Journal of

eISSN: 2573-2897

Opinion Volume 8 Issue 2

Antiquities Sector Saudi Ministry of Culture Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence: Majeed Khan, Antiquities Sector Saudi Ministry of Culture Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Received: June 05, 2023 | Published: July 3, 2023

Citation: Khan M, Al-Jabrin F. Exploring new rock art site of cow domestication in prehistoric Saudi Arabia. J His Arch & Anthropol Sci. 2023;8(2):69-71 DOI: 10.15406/jhaas.2023.08.00276

Saudi Arabia is not only rich in its oil but also stands fourth among the richest rock art regions of the world. Thousands of human and animal petroglyphs are located all over the country. The fauna and flora in the art represented various cultural phases as well as climatic changes. Cow is among the most prominent animals shown in almost all cultural period of the country but in different forms, size and styles. The art gallery recently located at Wadi Bajdha, Tabuk area bordering the recently developed most ultramodern and unique new city of Neon represented various phases of human presences in the area.

Keywords: wadi bajdha, tabuk, neom, art gallery, cows, camel and horse riders climatic change, thamudic inscriptions, beautiful location, rainwater collection area, panoramic locality

MB, Mitochondrial diseases; mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; GTCS, generalized tonic-clonic seizure; HSV, herpes simplex virus; ENMG, electroneuromyography

Saudi Arabia is a huge country spread in a large area of about 2 million square km. Rock art sites are located in almost all the country.1 Comprehensive rock art and inscription survey initiated in 1981 continued for over 15 years. 2000 rock art sites were documented recording thousands of Pre-Arabic and early Arabic inscriptions in addition to thousands of petroglyphs make Saudi Arabia the fourth riches rock art region in the world.1,2 In spite of these intensive and comprehensive investigations still some local and other official sources reported new sites unexplored by the previous teams. Example is the recently reported a huge rock art site located in Wadi Bajdha, northwest of Tabuk in a deep valley in mid desert.

The site is located in a remote area where water collected during the rainy season in a depression surrounded by mountains. It was and still is an impressive and panoramic area where people in the past should have lived or camped as a Bedouin tent still present in the area. The site also lies in the territory of the famous and world renowned (under development) city of Neom, hidden in the range of mountains that will certainly be part of the Neom tourism attraction.

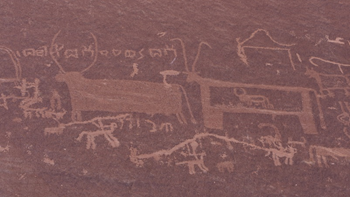

The art gallery is located on the vertical surface of a hill where people from time to time depicted images of their interest in different cultural periods. The oldest figures on this panel are that of cows with short horns and flat humps (Figure 1) suggesting cow of a different origin not like those located in the south (Najran area) with raised humped Indian Zebu (Figure 2) This is the second phase of cow origin and development in Arabia after the long-horned oxen located at the Neolithic sites of Jubbah and Shuwaymis (Figure 3) (Figure 4). Both Jubbah and Shuwaymis are now placed in the UNESCO‘s world heritage list.

Figure 2 An open air temple, cows are depicted with idoliform images possibly deities or gods located in Wadi Damm northwest of Tabuk. An evidence of cow worship in Arabia.

Figure 3 and Figure 4 Long horned flat back oxen Neolithic site Shuwaymis, north of the country. An evidence of the presence of wild ox in Arabia.

The rock art of Saudi Arabia shows a great diversity of meaning and purpose in different contexts and probably represents a multiple of functions. The cattle at Jubbah are found in different contexts from those represented at Khamasin, Najran and Tabuk. Diversity of purpose may be deduced from a Neolithic example of an ox, depicted both as a sacred animal and as a hunted animal. In the Chalcolithic, there is ample evidence of ox being a mythical animal, as a sacrificial animal, and as a deity. In such a diversity of representations, comparison and contrast with other sites have to be taken into account in order to reach secure conclusions regarding the interpretation of different panels. However, it is evident that a single or a standard meaning cannot be ascribed to any specific animal representation. The cow is mentioned 34 places in the Bible and 4 times in the Quran. It was a sacred animal in Arabia and In Egypt during the Pharaohs period. It is still a holy animal in the present Hindu mythology and is considered as a goddess and called Gao Matta or the Mother goddess.

