eISSN: 2377-4304

Case Report Volume 12 Issue 5

1Pronatal Clinic (Bité Médica Hospital) México

2Female Health Clinic, Mexico

Correspondence: Vargas Hernández Víctor Manuel, Research Department, Hospital Juárez de México, Tel 01002611058

Received: July 26, 2021 | Published: September 29, 2021

Citation: Estuardo LIJ, Carlos DM, Daniela AR, et al. Propanolol as a treatment for deep infantile hemangioma: case report. Obstet Gynecol Int J. 2021;12(5):302-304. DOI: 10.15406/ogij.2021.12.00596

Background: Infantile hemangiomas (IH) are common neoplasms composed of proliferating endothelial cells. The duration and the growth rate are variable; some grow very poorly, while others grow rapidly and at an unpredictable rate. Despite the relative frequency of IH and the possible severity of complications, there are currently no uniform treatment guidelines. Although most are not worrisome, about 12% of IHs are significantly complex; propranolol has been adopted as a treatment.

Objective: Report a clinical case of lactanate with hemangioma treated with propranolol.

Case report: A healthy newborn is presented, with the presence of small telangiectasias in the right hemicneck without association with obstetric trauma; of a healthy 31-year-old mother; During its evolution at 3 months of age, the area covered with telangiectasias turned deep blue and the growth of a protrusion began, ultrasound and angioresonance, showed soft tissues of the posterior cervical space a lobulated mass of 9.1x4.1x4.9cm in its longitudinal and transverse diameter respectively, diagnosing it as a deep hemangioma; which was treated with propanolol.

Discussion: Asymptomatic newborns with infantile neck hemangiomas are clinically controlled for the first six months of life, 60% of them develop life-threatening airway symptoms; the identification of the hemangioma was due to its rapid growth and not due to the alteration of surrounding structures that put the well-being of the infant at risk. Regarding the application of Propranolol, its administration was immediately after its identification, to avoid future complications.

Conclusion: administration of propranolol systemically eliminates the characteristic color and reduces the size of the hemangioma.

Keywords: hemagioma, propanolol, imaging, management

Infantile hemangiomas (IH) are common benign tumors composed of proliferating endothelial cells, their duration and growth rate are variable; some infants will have poorly growing hemangiomas, others grow rapidly and at an unpredictable rate, most are risk-free, 12% are complex.1

Vascular alterations of blood and lymphatic vessels are heterogeneous and the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA) has classified them as tumors and vascular alterations. Among the vascular tumors are HI, the prevalence in the general Caucasian population of 4.5% being more common in women, associated with a possible synergy between the vascular endothelial growth factor and estradiol. They generally manifest in a single form of erythematous or erythematous-violaceous coloration, are of variable size (up to 30cm) and generally do not appear at birth. They usually appear in the first four weeks of life, 80% of their weight between months 3 and 5, with a slow growth phase between months 6 to 9 and their involution begins at this time, 20 to 40% of patients leave changes residuals such as telangiectasias, fibrofatty tissue, redundant skin or pigmentation changes.2–5

The diagnosis is basically clinical; Contrast MRI imaging evaluation is used to define the type, size, and extent of the lesion;6 The treatment of a patient with IH is individualized, depending on factors such as size of lesion, location, presence of complications such as ulceration, risk of scarring or disfigurement, age of the patient, rate of growth or involution at the time of diagnosis, risks and benefits of administering the treatment.7

We present the case of an infant with a diagnosis of deep IH in connection, treated with propranolol.

A healthy 31-year-old mother, pregnancy 1, delivery 1, normal pregnancy course, obtaining by eutocic delivery at 40.4 weeks of female gestation with APGAR 9 and 10 in minutes 1 and 5, weight of 3005g and height of 48cm.

The healthy newborn which apparently does not present any alteration, only small telangiectasias were observed in the right hemicneck, which was initially associated with possible trauma resulting from childbirth, Figure 1.

Figure 1 Image of the 4-day-old newborn, in which no protrusions are observed on the right hemicneck, indicating the development of a hemangioma.

At three months of age, the area covered with telangiectasias turned deep blue and the growth of a lump began, Figure 2; At 4 months to 3 weeks of age, an increase in the volume of the right hemicneck is observed, clinical evaluation is performed using abdominal ultrasound with Doppler to rule out alterations, observing liver with well-defined borders, bile ducts (intra and extrahepatic), vascular pattern, pancreas, kidneys, cortex of the medulla, bladder and intestinal loops with normal parameters. In addition, the electrocardiogram did not find any alteration (PSVD 15mmHg and LVEF 6% AF32%) and the hemostasis profile showed normal values except for a decrease in activated partial thromboplastin time (18.1 second). Angioresonance is requested, showing soft tissues of the posterior cervical space, between the muscle masses of the sternocleidomastoid and the long muscle of the head in the upper and middle third, towards the distal third that involves the muscle mass of the trapezius and that extends into the tissue. subcutaneous cellular. The image is lobulated with measurements of 9.1x4.1x4.9cm in its longitudinal and transverse diameter respectively, it is isointense in T1, heterogeneous hyperintense in T2 and fat suppression with multiple areas of signal voids in relation to nutritional vessels, it was also observed Large-caliber nutrient vessel dependent on the right subclavian artery. (Image 2A, 2B, 2C, 2D and 2E).

Figure 2 A, B) show infantile hemangioma at 4 months of age. C) Angioresonance, where it can be seen how the hemangioma is inserted below the hemicneck and D, E) three-dimensional reconstruction of the magnetic resonance image, the structure shows the origin of branching of the hemangioma.

