eISSN: 2377-4304

Research Article Volume 13 Issue 4

1Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, University and Polytechnic La Fe Hospital,Valencia, Spain

2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Manises Hospital, Valencia, Spain

3Data Science, Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria La Fe,Valencia, Spain

Correspondence: Alicia Martínez-Varea, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, University and Polytechnic La Fe Hospital,Valencia, Spain

Received: June 27, 2022 | Published: July 11, 2022

Citation: DOI: 10.15406/ogij.2022.13.00650

Objectives: Analysis of success variables of cervical ripening with the Foley catheter in patients with prior cesarean section (PCD), post-term pregnancy (PP), and a Bishop score £6. Evaluation of technique’s safety.

Study design: Prospective cohort trial in which 120 patients were enrolled, from April 2014 to May 2018. PCD was codified in four groups: 1) failed Induction (FI); 2) non-progressive labor (NPL) or cephalopelvic disproportion (CPD); 3) abruptio placentae (AP), risk of fetal distress (RFD) or placenta previa; or 4) other causes.

Inclusion criteria: singleton pregnancy; >40+6 weeks’ gestation; cephalic presentation; Bishop Score £6; PCD >18 months; signed consent of vaginal delivery (VD).

Exclusion criteria: myomectomy with entry into the endometrial cavity; >1 PCDs or uterine rupture; other presentations; macrosomia; multiple pregnancy; placenta or vasa previa; premature rupture of membranes (PROM); inferior genital tract infection.

Used material and protocol: Foley catheter insertion at 9 am, followed by 2 hours of fetal cardiotocograph register (CR). This was repeated 6 hours later. Catheter removal 12 hours after the insertion. Intravenous oxytocin was started at 8 am the following day.

Statistical analysis: multivariable logistic regression to assess the similarity of populations. Assessment of the relation between VD and APL with the PCD indication and the CL through logistic regressions. The analysis were performed using R (3.5.1), clickR packages (0.3.64), and Boot Validation (0.1.6).

Results: A total of 86/109 (78.9%) achieved APL. Whereas 52/86 (60.47%) finished by VD, 34/86 (39.53%) had a cesarean delivery (CD). No significant differences were found between populations. PCD indications for AP, RFD or placenta previa (OR = 7.85 IC95% [1.87, 39], p=0.007) have a higher likelihood of VD. The PCD indication for NPL or CPD; and AP, RFD and placenta previa, have a higher likelihood of achieving APL (OR 14,55 [IC 95% 2.01, 308.5], p=0.023; OR 15,81 [IC 95% 2.03, 359.78], p=0.024; respectively). As CL was higher, the likelihood of APL was lower (OR=0.92 IC95% [0.84, 0.99], p=0.034). No uterine rupture registered.

Conclusions: Cervical ripening with the Foley catheter was satisfactory in 78.9% (86/109). PCD indications that are different from FI associate a higher likelihood of VD. CL has a decreasing effect on the likelihood of APL. The Foley catheter is a safe method for cervical ripening.

Keywords: Foley, cervical, ripening, cesarean, post-term, pregnancy

Cesarean delivery is an option for pregnancy termination in patients with a prior cesarean delivery (PCD), post-term pregnancy (PP), and an unfavorable Bishop score (£6). This is because of the risk of uterine rupture, which varies between 0.5 and 2.9%, due to the presence of a prior uterine scar.1–5 Labor induction in patients with PCD, PP, and a Bishop score £6 can be preceded by cervical ripening prior to oxytocin infusion to reduce the rate of elective CD and CD because of failed induction (FI). This consists of an improvement of the cervical conditions through a physical or pharmacological method prior to labor induction with an oxytocin endovenous infusion.6–9

Although there are several methods for cervical ripening, there is no consensus about which one is the safest and most effective one in patients with PCD and PP. Additionally, there is still a lack of data about the method associated with a lower uterine rupture rate and a higher VD rate.6,9

