Journal of

eISSN: 2573-2897

Research Article Volume 9 Issue 1

Lecturer of Egyptology, Faculty of Archaeology, Damietta University, Egypt

Correspondence: Ahmed Abdelhafez, Lecturer of Egyptology, Faculty of Archaeology, Damietta University, Damietta, Egypt,

Received: March 11, 2024 | Published: April 8, 2024

Citation: Abdelhafez A. The social role of women in prehistoric Egypt: an analysis of female figurines and iconography. J His Arch & Anthropol Sci. 2024;9(1):62-68 DOI: 10.15406/jhaas.2024.09.00299

Female figurines from most periods of ancient Egyptian history occur in a variety of contexts. These images were often fashioned from clay, faience, ivory, stone, and wood. Of these, female figurines discovered in funerary contexts are highly interesting: Did they represent family members of the deceased, or was it a sort of ritual that entailed placing a feminine model with deceased males to serve them in the afterlife? In this paper, I will primarily analyze the social role of women in prehistoric Egypt. Additionally, I will also assess artistic renditions and the overall iconography of feminine figurines from that period. The following questions will help to unravel the aspects: Why were female figurines placed in tombs? What are the artistic features specific to female figurines? What can we learn from the positions in which female figurines were placed? This paper will study examples of female figurine their artistic and social styles and draw comparisons to understand their development. As for the Feminine iconography in this period, we will show the depiction of woman on the antiquities since the age of Badari, with a discussing of the development of the feminine iconography, until the early dynastic era. Through these depictions, we will be able to-functional and social role through the depicted scenes on pottery vessels, mace heads, and tombs. The presence of feminine figurines and iconography in this early stage of the development of ancient Egyptian culture is indicative of the prominent role women essayed in daily life - as mothers, wives, and servants- an aspect the deceased wished to carry forward into the next world.

Keywords: feminine figurines, feminine iconography, predynastic iconography, prehistoric Egypt, prehistoric society, prehistoric sculpture, predynastic Egypt

Burial places in prehistoric Egypt were relatively straightforward; the deceased was typically laid to rest in pits along with its various possessions. During Badarian and Naqada I periods, graves were either oval or circular, with the body placed in a fetal position, often wrapped in goats’ skins or mats, and oriented towards the east, with the head facing south (For example, Badarian Tomb Nº. 5351 and Naqada Tomb. Nº1613).1,2 Funerary equipment was limited to pottery vessels, with some examples of ivory and bone combs, slate palettes and perhaps pottery figurines.1 In Naqada II, the grave design became more rectangular.2,3 However, the orientation of the body was reversed to face west instead.4 Funerary equipment, in this nascent stage of human civilization provides insight into the importance of women through their depictions of vessels and figurines made from ivory, clay, and stones. Although several studies have dealt with figurines and iconography from the prehistoric period, this paper will focus specifically on female figurines to better understand their development and the social role of women.

Badarian feminine figurines

Badarian civilization gave us the earliest known three-dimensional representations of the human shape discovered in Egypt. Thus far, eleven female figurines have been firmly dated to the Badarian culture. The other five come from Brunton’s excavation at Mostagedda-three from graves and two from settlement rubbish dumps, three of them were found by Brunton and Caton Thompson during their excavations at El-Badari, three in grave nos. 5107, 5227, and 569.1,5,6 They are made from ivory, baked and unbaked clay, as well as limestone. However, it is apparent that human sculpture was rare in the Badarian culture; among the three hundred graves discovered at El-Badari, only three figurines were discovered by Caton-Thompson.7

In Badarian culture, female figurines were represented with pronounced breasts, large buttocks and fleshy thighs and discernible private regions. The headless terracotta female figure (Figure 1)1 reflects the skill of the artist in the Predynastic era. In this specimen, not only has the sculptor expressed symmetrical feminine features, but he has also skillfully managed to express a certain kind of vitality, going by the delicate waist and breasts. It is worth mentioning that the big thighs were probably intended to reflect aspects of female fertility or the goddess of fertility herself. In contrast, the unbaked clay figurine of a woman (Figure 2) is not provided with arms or feet. The remnants of the head, in its present condition, protrudes in a beak-like shape.7

Figure 1 Figurine of baked-painted red pottery. British Museum, EA59679. BRUNTON & THOMPSON 1928: XXIV1.

