet Dénes. After a very active period of the Candidate, the prophet declares that the Candidate is ready to receive the Holy Spirit and swear the oath. All these steps result in access to a wider range of information and narratives. Of course only some outsiders start to inquire, and only a few inquirers ask the prophet to supervise them in “receiving the Holy Spirit”. The process to reach the status of Shine can last for several years. After participating in the movement some become inactive, dubious or even hostile towards the movement, so the process of fluctuation in and out can also be seen in Figure 1, in which I demonstrate the system of thresholds, as steps for information access.

Every crossing of a threshold is an expressed decision of the actual participant – a decision to step further: showing sensibility (first threshold), asking the supervision of the prophet (second threshold) and the initiation to receive the Holy Spirit (third threshold). 3.1.1., 3.2.1. and 3.3.1., 3.3.2. from the above narratives can be told to outsiders, but 3.1.2., 3.2.2., 3.2.3., 3.3.3. and 3.3.4. are to be told only to the those who show inquiry. Narratives 3.1.3., 3.1.4., 3.1.5. and 3.1.6. should be told only to the Candidates. Of course this is not a strict, institutional gradation, and there are some occasions on when outsiders can access narratives that would otherwise be hidden to them. These occasions can be accidental (e.g. on an anniversary of the “Miracle of Temerin”, where long conversations happen between Inquirers, Candidates and Shines) or as a result of searching on the internet, asking questions, etc. There is no sanction for those who transfer information which would not have been told to them, but the prophet and the Shines often express a desire not to “shock” people with narratives they are not prepared to hear yet.

It is essential for a NRM to create a more or less overlapping register of narrative knowledge,5 and to draw the value preferences of members closer to each other, constructing common values. Pierre Bourdieu called this embedded practice, as a frame of knowledge, interpretation and behavior “habitus”,15 and considered it a dynamic register. The members’ habitus should not be too diverse. The process of getting them closer can be started with the thresholds (followed by the engraving techniques, common experiences, positive feedback etc.). Shines instinctually realized that they cannot let “anyone” in (outsiders must be filtered), but the filter should be smooth, so as not to shut everyone out. With the threshold narratives the group lets only those participants who expresses their positive emotions closer to the inner values and secrets. The group makes a selection with the threshold narratives in three steps. This gradation is also necessary for the new member to get used to the discourse inside, and they also form the steps of a kind of initiation. For cognitive engraving (constructing a narrative register for the community) and to be familiar with the group’s value-system and regulations, it is necessary to establish a quasi-educational process, which directs the participants (Inquirers, Candidates) focus from the extreme and strange to the usual and relevant. The learning process includes not only engraving narrative knowledge but learning behavior models, getting used to them, creating more or less similar value-preferences, and bringing the attitudes of members closer to each other. Cognitive semantics uses the term “semantic frame” There is a higher chance for the participants who cross the thresholds to be ready for further initiation than for those without it. It is required to show susceptibility. In the innermost discourse space, shines have a register of narratives which contains some narratives that are open to the public and others that not. The gradation of threshold narratives seems to be a useful tool to protect this knowledge.

Besides the active communication in the NRM, all participants keep their personal “discourse horizons”. Certainly all of the participants have lives apart from the group: among their friends, at their jobs, with their relatives, in school, in political associations, at local events etc. Even their former congregation can be kept as an alternative religious discourse space. Discourse horizons consist of the personal lifeworld’s several discourse spaces, as long lasting or ad hoc interpretive communities.26 Some topics are nearly never discussed in the group (e.g. jobs, quarrels with relatives, sexual habits etc.). There are topics which are rarely mentioned (e.g. narrative 3.1.6., 3.2.2. and 3.2.3.) and there are some which can be considered core narratives (e.g. 3.1.3. and 3.3.1.). The following part of my paper contains a comparative analysis of these narratives to unravel the frequency and the range of reactions and to outline the participants’ responses to the revelation of Prophet Dénes.