One of the most used methods for cervical ripening in patients with PP is the administration of vaginal prostaglandin (PG). Among those, misoprostol (PGE1) and dinoprostone (PGE2) are the most used ones. However, in patients with PCD, there is a lack of randomized trials with a considerable sample size. Most existing data were obtained from observational trials, most of them using PGE1. Regarding PGE2, the existing studies are limited by sample size, coadministration of other drugs, or lack of stratification of the patients based on the history of previous VD. Moreover, the results of these studies are contradictory. On the one hand, in 2001, a study was published that stated a relative risk (RR) increase (RR 15.6 [CI 95% 8.1–30.0]) of uterine rupture when the use of PG was compared with an elective CD, spontaneous labor, or labor induction without PG.2 On the other hand, in 2004, no statistically significant results were obtained about the increase of the risk of uterine rupture when the use of PG was compared with other methods of cervical ripening in patients with PP and PCD.5 These contradictory results could be due to the lack of a protocol regarding the use of PG (even in the dose and the type of PG), as well as the presence or absence of subsequent oxytocin infusion. For these reasons, it remains unclear if the increased risk of uterine rupture is due the use of PG or the combination of it with oxytocin.

There are just a few trials regarding the use of PG isolated for cervical ripening. In 1998, Wing DA et al.10 performed a randomized trial which used PGE1 for cervical ripening. The trial had to be finished earlier than expected due to safety reasons and revealed that PGE1 is associated with a higher risk of uterine rupture when it was compared with other PG. Therefore, the authors concluded that PGE1 has to be avoided in patients with PCD.10 Nowadays, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) and the Canadian Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (CSOG) do not recommend the use of PGE1 for cervical ripening in patients with PCD.7,8 Nonetheless, the CSOG allows the use of PGE2 in some cases.8 On the contrary, the NICE guidelines state that PG could be used in patients with PCD as long as a careful and individualized indication is carried out.11

Due to the controversial results regarding the safety of PG in patients with PCD and PP,2,5,10 an alternative method of cervical ripening with at least the same effectiveness of PG is needed. In this sense, mechanical cervical ripening with the Foley catheter is based on the introduction of this catheter trough the external cervical ostia (ECO) until it exceeds the internal cervical ostia (ICO), without inducing a premature rupture of membranes (PROM). Once the catheter is introduced, its balloon is filled with >30ml of sterile water.12 Thus, detachment of the amniotic membranes is achieved, triggering a physiological production of PG that induces cervical ripening.

The safety of this method has been widely studied. Various studies have concluded that the Foley catheter is a method of cervical ripening in patients with PCD, PP, and a Bishop score £6, not increasing the risk of uterine rupture and being associated with a low rate of maternal-fetal complications (1–12%). Therefore, some authors describe this procedure as a cost-effective technique for cervical ripening in this subset of patients due to the safety, low cost and the associated VD rates, particularly when it is combined with subsequent oxytocin infusion.1,13–16 The only contraindication of this technique is the existence of a previous PROM because a foreign body inside in a, theoretically, sterile cavity could increase the risk of chorioamnionitis.17

Regarding the effectiveness of cervical ripening with the Foley catheter when compared with PG use, both methods have similar VD and CD rates (6–38%).13,18–21 However, the time since the beginning of the application until APL is lower those patients in whose the Foley catheter was used.19,20

In conclusion, the Foley catheter could be a safe option for cervical ripening in patients with PCD, PP, and an unfavorable Bishop score. Thus, the present study aims to determine which variables could help to predict a better response to mechanical cervical ripening, with the aim to select those patients which can most benefit from this approach.

Objectives

The main objective of the present study was the analysis of the predictive variables of success of mechanical cervical ripening with the Foley catheter in patients with PCD, PP, and a Bishop score £6 and who desired a VD after a PCD. It was considered as success to achieve APL after the placement of the Foley catheter and the subsequent intravenous infusion of oxytocin. The intention is to identify those patients with PCD, PP, and an unfavorable Bishop’s index who can benefit most from mechanical cervical ripening and subsequent oxytocin infusion to achieve APL and, finally, VD.