Figure 2 Figurine of unbaked clay. Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London, UC 9080. PATCH 2011: 100, FIG.28.

Another ivory-statuette (Figure 3), from the same period, represents a nude woman with rugged features7 where it is noted that the head, nose, eyes are disproportionally large, and without hair and ears, as some of ivory figurines which appear without hair and ears.8 The sculptor appears to have used ivory owing to many reasons: the cohesion of its molecules, its suitability for carving, and the ability to polish it to a great degree. Above all, ivory is also less prone to damage than clay and pottery. However, it is clear from studying the artifact that its creator was a novice in the use of ivory, while Strudwick believe that the whole figure showing a remarkable degree of technical competence at a very early date in Egypt's history owing to it made with great care and polished to a fine finish.9 He inlaid the large eyes of the figurine with a different material, which was certainly a precursor for eye-inlays in sculptures of different materials in much later times. The deeply incised eyes and the drilled pupils may have been intended to be inlaid with other materials. Drilling was utilized to fashion nostrils in the prominent nose and to denote the nipples and lumbar dimples along the base of the back, a characteristic exclusive to female anatomy. The feminine attributes were emphasized through carving, whereas the arms appeared to lack delicate hand details. The diminutive, outwardly projecting feet were merely simple projections. It is worth noting that the general artistic characteristics of Badarian ivory-statuette appeared clearly in Cycladic marble-figurines, which came from the Cyclades, islands in the Aegean Sea dated to 2700 BC and 2400 BC (during the Early Bronze Age). For example, British Museum, 1863,0213.1.10 The feminine features on this ivory figurine could suggest that it was designed to symbolize fertility, possibly as a deity or concept,8 to aid the deceased in their journey to the afterlife or offer maternal protection during that journey. On the other hand, it might also represent the tomb owner's own rebirth and renewed vitality.9

The significance of these figurines can be partially identified; by analyzing objects and luxury materials such as steatite and turquoise discovered in the graves in which female figurines were found.6–11 Female figurines and associated finds help us assess the social and economic condition of the grave owner.

Naked Badarian figurines were probably the origin for nude statues that appeared in later periods. Scholars date the little statuette of Louvre Museum, E14205 to around the Early Dynastic Period. The position of the left arm is interesting: the upper arm is placed against the side of the chest, and the forearm is held horizontal beneath the breast, raising the shoulder a little. There are other archaic female figures represented similarly: those that have survived intact have the left hand cupped, as if originally, they were holding an object. In similar statuettes of the New Kingdom and Late Period (Compare with Brooklyn Museum Fund Nº.40.126.2),12 women are always shown holding an object (such as a cat or a bird).

In subsequent periods, especially the 18th dynasty, nude statues represent a child or decorative element, often intended to serve magical purposes. Most of these statuettes are made of ivory, like the Badarian artifacts already discussed here. Examples of such figurines made of wood have also come to light, such as the charming image of a naked young girl with an unusual hairstyle (i.e. hanging plaits) in British Museum EA32767, who peers at us from beneath the heavy load she carries.13 Despite being over 3 inches long, it is possible that this sublime female ivory figurine of Brooklyn Museum Fund 40.126.2 might have been worn as an amuletic pendant with sexual connotations. Another female statuette of Louvre Museum E 27429, which dates to the new kingdom, is shown wearing a short, fitted curled wig, with a wide unornamented band. In the top of the head, a square hole of undetermined depth can be seen covered haphazardly.14 Perhaps the purpose of this hole was to allow the figurine to be fastened to the rod of a tiny, circular, metallic mirror. Toiletry item handles frequently represented a nude young woman, the first Egyptians used mirrors in the Old Kingdom, if not earlier. The design of handles with the shape of papyrus plants symbolized the first moment when the sun-god emerged from the primordial swamp. The Egyptians picked up their mirrors each morning they were thus reminded of creation. In the New Kingdom, handles appeared in a wide variety of shapes, including animals, adolescent girls, and papyrus plants. Many of these objects are around 10-centimeters long with mirrors of around 10 centimeters in diameter. Although most mirror handles are made of wood or bronze, a fairly large number of ivory or bone handles exist.