According to archaeological and rock art evidence, wild cattle (Bos primigenius) was present in prehistoric Arabia both as a wild and domesticated animal. In the Neolithic rock art of Shuwaymis, Jubbah, Hanakiya and elsewhere exaggeratedly large horn and flat backed oxen are located in large number.3,4 These are apparently similar to Bos primigenis European type wild cows extinct long ago in Arabia and do not found after the change in climate in the Neolithic from cool and humid to hot and dry conditions (Figures 3–9).

Figure 5 Earliest image of long horned cow Bos primigenius, dated 9000 BCE, located at the Neolithic site of Jubbah, north of the country superimposed on it is a camel figure of much later period. There is a difference of several thousand years between the two animals; representing two climatic phases cool and humid (for cows) and hot and dry conditions good for camel.s

Figure 6 A pregnant cow. In this figure we can see a small baby inside the mother cow, a firm indication of a domesticated cow. Domesticated small horned and flat back cattle are found on several sites in northern and southern Arabia representing the middle phase of Chalcolithic domesticated cows 3500 BCE.

Figure 7 Indian humped Zabu appeared in Arabia after the Bronze Age 3500 years BCE when climate changed from cool and humid to hot and dry conditions. The long-horned wild ox disappeared from the peninsula and short honed humped cattle were probably brought to Arabia when environment changed from green grassland to hot and dry desert conditions.

Figure 8 The third phase in the art gallery represented by camel and pre-Arabic Thamudic inscriptions in addition to horse riders with long lances in fighting attitude drawn by the people representing the last phase of rock art in this gallery.

Figure 9 Dr, Faisal al Jabrin explaining the importance of rock art panel at Wadi Bajdha,Tabuk. Different artists in different cultural periods used the same rock and same space to add their figures but carefully avoiding superimpositions and overlapping the old cow figures. It shows a tendency to share their ancestor’s artwork and their heritage by preserving originality of their art.

Left corner of the panel contains images of a large cow, ibexes, horse riders depicted by different people at different times avoiding superimpositions and overlapping. Tribal symbols (E, +, P} represent most recent additions.

Cow petroglyphs in Arabia represented three climatic phases, in each phase the size, style and technique of execution is different and help us in developing chronology of animal type according to climatic change.

The rock gallery at Wadi Bajdha, Tabuk suggested that earliest residents of this area could possibly be attributed to the Chalcolithic period c.3500 BCE. They had domesticated cows and goats and perhaps small - scale farming depended mostly on ibex hunting. There were no camels in this period as I have suggested in my many several publications.3–5 Camel appeared in Arabia during early Bronze Age as well as the date palm trees. There are no camel figures in this art gallery. However, horse riders with long lances indicate tribal wars which was common among the Bedouin tribes until recent past.

This new site of Wadi Bajda is unique in the sense that it has no camel figures and cows are apparently domesticated with one shown with a baby inside the body. It was a good living place where people lived for short or long period and may have left due to change in climatic conditions from cool and humid to hot and dry conditions. Many large or small rock art sites in Saudi Arabia show the same pattern (Khan where hundreds of human and animal figures are located in a single area (such as Jubbah, Shuwayis, Hanakiya and Najran) but somehow abandoned immediately like our site of Wadi Bajdha.5–7 On these sites we do not see continuity of human presence for long time. Until recent past Saudi Arabia was a country of Bedouins who changed their camps according to the availability of water in the desert, Wadi Bajda site represented a typical prehistoric living style based on availability of water and better environmental conditions.8,9

None.

Author declares there are no conflicts of interests.

None.

©2023 Khan. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.