The secondary objective was to study the safety of mechanical cervical ripening in pregnant women with PCD, PP, and an unfavorable Bishop index, used before labor induction with oxytocin. Specifically, the uterine rupture rate, maternal complications (such as uterine atony, chorioamnionitis), as well as neonatal morbidity will be analyzed.

Study design: The present study is a prospective cohort trial performed at the University and Polytechnic Hospital La Fe (Valencia, Spain). From April 2014 to May 2018, a total of 120 patients with PCD, PP, and an unfavorable Bishop score, as well as desiring VD after PCD, were enrolled to undergo mechanical cervical ripening with the Foley catheter prior to intravenous infusion of oxytocin for labor induction. All included patients freely signed an Informed Consent where the technique was explained, as well as the risks and benefits of the procedure. Of the 120 recruited patients, 11 revoked the informed consent and were excluded from the study. Data and statistical analyses were performed including the 109 remaining patients. The patients enrolled in the study did not receive any compensation for their participation.

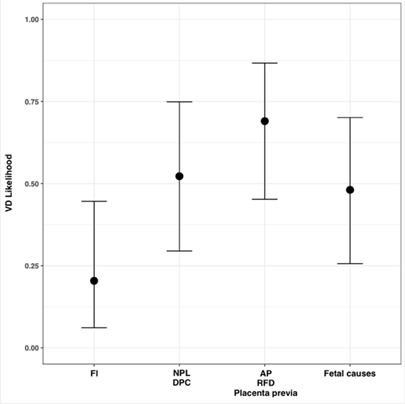

For prior assessment, the Bishop score was used to standardize the subjectivity of the gynecologist’s assessment (Figure 1). The PCD indication was codified in the following four groups: Failed Induction (FI); non-progressive Labor (NPL) or cephalopelvic disproportion (CPD); abruptio placentae (AP), risk of fetal distress (RFD) or placenta previa; or other fetal causes.

Figure 1 Vaginal delivery odds ratio according previous cesarean delivery indication.

VD, vaginal delivery; FI, failed induction; NPL, non-progressive labor; CPD, cephalopelvic disproportion; AP, abruptio placentae; RFD, risk of fetal distress.

Inclusion criteria. All pregnant patients with PCD and desiring VD who met the following criteria were included:

Exclusion criteria. All patients who met one or more of the following criteria were excluded from the study:

Used material and protocol: Patients who were included in the study underwent a vaginal ultrasound to determine the cervical length. Then, vaginal disinfection was performed with aqueous chlorhexidine, and a FR 22 silicone Foley catheter (Coloplast®) was placed into the cervix. Catheter insertion was performed with extreme caution, under ultrasound guidance, until exceeding the ICO with the catheter’s balloon, without provoking amniorrhexis. After insertion, the balloon was filled with 40–50ml of sterile water. Once insertion was accomplished, the catheter was fixed to the inner thigh with an adhesive plaster without any tension. If the patient had a group B Streptococcus-positive culture, prophylactic antibiotics were administered at the beginning of the technique (ampicillin 2g intravenously and subsequently 1g each 4 hours).

After catheter insertion, a long CR was performed for 2 hours. In case it was satisfactory, the patient could move freely, and 6 hours later, another CR was placed for 30 minutes.

Catheter insertion was scheduled at 9.00 am for all pregnant women. After 12 hours, all patients were assessed. The catheter was withdrawn, and a vaginal examination was performed. If the patient met the APL criteria (≥3cm of cervix dilation and complete cervical effacement), she was moved to the dilation room. If the patient did not meet those criteria, she was left in spontaneous evolution until 8.00 am of the following day, when the oxytocin infusion was started.

Statistical analysis: The two population groups were compared via a multivariable logistic regression. The assessment of the relation between VD and APL with PCD indication, CL, and other variables of interest was performed through two logistic regressions. Furthermore, age, weight, and previous VD were added to the model, considered as possible confusion factors. The non-linearity of the CL effect was modeled but was not included in the final models. All analyses were performed using the statistical software R (3.5.1); clickR packages (0.3.64) were used for data management, and BootValidation (0.1.6) was used for model validation.