Naqadian feminine figurines

During the Naqada Period, statuettes were made of ivory, clay, and limestone. Most represented standing and seated figurines of naked women with abundant physical features and braided hair. Female figurines from Naqada I (4000-3500 BC)15 seem to follow a more developed style. While many figurines appear to be sitting like Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, An1895.123b. The majority have stump arms and are missing their heads.6 Some of the seated figurines are decorated with incisions and markings in clay in zigzag style on the outer upper thigh, which could indicate tattoos.16 The seated figurine conserved in Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, An1895.123b shows a woman from el-Ballas, made of unbaked clay which indicates that she once had a complete set of features, including a smile.7

Some of the figurines from Late Naqada I depict a dancer. For instance, the unusual rim of a polished red ware pottery vessel of Egyptian Museum, Cairo, JE 99583 is decorated with eight dancing female figures with beak-like face shapes; they are shown wearing white skirts and holding hands.7

From the examples cited so far, we can conclude that while the figurines in early Naqada I depict nude women displaying sexual vitality, in Late Naqada I and early Naqada II, figurines are portrayed with tattoos and in dancing motifs.

All feminine figurines attributed to Naqada II (3500 -3200 BC)15 were found in graves particularly in the sites of Naqada, Abadiya and El-Ma’maryia.2,6,17 Some of these graves contained servant figures, destined to assist the deceased in the afterlife.7 For example, nude feminine figurines from Abadiya (Figure 4) show an emphasis on hairdressing, with noses significantly less beak-like in their appearance.

Figure 4 Pottery figurine. The Museum of Art, Rohde Island School of Design, 2000.82. PAYNE 1993: 313 (fig. 9.37).

Some of the statues attributed to Naqada II represented dancers with bird heads- probably to obscure the human element, or to express a connection with heaven or the surrounding environment. For example, one statuette in Brooklyn Museum, 07.447.505 shows a woman with a beak-like face, slender neck, raised shoulders, and pronounced breasts. Her waist is gracefully curved into uplifted arms with hands turned in and pointed; her legs are represented without feet7, and she wears a white skirt indicating an individual of high-status.

There is an excellent figurine from Late Naqada II in Metropolitan Museum of Art, MMA 07.228.71, which displays a beak-like nose and raised arms. The hair, narrow waist and wide hips shown in this specimen emphasize female sexuality. The black painted «tattoos» present on the chest, back, and upper thighs clearly relate to how this statue was used in the Predynastic period. On this figurine, partial scenes of animals are depicted on the front and back, while the buttocks show what appear to be petals or leaves. Other examples show zigzag lines, perhaps representing water. These scenes probably represented elements of the Nile Valley landscape. The seated position of the figurine enables it to be placed upright on a surface. Considering the emblematic images painted on the body, it is suggested that the statuette had an important role in some ritual in Predynastic society, but what it was is still unknown.7 This figurine, bearing geometric patterns on its arms and legs, is considered the best example -among the earliest pieces of such circumstantial evidence -for tattooing in Predynastic Egypt. While these geometric patterns have been interpreted as tattoos, it is impossible to distinguish markings used as tattoos from those used as decoration.19,20

Some of the feminine figurines represented characteristics of motherhood, as in the pottery figure of a woman holding a child of British Museum, EA30725 shows applied hair-locks (most lost) and two neck-rings; skirt represented by incised chevrons on the cursorily modelled legs; child’s right arm broken away.