4Even if the basic concepts of apocalyptic movements in the current online world can be similar(Hubbes, 2010).1

8He is not the first folk prophet in the Carpathian basin and in the Balkan region. In the last centuries there were dozens of prophets, prophetesses and “saint men” (and women) we know about (Valtchinova,16 Küllős-Sándor,17 Bálint,18 but to observe a “living” folk prophet can give us the chance to study the phenomenon in person (Csáji19)

9Rectangular forms with moving flounces around all four corners.

10He explains the cleaning process as a fog-like bath for the souls in the Heaven, where the souls slowly rise higher and higher depending on the weight of their sins and the prayers for them by their living loved ones.

11He stresses that no one knows the exact time, so he does not sermonize about the End Times; the millenarian expectation is one of the reasons he refuses the Jehova’s Witnesses, saying that they do not have a real connection with the Holy Spirit, otherwise they would have not made so many false prophecies about the Last Judgement.

13Some Buddhists and esoteric New Age activists also occasionally appear in ritual events.

Although Unitarians do not believe in Holy Trinity, they have very strong links to Calvinist church in the Carpathian basin in the last 450 years, so they identify themselves amongst the “original” Protestantism. Most Calvinists also classify themselves so in Transylvania (Csáji19).

15The most important charismas are: healing, prophesying (personal advice for outsiders and participants), blessing, foretelling and evangelization. Healing and evangelizing is very common charisma among the many “holy men/women” (Sávai–Grynaeus,21 Bálint18) in the Carpathian basin, but they should be distinguished from folk prophets, since they do not act as the chosen messengers of God, like prophets do.

17Comp. Hollenweger,20 218.

18This idea does not meet the concept of the Holy Spirit in his Unitarian congregation. This concept may be rooted in a shamanistic worldview, which has a revival not only in Hungary (Sávai–Grynaeus,21 Pócs,23 Küllős–Sándor,17 Peti24), but in many other countries, too. There is no evidence how the prophet received (or invented) this idea, since he states it is his own experience. The community of the Shines has no other Unitarian member, but the prophet himself.

19Only the New Testament is relevant to this movement. They not even read the Old Testament. The reason is that, according to the prophet’s interpretation, the Old Testament is fulfilled by the new one, so its role is at an end.

20Candidate (“kérő”) is the person who requested the supervision of the Prophet in the path to receive the Holy Spirit.

21Seeker (‘kereső’/’útkereső’) is an émic term for those who are searching for the “right way” of life, trying to understand several religions, joining and leaving groups, but have not found the optimal one. This can be compared to the overlapping émic category of Inquirers (“érdeklődő”), who are those who expressed their positive emotions towards the Prophet and/or the group, but has not requested the supervision of the Prophet yet.

22The praying audience had a vision: they saw a rainbow-colored dove-like form, which was transformed into a shining cross above the head of the prophet. It happened on November 15th, 2010, in Temerin, and the host house became a shrine since then. This became the most important reference of legitimation for the group.

23 He has good connections with many Pentecostal congregations, but the members of the movement refuse to identify themselves as Pentecostal, since they all keep their primary (official) religious identity. This shifts our focus towards the heterogeneous and ecumenical Charismatic Christianity.

24According to Prophet Dénes, “If a priest wears glasses, I always ask: what connection can he have with the Holy Spirit? If he had a direct connection, he could have asked the Holy Spirit to heal him… ’Ask, and it will be given,’ it is told in the Bible. But as his eyes are sick, it means he cannot ask for such help. He has no connection with the Holy Spirit. The priests have chosen the comfortable way, not God’s way.”

25This role of language is only a pragmatic consideration and not a norm at all. Members also use Serbian, Romanian or other languages in their personal evangelization activity, but members from Serbia do not speak Romanian, members from Romania do not speak Serbian, and neither of these languages are spoken by members from Hungary–so the only lingua franca is the Hungarian language for those who actually participate in the ritual events.