A total of 86 out of 109 patients (78.9%) achieved APL with the combination of the Foley catheter and subsequent oxytocin infusion. The 23 patients who did not meet the APL criteria underwent a CD with FI as indication in all cases.

Of those patients who achieved APL (86), 52 out of 86 (60.47%) finished their pregnancy by VD and 34 out of 86 (39.53%) by CD. Among all included patients, 52 out of 109 (47.71%) finished their pregnancy by VD and 57 (52.29%) by CD.

Among the patients who achieved APL and pregnancy termination was via CD, the CD indication was NPL or CPD in 28 (49.12%) cases, FI in 15 (26.32%) cases, and RFD in 13 (22.81%) cases. In one patient (1.75%), CD was indicated for another reason – specifically, fetal presentation of the hand.

A comparative study between patients who finished their pregnancy with VD and those who finished with CD was performed through a multivariable logistic regression. No significant differences were found between both populations (VD vs CD) regarding patient age (CD 34.75±3.55; VD 33.5±4.55), Bishop score after catheter withdrawal (CD 5.29±1.96; VD 5.85±2.27), difference between Bishop score before the placement of the Foley catheter and after its removal (CD 2.76±2.12; VD 3.29±2.39), newborn weight (CD 3,423.6±354.9g; VD 3,373.2±458.1g), history of previous VD (CD No 51 vs Yes 6; VD No 43 vs Yes 9), or PCD indication, except for PCD due to FI, which was statistically significant (OR 3.39 [IC 95% 1.105 1.51]) (Figure 2).

A logistic regression model was fitted to relate the VD with the variables. The PCD indications for NPL or CPD; AP, RFD or placenta previa; or other fetal causes were associated with a higher likelihood of VD than the PCD indication for FI. Nonetheless, the only indications with statistical significance in this relationship were AP, RFD, or placenta previa (OR=7.85 IC95% [1.87, 39], p=0.007) (Figure 3). Furthermore, even without a statistically significant difference, the analysis revealed that the VD likelihood decreases as the age (Figure 4) and CL (Figure 5) increase (OR 0.911, IC95% [0.79, 1.031], p=0.159, OR 0.957, IC95% [0.9, 1.014], p=0.145, respectively).

Figure 3 Relation between cervical length measured in millimeters and vaginal delivery likelihood.

VD, vaginal delivery; CL, cervical length.

Figure 4 Relation between active phase of labor likelihood and prior cervical length measured in millimeters.

APL, active phase of labor; CL, cervical length.

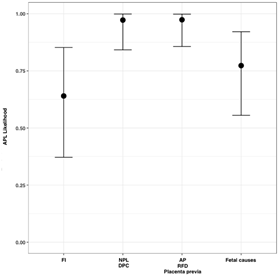

Figure 5 Active phase of labor OR regardin previous cesarean delivery indication.

APL, active phase of labor; FI, failed induction; NPL, non-progressive labor; CPD, cephalopelvic disproportion; AP, abruptio placentae; RFD, risk of fetal distress.

The PCD indication for NPL or CPD; and AP, RFD and placenta previa had a higher likelihood of achieving APL (OR 14,55 [IC 95% 2.01, 308.5], p=0.023; OR 15,81 [IC 95% 2.03, 359.78], p=0.024; respectively). As the CL by ultrasound was higher, the likelihood of achieving APL was lower (OR=0.92 IC95% [0.84, 0.99], p = 0.034) (Fig. 8). All these associations were statistically significant.

Regarding maternal-fetal complications, it should be noted that there were no uterine rupture, fetal cardiac rhythm alterations during mechanical cervical ripening, or infectious maternal-fetal complications. One patient presented uterine atony (0.92%), which was controlled with pharmacological therapy. Three (2.75%) newborns had a pathological cord blood pH from the umbilical artery (arterial pH <7.10), two of them with an Apgar score <7 at the first minute. A total of 10 (9.17%) newborns had an Apgar score <7 at the first minute, with a normal cord blood arterial pH. All newborns had normal Apgar scores at 5 minutes (Tables 1–4).