In Naqada III (3200-3000 BC),15 there is a good example of an ivory statuette (British Museum, EA32143) of a woman holding a child. This sculpture shows the infant clutching the mother, whose arm bends to caress the baby’s head. She wears a long dress with a fringe that leaves her left breast exposed, reinforcing the nurturing aspect found in such figural representations. Unfortunately, the mother’s face is missing. This statue may reflect an appeal to the local temple deity to facilitate motherhood, and gratitude to a deity who granted such a request, or protection for the infant.7 Also, Female statues also express the political role of women as a king’s wife or a royal princess (Fay, Royal Women as Represented in Sculpture During the Old Kingdom Part II: Uninscribed Sculptures, 1998) as shown by the Egyptian Museum, Cairo JE 71586, which was found in Hierakonpolis. The statue represents an early queen and because the statue is not inscribed, her identity and name remain unknown. Her wig is similar in shape to wigs made from organic paste found on many Predynastic figurines, such as the objects nos. Kofler Collection Lucerne K415, Staatliche Sammlung Agyptisches Kunst Munich, 4234, and Ashmolean Museum Oxford, E. 322. There are many female statuettes that may express a high social status or a high political status for women (i.e. as queen) because of the quality of their craftsmanship and their distinction from others. For example, the statuettes nos. Louvre Museum, E 11888, Ashmolean Museum, E. 326-328, and University Museum Philadelphia, E 4895.

The purpose of placing feminine figurines with the deceased in their burials conveys the following messages: it could symbolize the mother who will give birth to the dead individual in the next world, the wife who will accompany him into the hereafter, the dancer who will please his heart, or the servant who will prepare his food. Moreover, the political rule of females appeared obviously in the statuettes of Naqada III.

Badarian feminine iconography

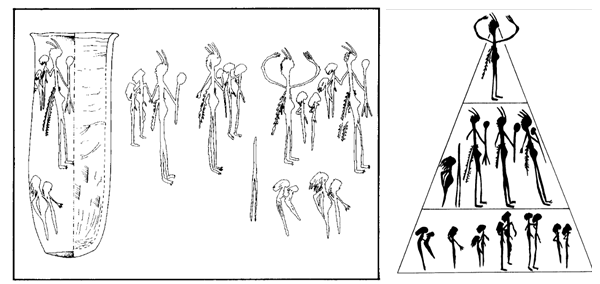

This section analyzes the depiction of dance motifs on pottery vessels by methods such as application or incisions during the Badarian and early Naqada I phases. The earliest known instances of these themes have been reported from the Badarian culture (Figures 5–7). It should be noted that some of the first depictions were applied or incised and not painted.21 The arms of the human-like images in the representations are lifted upwards with hands curving inward; a gesture typical of ritual in Predynastic Egypt, found on many clays’ female figurines (see above). Some scholars have suggested that raised arms imitate bovine horns of the goddess Hathor, a postulation that has its merits.22–25

Naqadian feminine iconography

In Naqada I, the artist showed the female body using simple lines and brief details. He displayed the head as a point without details and distinguished it with long hair. The upper part of a woman’s body is depicted like a reversed triangle and the lower part is drawn with two vertical lines. The human activities in these scenes focus on dance- either of a religious nature or from daily life. Men and women are shown dancing together or separately (Figures 8-9). For example, the vessel in (Figure 8) depicts a man and a woman dancing together, but the woman appears without arms; whereas the vessel in (Figure 9) shows two men dancing beside six women who are portrayed on a smaller scale. The men can be identified by way of their raised arms, while the women positioned closest to the males raise only one arm.27 In both scenes, men are distinguished by their phalluses and women by round rings.28

Figure 8 Vessel showing dancers. Petrie Museum, UC 15339. PETRIE 1909: 55, fig. 6; PETRIE 1921: pl. XXV-100; SCHARFF 1928: Fig.4.