Frequency of discourse contents

The movement is based on the idea that those who seek direct connections with the transcendent world cannot receive the Holy Spirit with the help of their traditional congregation’s priests. This direct connection can be reached with a fundamental interpretation of the Bible, individually-developed praying practices and with the help of Prophet Dénes. They also tend to be ecologically conscious and hold tolerant attitudes towards their ethnic identity,28 contrary to the deeply ethno-politicized Carpathian Basin.

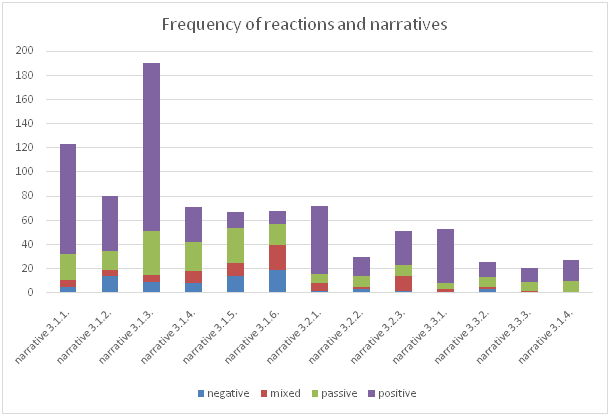

The chosen doctrines of 3.1.1.-3.3.4 can be analyzed in many ways. One useful tool for a study can be sequence estimation. This can frame a mixture of quantitative and qualitative methods. In Figure 2 the difference of frequencies between some narratives blocks, which all contain many variants and simple mentions, are easily recognized. A reincarnation narrative appeared on fewer than 70 occasions (68) altogether in my five-year observation between 2011 and 2015. Glimpses of angels and other visions of angels form a huge part of the total discourse, as they had nearly two hundred (cca. 190) mentions. Abstinence, traditional agriculture and organic food29 supply had altogether 70 mentions in speech events, which suggests they are less relevant (but with a high rate of acceptance). In this group active negative reactions occur very rarely. The much more usual way to resist a narrative is to stay silent (without comments or questions).

Figure 2 Frequency of reactions to some narratives related to utopia (inquirers, supporters, candidates and shines are considered and counted together) between 2011–2015.

Figure 3 demonstrates the thirteen types of narratives chosen for this analysis. I counted all appearances I observed during fieldwork and recognized in my field-notes and field records. I recorded the number of related speech events I witnessed. Then I created four categories according to the attitude of the actors: whether the topic received positive, negative, passive or mixed feedback. These categories form the levels of the columns, and the columns’ heights show the number of speech events altogether. This categorization sheds light on some methodological problems of such a measurement. All models that transform human behavior, emotion or knowledge into statistical matrixes are certainly simplifications. The summarizing diagram (Figure 2) gives only a basic overview of the frequency of the analyzed narratives. As I have mentioned before, discourse contains not only narratives, but emotions, reminiscences, behaviors like silence or passive resistance, etc. Doctrine 3.1.1. (Dressing codes and wearing symbols) is an important expression of their religious identity, but something which rarely requires verbal expression. How should I count its appearance and relevance? All the appearances of a member show the acceptance of this dress pattern and show a symbolic code to those who understand the symbols of the Cross, the circle, and the oval form with many rays. This fact also stresses the relative importance of textual expressions. But other forms of behavior can hardly be transformed into quantitative data that provides comparable numbers.

Even the verbal expressions are hard to transform into comparable numbers, as sometimes only two participants speak to each other and on other occasions many members and outsiders meet, but sometimes only a few members are actively involved in the conversation. How could I estimate passive or totally silent reactions? In a ritual event I experienced a situation in which two members started to talk about reincarnation with very positive attitudes, as they accepted this doctrine. There were seven other persons in the group who heard them, as they were all part of the conversation until this topic arose. At this stage all others stayed silent, and I thought two or three of them looked skeptical. These ones started to talk to each other about a neutral topic (when they should wake up the next morning for the long walk for a pilgrimage). Others who stood around slowly moved towards those who were talking about practical and neutral matters, and after some minutes there were two separate conversations: between the two who were talking about reincarnation and between the seven who were talking about the next morning. No critical opinion was expressed, and no impolite behavior was seen, as the two started to talk quietly in their private sphere and others just joined them.