Bishop’s index |

||||

Score |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

Parameters |

||||

Dilation (cm) |

0 |

1 a 2 |

3 a 4 |

≥5 |

Effacement (cm) |

> 4 |

≤4-≥2 |

<2- ≥1 |

<1 |

Presentation |

Free |

Over narrow |

First level |

Second level |

Consistence |

Hard |

Medium |

Soft |

|

Cervical position |

Posterior |

Medial |

Anterior |

|

Table 1 Bishop score

Variable |

CD (n = 57) |

VD (n = 52) |

Multivariable P-value |

O.R (IC95%) |

Age |

34.75 (3.55) |

33.5 (4.55) |

0.199 |

|

Post Bishop’s index |

5.29 (1.96) |

5.85 (2.27) |

0.264 |

|

Bishop’s Index variance |

2.76 (2.12) |

3.29 (2.39) |

0.894 |

|

Newborn weight |

3423.63 (354.93) |

3373.17 (458.12) |

0.711 |

|

History of VD |

||||

No |

51 (89.47%) |

43 (82.69%) |

||

Yes |

6 (10.53%) |

9 (17.31%) |

0.34 |

1.809 (0.545-6.449) |

PCD indication |

||||

FI |

18 (31.58%) |

7 (13.46%) |

0.039 |

3.39 (1.105-11.51) |

NPL or CPD |

11 (19.3%) |

13 (25%) |

||

AP, RFD or placenta previa |

10 (17.54%) |

9 (17.31%) |

||

Other |

18 (31.58%) |

23 (44.23%) |

|

|

Table 2 Baseline characteristics of enrolled patients

CD, cesarean delivery; VD, vaginal delivery; OR, odds ratio; PCD, previous cesarean delivery; FI, failed induction; NPL, non-progressive labor; CPD, cephalopelvic disproportion; AP, abruptio placentae; RFD, risk of fetal distress.

|

Estimate |

Std. Error |

OR |

Lower 95% |

Upper 95% |

P-value |

(Intercept) |

4.576 |

3.561 |

97.132 |

0.142 |

183291.147 |

0.199 |

History of VD |

0.729 |

0.768 |

2.073 |

0.477 |

10.32 |

0.343 |

Neonatal weight |

0 |

0.001 |

1 |

0.998 |

1.001 |

0.54 |

Maternal age |

-0.093 |

0.066 |

0.911 |

0.793 |

1.031 |

0.159 |

PCD for NPL or CPD |

1.41 |

0.751 |

4.095 |

0.989 |

19.695 |

0.061 |

PCD for AP, RFD or placenta previa |

2.062 |

0.768 |

7.858 |

1.873 |

39.575 |

0.007 |

PCD for other causes |

1.247 |

0.732 |

3.481 |

0.872 |

16.154 |

0.089 |

Prior CL |

-0.044 |

0.03 |

0.957 |

0.9 |

1.014 |

0.145 |

Table 3 Logistic regression for vaginal delivery

VD, vaginal delivery; PCD, previous cesarean delivery; FI, failed induction; NPL, non-progressive labor; CPD, cephalopelvic disproportion; AP, abruptio placentae; RFD, risk of fetal distress; CL, cervical length; OR, odds ratio.