Figure 9 Vessel showing a group of dancers. Musees Royales d’Art et d’Histoire, E 3002. BAUMGARTEL 1947: Fig. 14.

Despite acknowledging the clear diagnosis mentioned above, it is essential to recognize that earlier researchers such as Petrie, Scharf, Willliams, Hendrickx and Davis observed that there were no women on these vessels. Petrie briefly mentioned that the scenes on the vessel (Figure 8) depicted a fight between two men. He stated that the long-haired man, who was likely a prehistoric individual wearing a sheath and long hair, was successfully attacking the short-haired man, who wore a hanging appendage, possibly a dagger sheath. Neither figure seemed to have any additional clothing.25,31 Scharff identified the eight human figures on this vessel (Figure 9) as men. He noted that two of the figures were taller than the others by more than a head, and these two tall figures extended their arms upwards.25,28 Williams recommended that the tall figures (Figure 9) should have branches or feathers in a fan-like arrangement on their heads. Behind the waists of the figures, there are objects composed of a shaft and a round knob. Although these objects have been identified as phalloi, they extend from the backs of the figures, making it more likely that a mace is depicted instead of a phallus. He perceived the tall figures as rulers or deities, and the small figures as prisoners of war connected to the tall figures by cords around their necks. Thus, the scenes portray the victory or the triumphant sacrifice and the sacrifice before the palace facade or serekh.32 This interpretation has been endorsed by Hendrickx, who analyzed the Brussels vessel in detail33,34 and published the first technical drawing of item.35 The Petrie original interpretation of the scene on the London vessel was later extended to the Brussels vessel by Davies which stated that Petrie intended to differentiate two groups of people, one tall and possibly hairy-legged with a short-haired figure and a dagger in a sheath, while the other was shorter and long-haired, wearing a penis sheath and carrying a spear.36

Petrie and other scholars consistently mistake women for men, and thus cannot explain the differences in the depiction of the figures according to Baumgartel that stated (Figure 9) Eight figures, portrayed in full front view with both legs visible, are represented. Two of these figures, larger than the rest, are men. They are depicted in an attitude of dancing, with their arms raised, demonstrating the same pose as the man on the white painted vase with the dancing couple currently housed in University College, London (Figure 8). The two men on the Brussels vase (Figure 9) sport short, curly hair shown as dots around their heads; twigs are inserted into this hair. Along their legs are rows of dots that may indicate the roughness or hairiness of their skin, contrasting with that of the women; outside the body, this is a crude method the artist employs to distinguish between the sexes (Scharff consistently mistakes women for men, and thus cannot explain the differences in the depiction of the figures). The women dance in a line between the men, paired off. Two of these women encircle one of the large male figures. The woman closest to it raises one arm, placing it on the man's shoulder, while the one farther away lays hers on the shoulder of the woman in front of her. The other man seems to be dancing by himself, unaccompanied by the remaining pair of women. One of these women is portrayed without arms, while the other, farther from the man, appears to gesture away from him with her arms. The last woman in the scene is depicted at a smaller scale compared to the others, allowing for the suspension of a symbolic object above her.

Additionally, there is another large object hanging beside it, extending all the way down to the base of the vase. The significance of these objects remains unclear, and it is not immediately apparent how they relate to the ritual being performed.25,27 Baumgartel’s point of view that the scene represents a dance shared by men and women has been supported by many researchers as Vandier,37 Murray,22 Asselberghs,38 Vermeersch & Duvosquel,39 and Garfinkel.40

However, the gender division suggested by Baumgartel has not always been accepted and sometimes the entire group has been understood as composed of female figures.22,39 After presenting all these opinions, I can determine what the shapes are and adopt Baumgartel’s point of view because the bodies of women on pottery match the female statues in terms of the simple body details of the woman and the position of raising the arms up.