Another difficulty of the estimation is the heterogeneity and the ambivalence of the reactions. When a dispute arises, the attitudes can vary widely and opinions can be changed. For example, the doctrine numbered 3.2.2. was once heard after a joke which stereotypically mocks Roma people (gypsies) and parodies the perceived image of Roma as thieves: “Policemen are cooking a Gypsy man on a skewer over a fire. A policeman turns him. The other policemen come back and ask their colleague why he turns the Gypsy so fast. He replies that when he turned slowly, the Gypsy started to steal the potatoes and tomatoes from beside the fireplace.” After the laugh, some of the audience stayed silent, and later, when prophet Dénes started speaking, he said, “We can learn something from everybody. From the Gypsies we can also learn much, such as how to value our parents and family, and furthermore that they have so many children.” Participants replied positively. Most of the movement’s shines support the evangelization to the “Gipsy streets at the end of the village”–but in the background of this activity we can recognize a form of a hierarchic concept: they believe this would include rising up those from our society who live in sin and against the law. They expressly refuse ethnocentrism, but they joke about ethnicity, make ethnic oppositions such as “Hungarians have turned away from the Bible”, or “from the values of the family”, unlike e.g. the Bunjevci.30

Some topics are usually discussed in face-to-face situations, e-mails, or Skype conversations (like personal dreams, visions about each other), while others are public themes (e.g. new information about ecologically conscious farms, which are ready to supply those who desire organic food). Reactions can be very variable: not only positive, negative and passive. Any narrative can catalyze (call out) a wide range of emotions, memories, experiences, unconscious reactions, associations, behavior patterns and connected narratives. Everyone has more or less different sets of potentially activated knowledge and emotions. How could we count and compare them? This can be an obstacle not only to numeric transformation but also to the endeavor of comparing human emotions and knowledge in social and cultural studies.

I argue that quantitative studies have limited relevance in anthropological studies, but can create a database that serves as a helpful tool for more adequate qualitative analysis. Realizing these above-mentioned difficulties, I consider the Figure 2 estimation, a relative database, not as quantitative evidence. Categories contain negative, mixed (positive and negative), passive (unrecognizable or simply silent) and positive reactions as a sematic frame of meanings, emotions and feedbacks. I focused on the reactions of the audience when a narrative of the analyzed doctrines (one or more from the thirteen, described in 3.1.1–3.3.4.) appeared. Numbers represent related speech events, not the number of occasions when the narratives were mentioned in them31 Figure 2. clearly shows the difference between the often-mentioned (3.1.3. and 3.1.1.) and the rarely-mentioned topics (3.2.2. and 3.3.3.), and also illustrates which are the divisive narratives (e.g. 3.1.4–3.1.6. or 3.3.2.) Figure 2. Summarizes the data of a five-year-long participant observation, so it is not a dynamic model. I will show a time-scaled (dynamic) analysis later, according to the 3.1.4 and 3.1.5. narratives in Figure 3 & Figure 4.

Discourse analysis of a conflict

Anthropological discourse analysis should both consider the time dimension and the frequency of behaviors. The sequence of signs and enouncements (énoncés) is per definitionem emerging in time25 and in particular situations. The main question is how the religious movement constructs itself by its discourses and what kind of inner interpretative communities can be perceived. In this part of my paper I will focus on a particular dispute which was happened in 2014. The dispute had serious consequences. One of the basic statements of discourse theory is that topics are not given and meanings are much more than simple definitions, they are continuously formed by the discourse itself.7 Cognitive semantics adds that meanings are individual and form a frame of more or less overlapping, potentially activated knowledge: interpretations, emotions and associations.14 Threshold narratives serve to overlap meanings and interpretations within a religious movement. Let us deconstruct this with a particular case study about a dispute. I have chosen two narratives for deeper analysis: 3.1.5., about the many Holy Spirits, and 3.1.6., about reincarnation. These selected narratives were important topics during the dispute.