|

Estimate |

Std. Error |

OR |

Lower 95% |

Upper 95% |

P-value |

(Intercept) |

1.918 |

5.049 |

6.805 |

0.001 |

265028.17 |

0.704 |

History of VD |

0.314 |

0.977 |

1.37 |

0.229 |

12.248 |

0.748 |

Neonatal weight |

0.001 |

0.001 |

1.001 |

0.999 |

1.003 |

0.404 |

Maternal age |

-0.039 |

0.088 |

0.961 |

0.798 |

1.134 |

0.653 |

PCD for NPL or CPD |

2.678 |

1.178 |

14.553 |

2.006 |

308.496 |

0.023 |

PCD for AP, RFD or placenta previa |

2.761 |

1.224 |

15.812 |

2.027 |

359.777 |

0.024 |

PCD for other causes |

0.656 |

0.725 |

1.927 |

0.468 |

8.35 |

0.365 |

Prior CL |

-0.086 |

0.041 |

0.917 |

0.842 |

0.99 |

0.034 |

Table 4 Logistic regression for active phase of labor

VD, vaginal delivery; PCD, previous cesarean delivery; FI, failed induction; NPL, non-progressive labor; CPD, cephalopelvic disproportion; AP, abruptio placentae; RFD, risk of fetal distress; CL, cervical length; OR, odds ratio.

The present prospective cohort study, in accordance with previous trials,14,23,24 reveals that the Foley catheter is an effective method for cervical ripening in patients with PCD, PP, and an unfavorable Bishop score. Particularly, the use of the Foley catheter for cervical ripening in patients with PCD, PP, and a Bishop score £6, with subsequent oxytocin infusion, induced APL in approximately 80% of the patients, and 60% of them achieved VD. Furthermore, approximately half of the patients who underwent cervical ripening with the Foley catheter, with subsequent oxytocin infusion, had a VD. Jozwiak et al.13 concluded, in a retrospective cohort trial in 2014,24 that approximately 60.1% of the patients achieved a normal VD, and 71.1% when those patients who underwent vacuum extraction were included. The authors concluded that the Foley catheter is an effective method for cervical ripening in patients with a PCD. Emmanuel Bujold performed a trial1 where the VD rates where similar to those in the present study (55.7%). Our results are also consistent with those obtained in 2015 in a study performed for Lamourdedieu et al.,14 where 61.5% of the patients reached APL and 43.5% ended their pregnancy with a VD. The CD rate in our study was 52.29%, which is also in accordance, although discreetly higher, with most of the published trials (39–49%).1,3,4,14 Jozwiak’s trial24 revealed a lower CD rate, which may be due to the Nederland’s obstetric tradition, a country with a low CD rate (12% in 201825 compared to 25.72% in Spain in 2018, according to the Statistics National Institute). This difference in the CD rate might also be due to the fact that in the Dutch trial, the Foley catheter was left inserted for 4 days, while in our study and in other similar ones,1,3,14 it was left only for less than 24 hours (more precisely, 12 hours).

One of the strengths of the present study is its homogeneous sample group. In this sense, there were no statistically significant differences regarding the characteristics of those patients with PP, PCD, and a Bishop score £6 who underwent mechanical cervical ripening with subsequent oxytocin infusion and finished the pregnancy with a CD vs those who finished the pregnancy with a VD. Only statistically significant differences were observed regarding the prevalence of PCD for FI in the group who finished their pregnancy with an iterative CD. Moreover, this is a prospective cohort study with a non-negligible sample of patients with PCD, PP, and a Bishop score £6 and who desired to achieve a VD to avoid an elective CD. All pregnant women were treated following a specific hospital protocol to homogenize the treatment and the data collection. All data were obtained from the patients’ medical records.

Regarding the limits of the present study, it should be mentioned that there was a lack of an established control group of patients with PCD, PP, and a Bishop score £6 and in which PG was used as a cervical ripening method. This intervention would have allowed the comparison of cervical ripening with PG or the Foley catheter. Cervical ripening with PGs in patients with PCD was not performed due to the existing controversy about PG use in this subset of pregnant women. This controversy was generated based on the data collected by Lydon-Rochelle in 2001,2 who observed a higher uterine rupture rate associated to PGs in patients with PCD. Thus, our hospital protocol contraindicates the use of PGs in patients with PCD. Another weak point of the present study is the fact that multiple gynecologists were involved in the patient’s examination, possibly resulting in interobserver variations of some parameters with a high subjective component, such as the Bishop score.