A notable vessel (Figure 10) was discovered in Grave U-239, which dates to the Naqada I phase. It is covered with a black slip bearing a white paint scene. The depicted scene has been interpreted as depicting a conflict between two groups, although this has not been conclusively established through a systematic analysis of the depiction itself. The main argument is based on a comparison with the later wall painting from Hierakonpolis.41 However, the four tall figures in the upper row emphasized bellies. This element may be a female gender characteristic, possibly indicating pregnancy. In contrast, the small figures do not have emphasized bellies, but some of them exhibit a penis. The scene appears to depict a hierarchical order of three levels: 1) The leading person, who is presented with raised arms, folded hands, and clear finger indications. This body posture is commonly observed in Predynastic Egypt and appears on several clay figurines, decorated jars (Figures 5 & 6), rock carvings, and fragments of a painted linen shroud. 2) The other five tall individuals, especially the more realistic ones from the upper row, have an impressive appearance, complete with elaborate head decoration, an elongated object, and clothing. The last girl in this row has hair and some of her features like those of the girl who is dancing with the man on the vessel of Petrie Museum (Figure 8). 3) Eleven small figures: these are typically positioned in pairs around a tall figure. In many cases, they are holding hands with each other and with a tall figure. The notable discrepancies in the height of the various characters in the Abydos scene effectively explained by Garfinkel that proposed two potential explanations: 1. Actual differences in height that signify age, where older individuals are depicted taller and younger ones shorter. 2. The disparities in height represent a hierarchy of importance, where larger figures hold greater significance and are thus portrayed larger, while smaller figures are of lesser importance and are shown in smaller size. A combination of both age and importance seems to be the most suitable explanation for the differences in the depiction of the characters in our case. It is also worth noting that when gender is considered, the taller, more elaborately dressed figures are female, while the shorter, naked figures are male. This suggests a scene featuring adult women and adolescent boys.25

Figure 10 Vessel from Abydos and the hierarchal order of its scene. DREYER et al. 1998, figs. 12:1 & 13; GARFINKEL 2001, 242.

In Naqada II, the dancing woman is represented in red color amidst the Nilotic landscape (including boats and aquatic fauna).21 Unlike the dancing figures of men, the ones of women mainly represent them raising their arms over their heads in curved arches. Feminine figures were depicted with little detail: their faces were shown in front view; the upper portions, drawn as reversed triangles, ended in thin waists; the lower part of their bodies have been displayed in triangular shape, below which are the women’s legs Museum of Arts, MMA 20.2.10.7 The artistic concept of depicting women’s feet in Naqada culture continued to be portrayed in feminine statues and iconography even in subsequent periods.43,44 This feature apart, in later eras, a woman’s head could be interpreted as a bird head;45 her raised and curved arms as imitating bovine horns22–24 and her hands as resembling a cow’s triangular ears -and so on. This manner of depicting women indicates the artist’s desire to incorporate elements found in other representations.45 Therefore, raised arms, the horns of a bull (or cow), and the necks and heads of birds are combined to create human representations. This principle is echoed in the integration of elements found on decorated pottery.45

Large figures on jars can be definitively identified as females and the smaller figures as males. Clearly subordinate, the male figures face the females who present curved objects. The dominant position of women on decorated vessels can refer to self-evident symbols of life and rebirth. For example, a jar (Figure 11) shows a large woman dancing with cow-goddess’ arms. On one side, her two smaller male companions create a rhythm with clappers or castanets.23 The female figure is obviously important, perhaps a goddess or priestess. The men who actively serve as mediators summon the goddess from her sacred boat, probably desire to imbibe her blessings and power. These scenes may also depict a funeral procession and associated rituals as similar motifs are known from desert rock art. The message may be much broader with motifs forming part of a graphic vocabulary expressing ideas about fertility and rebirth, whether of humans or the cosmos.