A Catholic Charismatic prayer group joined the movement of Prophet Dénes in 2009, and they became among the most active members. They participated in as many events as they could, and the “Miracle of Temerin” in 2010 happened in a house belonging to a married couple from this subgroup. All but one of the witnesses of the miracle was members of this prayer group. The house started to become a symbolic center of the movement and a place of pilgrimage.32 They felt that they became the core group of the movement and organized several ritual assemblies. Narrative 3.1.5. and 3.1.6. were very rarely mentioned in 2010-2013, as these doctrines were hard for this group to understand, given their Catholic backgrounds. Some personal interpretations emerged about narrative 3.1.5. from 2010-2013, but narrative 3.1.6. was nearly neglected. To the question “how could we imagine that there are several Holy Spirits?” participants gave answers like:

Unlike other religious matters, participants nearly never discussed this theme (narrative 3.1.6.) with each-other, because they could not give an answer which would have been compatible with their existing religious image. Narrative 3.1.5. was also very rarely mentioned. After the first years, the movement neglected both, until something happened. A personal conflict between the leader of this prayer group and Prophet Dénes catalyzed the dispute at the very beginning of 2014. The conflict was based on a personal affair, and was mentioned only as gossip. It was never a public topic.

When the prayer group joined the movement in 2009, its leader was accepted by Prophet Dénes as someone who was already a “shine”. She received the Holy Spirit and was fulfilled with it. From this early time, there was another conflict waiting in the background in Temerin: the local Catholic congregation’s reaction to Prophet Dénes, especially the disapproval of the Catholic priest. As the members had double religious identity, a simultaneous relationship with their former congregation and the NRM as well, this conflict was managed for a time. Prophet Dénes told many times that in 2010 he once joined a Catholic mass in Tenerin, where the priest sermonized that “there is a man with beard among us who does not want the believers to go to churches and to trust in priests”. The prophet considered this accusation a total lie. This was an explicit attack against the group, but the 15-18 members of the actual Charismatic prayer group insisted on participating in both religious communities: in the local Catholic one and the network-like NRM as well. For three years a status quo seemed to be established between these two religious leaders. After the personal affair, the explicit conflict started with two dreams. One was dreamt by Prophet Dénes and the other by one of the core members, a woman who also lives in northern Serbia, but not in Temerin. The later told her dream to the prophet: that she saw the wooden cross which was placed on the roof of the living room in the “house of Miracle in Temerin” separated with furniture by the owners, like they wanted to hide it from their local neighbors and friends. Prophet Dénes also shared his dream about the leader of that prayer group. He also told about the personal affair. Prophet Dénes and his acolyte agreed that a problem was coming.

The prayer group leader and her husband also talked about their recent feelings and shared their emotions with the other participants in their prayer group. They said that in Temerin there is an accusation against those who belong to a “sect”. The local opinion certainly contained this interpretation as well, but most of the locals I talked to respected the owners of the house of “the Miracle”. The house was marked by two large religious flags and the owners did not care much about the minority opinions (and gossip) of their “sectarian” kind until then. They felt that their house became a site of pilgrimage. Their opinion was that the “sectarian accusation” can be addressed with active participation in their local Catholic congregation (besides their active role in the NRM of the prophet). The conflict did not receive common attention, and did not have a theoretical or theological aspect until May 2014, when the entire prayer group decided not to participate in the four-day Pentecostal walking pilgrimage to Csíksomlyó33 starting from the home village of the prophet. From January 2014, the prayer group, unlike the rest of the NRM, started to talk often about some theoretical topics (e.g. 3.1.5. and 3.1.6.) which were not relevant doctrines until then. Their opinions shifted from passive/positive to negative refusal. From the first half of 2014, these unusual (later considered extreme) narratives were discussed much more often than before. Narrative 3.1.5. and 3.1.6. were among them (as was 3.1.4.). The prayer group’s new interpretations related to these until-then irrelevant, rare topics. New reflections and negative emotions added new, negative meanings to them. Members of the prayer group started to express that the “sectarian” vision was based on these false ideas. The image of Many Holy Spirits and reincarnation started to be considered non-Christian, and even the word heresy was mentioned. This process lasted for not more than half a year. Parallel to this process, the rest of the NRM started to consider the prayer group as wanting to expropriate the “Miracle of Temerin”. They mentioned experiences that led them to believe that the members of the prayer group wanted to appropriate the shrine, so they would only “host” other members of the movement in the house of the miracle. They considered small signs evidence that the prayer group wanted to monopolize the holy places and especially anniversary rituals, that they “decided things without asking the not-from-Temerin members”. An inner border was created, creating a “we” and “they” opposition on both sides. Interpretative horizons were separated from each-other. The former “most active” subgroup started to be considered as a “renitent” one in the NRM.