Interestingly, in this study, patients with and without a previous VD were enrolled. When the predictor variables to achieve APL were studied, the history of a prior VD did not increase the likelihood of APL, in contrast to other published reports.24,26 Moreover, the PCD for FI, when it was compared with the remaining PCD indications, was associated with a statistically significant reduction in the likelihood of APL. Similarly, the PCD for FI was associated with a decrease in the likelihood of VD when it was compared with other PCD indications, such as AP, RFD, or placenta previa, but it had no statistical significance when compared with PCD indications for NPL, CPD, or other fetal causes. Another variable which was inversely proportional to both the probability of achieving APL and reaching VD was the ultrasound CL measured prior to cervical ripening, although this association was not statistically significant. This is in accordance with an article published in 2018 by Marciniak et al.,27 revealing that a low Bishop score is associated with a reduced likelihood of VD, given that the Bishop score is low if the CL is high. Additionally, the present study revealed a lower likelihood of VD with increased maternal age (which was not seen for the likelihood of APL). Within the framework of the predictor variables, Heidi Kruit et al.28 published a paper in 2018, where cervical biomarkers, such as the insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1), matrix metalloproteinases (MMP), and MMPS inhibitors (TIMP) were studied to predict the likelihood of achieving APL. Although the authors observed some specific changes (an increase of IGBP-1 or a decrease of MMP-8 and MMP-9), they could not predict APL. Further studies should be carried out to unravel cervical biomarkers that could predict the achievement of APL and VD in patients with PCD, PP, and a Bishop score ≤6 prior to mechanical cervical ripening.

The prevalence of uterine rupture in patients with PCD varies between 0.5 and 2.9%, being higher if PGs are used (2.9–18%) (1–5,24). In the present study, no patient developed a uterine rupture, which is comparable with other safety studies regarding the use of the Foley catheter for cervical ripening in patients with PCD.1,3,4,24 The reported maternal-neonatal infection rate seen in the PROBAAT study29 was below 6%, which is in accordance with the present study. The total maternal-fetal complication rate associated to mechanical cervical ripening in patients with PCD in this trial was approximately 3%, suggesting that the Foley catheter is a safe technique for cervical ripening in patients with PCD. These findings are in accordance with previous observations.14–16,23 However, further studies with greater sample sizes are needed.

According to the results of the present study, cervical ripening with the Foley catheter in patients with PCD and PP should be more widely studied, not only regarding the cervical biomarkers that can predict VD, but also regarding its safety and effectiveness compared with PGs. Furthermore, it would be useful to analyze the suitability of one catheter over that of others for mechanical cervical ripening in pregnant women with PCD, PP, and a Bishop score £6.

Mechanical cervical ripening with the Foley catheter and subsequent oxytocin infusion in pregnant women with PCD, PP, and a Bishop score £6 is associated with the achievement of APL of approximately 80% (86/109) of the patients, and 47.71% (52/109) of the patients undergo VD.

Among the predictor variables to achieve APL, those PCD indications different to FI are associated with a statistically significant higher likelihood to achieve it. Likewise, CL prior to the Foley catheter insertion is inversely proportional to the likelihood of achieving APL. Thus, a higher CL is associated with a lower likelihood to achieve APL.

Regarding the likelihood to finish the pregnancy with VD, associated to the PCD indication for FI, it is reduced in a non-statistically significant way when compared with the remaining PCD indications. However, it only results statistically significant when it is compared with the indication for AP, RFD, or placenta previa. The CL and maternal age are inversely proportional to the likelihood of VD. Therefore, the greater CL and the advanced maternal age are associated with a lower likelihood of finishing the pregnancy with VD, although this is not statistically significant.

In conclusion, the present study reveals that the use of the Foley catheter for mechanical cervical ripening, with subsequent oxytocin infusion, is an effective method to achieve APL and VD in patients with PCD, PP, and a Bishop score £6. Furthermore, this study reveals that mechanical cervical ripening in this subset of patients is safe, given that no patients developed a uterine rupture. Interestingly, among the predictor variables for achieving APL, those PCD indications different than FI were associated with a statistically significantly greater likelihood of achieving APL.

None.

Availability of data and material: The dataset used and analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

None.

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

©2022 , et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.