Another jar (Figure 12) bears painted scenes of many-oared ships and standing human figures, including dancing women. A curved motif, identified as double horns, and crossed lines, depict the emblem of goddess Neith. Above the boats stand human figures. A large female figure with arms imitates bovine horns, with a smaller male figure on the left holding her arm. To the right, another male figure facing the emblem of Neith holds a curved staff. I opine that this scene shows a woman performing the role of a priestess of goddess Neith. The woman represented thus may also be a goddess herself, due to her depiction in equal size with the symbol of Neith, as well as the man beside the woman with the emblem.

Also, there is a statistical relation between female figures and animals depicted on vessels. For example, a jar (Figure 13); shows a connection between the depicted addaxes and female representations above boats. The addax must have been a funerary symbol of some sort.49

Dancing scenes lost their importance in Naqada III. This development is best demonstrated on the famous Hierakonpolis wall (Figure 14), wherein dancing is by no means the center of the representation. However, there is a faint echo of its significant role in symbolic expressions of Predynastic Egypt.21

Figure 14 Dancing women on the wall of tomb no. 100 in Hierakonpolis. QUIBELL & GREEN 1902, pl. LXXVI.

Another example from Naqada III appears on the mace-head of a ruler called Scorpion (Figure 15). The upper scene represents two seated women, only one of whom is visible, and a person holding a stick standing behind them. The women may be princesses captured during the king’s wars in the Delta. The lower panel shows a dancing scene, with the ladies discernible by their long hair and tight-fitting clothes that reach down to their knees. This representation possibly shows a celebration to commemorate king Scorpion uniting Egypt or for his success in digging a canal.51,52 The depiction of women on the mace-head reflects the skill of artists in this period.

The presence of feminine figurines and iconography in this early stage of the development of ancient Egyptian culture is indicative of the prominent role women essayed in daily life - as mothers, wives, and servants - an aspect the deceased wished to carry forward into the next world. The scenes depicted on pottery show women as dancers, priests, and goddesses. The feminine figurines show woman as mother, wife, and servant.

The advent of nude feminine figurines can be noted in the Badarian culture, while dancing figurines appeared in Late Naqada I. The former category of feminine images did not appear in subsequent periods until the 18th dynasty. Made from ivory, clay (on a large scale), and limestone (on a lesser scale) nude figurine were used in the 18th dynasty as decorative elements and as amulets imbued with magical purposes.

Badarian ivory-figurines (3700 B.C) look like Cycladic marble-figurines (2700 B.C) in general characteristics such as nudity, tough face features (big head and nose), and bandy legs. Tattoos on feminine figurines appeared in Naqada I; they have patterns that imitate the local environment.

Females were for the first time depicted as dancers on Badarian pottery. Females were shown on Naqada pottery with males, on a small scale, dancing with each other. In Naqada II, most of the scenes were of women who appeared dancing and standing inside boats. These dances may have had religious purposes or could reflect daily life. In Naqada III, the depiction of women was more advanced in physical details and movements-such as is etched on the Scorpion mace-head. It was, however, considered a secondary scene according to tomb no. 100 in Hierakonpolis.

The religious significance of feminine figurines is revealed in connection to females and the world of deities. The full thighs of the Badarian female represent the goddess of fertility; the raised arms express association with goddess Hathor (as the position of the hands simulates the horns of the cow); and the beak - like shape shows the connection with heaven. The depiction of women in pottery with emblems of deities (For example, goddess Neith) as the main character, not a secondary one, often refers to their important religious role - for they were likely venerated as a goddess or priestess (Appendix).

Figurines and iconography also serve to indicate that women played an important social role. Tattoos drawn on feminine figurines signal a religious not funerary purpose. Also, representation of women in smaller size in Naqada I pottery reflects the distinguished social position of males; while their depiction in Naqada II art in a much larger size than menfolk reveal the greater social position, they attained during this period.

None.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

©2024 Abdelhafez. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.