Communication was active on both sides about the “other”. News and messages rarely reached the other side; interactions decreased. The prophet thought that time will solve the problem. Most of the doctrines were still accepted by the prayer group, but some of them were used as scandalizing doctrines. The Temerin subgroup gave ad hoc names to “the others” as “those who believe in reincarnation”, and to their own circle as “those who believe in one Holy Spirit”. There were other ruptures, e.g. the fire-walking ritual (practiced by the group from 2011).34 But the most relevant doctrines were not challenged, otherwise they would have denied their own former years, and the most relevant doctrines are not “extreme”, and are more or less compatible with their Catholic faith. The phatic communion28 was based in both groups on a very similar phatic communication style, using short sentences about glimpses of angels, phrases of the Holy Spirit, positive feedback about their honestly-spoken emotions towards God and so on. Legitimation techniques in both side were based on the Holy Spirit and the fundamental short references to or interpretations of the Bible.

In the summer of 2014, the NRM “officially” declared (members confessed to themselves) that the movement had been divided. Some messages appeared later directed at the “secessionists” e.g. on Facebook, saying “Where is your faith?” and so on, but in 2015 the dispute gave way to a more silent status quo. The prayer group did not talk much about the NRM and Prophet Dénes in 2015. It became rare to hear something about the “Temerinians” in the NRM. The prayer group considers the miraculous vision as something that “showed the power of the Holy Spirit over Prophet Dénes, and did not glorify him. Our attention moved from Dénes to the Holy Spirit, from failed interpretations to the divine truth.” That is why they do not hold anniversary celebrations any more.

The interpretive horizon split into two parts: the Temerin prayer group and the rest of the movement as parallel realities. Control over the discourse was cracked.11,12 Their interpretations went in different ways, which caused a shift of relevance: the Temerin prayer group paid more attention to some seemingly extreme and easy-to-criticize narratives. At the end of the dispute (in autumn 2014), the prophet declared that “The memorial place for the ‘Miracle of Temerin’ has been replaced, and the Holy Spirit suggested to place it in Topolya.” Topolya (Bačka Topola) is also a village in northern Serbia, but it is forty kilometers north of Temerin, and home to the most active core members. It was a later decision to keep the anniversaries in Temerin, in another house, but near the real one. Only one family from Temerin stayed in the movement,35 So this family offered its house for the anniversaries of the “Miracle of Temerin” from the year 2014. Their house is about 300 meters from the one where the miracle happened.

I show the time/frequency dynamic model of narratives 3.1.5. and 3.1.6. in Figure 3 & Figure 4. Below Of course these appearances are only those that I observed or recorded in online and offline communication. It is easily recognizable that the frequency and the changing of the prayer group’s attitude correlated in this conflict, and later the frequency of these narratives nearly disappeared among the prayer group of Temerin. For the rest of the movement, narrative 3.1.5. and 3.1.6. did not appear in verbal or written speech events more that before (they remained rarely mentioned).

We can clearly see that the Temerin subgroup is overrepresented in the appearances of narratives 3.1.5. and 3.1.6. in 2014, if we compare these appearances with all the members of the NRM, for whom these were less important matters. This can be easily demonstrated by Figure 3 & Figure 4, as they show the quick growth of frequency in 2014 (during the dispute), after which the mentions fall down to nearly zero. The dispute was salved with the secession, but the topic catalyzed deep emotions, so the prayer group of Temerin rarely mentioned it.36 The phenomena that different interpretative communities constructed opposite meanings of a common experience was similar to a Bulgarian NRM in the 1920s and 30s (“The Good Samaritanians”), organized around folk prophets (e.g. Bona Velinova, a prophetess). They also imagined a visionary “perfect world,” which they called New Jerusalem, but then the leader of them was accused of witchcraft by the local Orthodox Church.16

To help us understand the motivations and emotions activated by the appearances of a narrative, the actual situation and the actors’ personal backgrounds should be given. For example, the mention of the reincarnation narrative in the secession group happened in summer 2014 (the only one signifying a “mixed” attitude) in a conversation between two members, when one of them said, “I would like to believe in reincarnation. It would be so good! But I can’t.” The answer was, “God can manage everything. If God wishes so, anything, even this, could happen, but I don’t think in the way Dénes says.” And the conversation ended with the reply “Yes.” In this situation, “yes” signaled the closing of the topic, rather than an agreement. They did not totally agree, but they did not want to have a dispute.

After the secession, the conclusion for those who stayed in the NRM was that there are some narratives which are divisive, so most members wanted to hide them by ignoring or isolating them. Maybe even the prophet wanted to forget some. The written and performed things could not be changed, and nobody wanted to deny their past expressly.19 The experience caused a tendency to consolidate: to concentrate on less unusual messages. This helped the “threshold narrative” system to emerge in 2014-2015.

The threshold narrative system is not only an educational and selection technique, but also a strategy for hiding past shames and embarrassing narratives that would be better buried. Closing them into the “secret circles” of the group’s discourse space can also be a tool for dispute-preventive consolidation. The divisive narratives became part of the “third threshold narrative block” of the movement. Since then narrative 3.1.5. and 3.1.6. are very rarely mentioned in either group.

28Three-fourths of the members live in a territory where Hungarians form a minority (in Serbia and Romania).

29Nutrition can be sacralized not only among Christians; organic food has importance in most ecologically-conscious religious (and even New Age groups), like the followers of Krishna (see Farkas27); this can be compared to and divided from the wider context of a healthy way of life.

30The Bunjevci migrated from Herzegovina to the Alföld (Lowland) of the Carpathian Basin (and some of them to the Velebit Mountains in Croatia) in the 17th century. They speak a dialect of Croatian. In Serbia, Bunjevac is accepted as an ethnic unit and language. Most of them live in and around Subotica. Most of them are Catholics, and some are Protestants. Those in the movement consider them a very religious, hard-working people.

31Some speech events (conversations, Facebook uploads, YouTube comments etc.) contain a dozen mentions and others contain only a reference on an actual narrative.

32Similar phenomena could be witnessed in Szőkefalva (Seuca) in Romania, where a blind local woman’s visions of the Virgin Mary attracted attention, and a mass-pilgrimage place evolved in the last two decades (see Pócs,23 Peti24). Prophet Dénes went to meet that women and had a conversation with her.

33The pilgrimage’s goal was the Franciscan temple and statue of the Virgin Mary in Csíksomyló (Șumuleu Ciuc, East Transylvania, Romania). It has been one of the main pilgrimage destinations for Hungarians in the last 25 years.

34Many of the prayer group’s members participated in these ritual events before.

35They were not members of that prayer group, but the wife was witnessed the miracle. They have relatives and friends among this NRM in Topolya and Bácskossuthfalva (also in Serbia).

36Another considerable reason is that I focused on the movement in my participant observation, and I participated in much fewer speech events among the secessionist group.

This paper is an anthropological discourse analysis of a contemporary folk prophet's new religious movement, based on a seven years long anthropological fieldwork in Romania, Hungary, Slovakia and Serbia. I wanted to give an insight to the process how someone can become a member of this group (the "shines"), and the members classify themselves as Christian fundamentalists.37 I have conducted long-term anthropological fieldwork among a new religious movement in the Carpathian Basin from 2010, and in this paper I analyzed the discourses connected to the “perfect life” revelations of its leader, a Hungarian folk prophet (Prophet Dénes) from Transylvania (Romania). In the first part of the paper I explained the basic facts about the movement. It is ecumenical: its members keep the identity of their “inherited” congregations, and of course they built a new identity according to the revelations of Prophet Dénes and his most important acolytes. Then I demonstrated that a kind of gradation slowly developed in the group, which narratives catalyze decision-makings of the participants. I named them “threshold narratives”, stressing their divisive kind. Newcomers do not encounter all of the doctrines and narratives of the group. Outsiders should be told only the first threshold narratives, not to be frightened. Then, when some of them express a positive attitude towards these basic values and knowledge, they can step further and listen to the next block of threshold narratives. The next step is taken when someone from these Inquirers expresses her or his will to follow the supervising suggestions of Prophet Dénes and to obey the orders of the Holy Spirit. These Candidates can access the third threshold narratives. The prophet can at any time declare that a Candidate is ready to swear the oath and receive the Holy Spirit (to become a Shine). The limited access to knowledge is a useful tool for selecting the people susceptible to the secret narratives and values, and also for preparing them for these more extreme, more unique narratives. This process is a selection of the inquirers and a teaching method as well.

Then I analyzed some concrete narratives about the “perfect life”. I divided them into three categories:

These are the main topics of the participants’ interest, and I summarized the appearances of these narratives according to my five-year-long participant observation and online ethnography (Figure 2). I found that the symbolic signs of their religious identity (narrative 3.1.1. wearing white dress, the symbols of Father, Son and Holy Spirit); narrative 3.1.2. (visions of Heaven), and especially narrative 3.1.3. (Glimpses of angels and their visions) form the most often mentioned and most accepted narratives. In the last part of my paper I analyzed a conflict that happened in 2014. The personal conflict between the Temerin prayer group leader and Prophet Dénes was, in the beginning, a topic for gossip, but not for theological disputes. Then the communication inside the prayer group had been isolated, combined and new interpretations were constructed. These new interpretations did not affect the most relevant themes and doctrines, but selected some very rarely-mentioned and “extreme” ones: the fire-walking ritual of the NRM, the reincarnation theory and the concept of Holy Spirits as a plural person of God, etc. The movement was divided into two interpretive communities, and the prayer group of Temerin embraced newly-emerged meanings, which resulted in a confrontation. Even the concept of “heretic”, “sectarian” and “those who believe in reincarnation” appeared as an opposition to the rest of the movement. Parallel (opposing) realities started to be constructed in the dissevered discourse spaces of them. The personal knowledge registers, experiences, lifeworlds, emotions and ethnic, professional, local or other relations should be considered when individual discourse horizons and vernacular religion is researched. I demonstrated with a case study that the group’s interpretations and personal meanings never overlap each other perfectly, and actual situations can cause radical shifts of interpretations, which can result in secession or a conclusion of the movement in order to hide some kind of knowledge, and to create a more consistent discourse space. A semi-conscious, semi-instinctual “threshold narrative system” is a way to give a kind of order to the discourse, and to bring the personal interpretations closer to each other. This can also be a strategy by the NRM to hide those experiences and narratives that are too divisive to share by the NRM. So the conflict did not end without an effect: the NRM learned much about this problem and there emerged a selection-, education- and preventive-system: the gradation of “threshold narratives”. It does not take a yes/no decision to be a fundamentalist (or a member of a NRM), but a process of “small decisions”, by learning the special meanings as a reality-construction through the discourse of the fundamentalist new religious group.

37Even if most Christian theologians would refuse this term for them, and some judges them “heretic”.

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

©2018 Csáji. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.