With the results of the angio-resonance study, it was observed that the patient had a deep alteration in the vascular system of the upper part of the trunk, diagnosing it as deep IH

Hemangioma management

The treatment can be topical and systemic, within the topical treatment are timolol, propranolol, imiquimod, topical corticosteroids, brimonidine and lasers, finally, in the systemic treatment beta-adrenergic blockers, propranolol, atenolol, systemic corticosteroids can be used, vincristine and IFN-α 2a or 2b.6

Propranolol is a synthetic β-adrenergic receptor blocking agent that is classified as non-selective because it blocks β-1 and β-2 adrenergic receptors. Chronotropic, inotropic, and vasodilatory responses decrease proportionally when propranolol blocks the β receptor site, resulting in a decrease in heart rate and blood pressure, and the mechanism of action of propranolol on HI has not yet been clearly defined. Some of the proposed hypotheses include vasoconstriction, decreased renin production, inhibition of angiogenesis, and stimulation of apoptosis. Medical management is highly individualized, and oral propranolol treatment is considered in the presence of ulceration, impairment of vital function (ocular involvement or airway obstruction), or risk of permanent disfigurement;8 The patient started with 10mg tablets of propranolol, taking: first week: ½ tablet in the morning, second week: 1 tablet in the morning and ½ at night, and third week: 1 tablet in the morning and 1 at night, continuing in this way until the doctor indicated the suspension of the medication. A week after the start of treatment, the diagnosis of deep IH was confirmed, because the medication with propanolol allowed the reduction of the hemangioma by up to 50%.

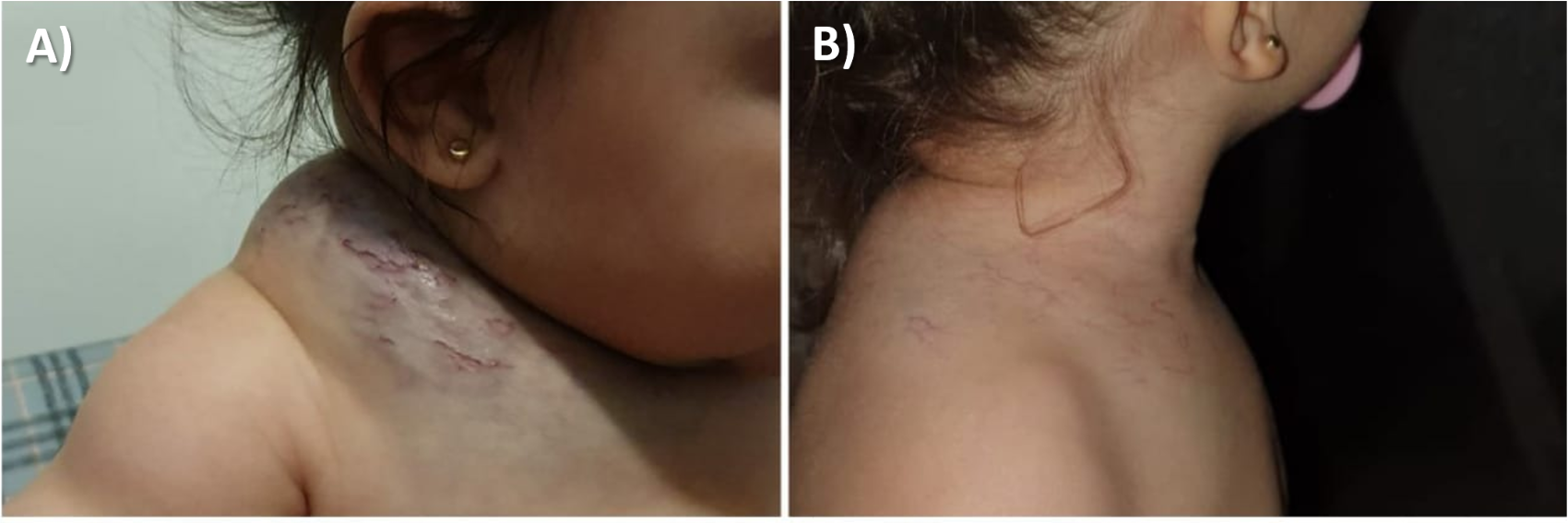

After 1.4 years of treatment, treatment reduction began, because the IH reduced its size until it was completely flat, with only a small amount of telangiectasia being observed, Figure 3.

Figure 3 A) Infantile hemangioma (4.3-week-old baby) and B) disappearance of infantile Hemangioma, with traces of telangiectasia (1.4-year-old baby).

Finally, 4 months after suspension of treatment (1.8years of age), it was possible to observe recurrence with small growth of HI, making the decision to resume treatment with Propranolol. Currently, at 2 years of age, the patient continues with propranolol 20mg/day with a totally flat hemangioma and a small amount of telangiectasia.

HI is the most common vascular tumor affecting children that appears in the first 2 weeks of life; as was our case and a proliferative phase continues that continues during the first year of life. The characteristic proliferative phase of IH occurs in the first year of life, with maximum growth during the first 6 months after birth, during which it increases in size, depth, and color, with an increasing possibility of bleeding and ulceration. The involution phase begins thereafter and can continue for up to 5 or even 10years.8

IHs are frequently located on the head and neck (80%), followed by the trunk and extremities.9 Most are small and do not require treatment,10 their location, size and distribution can affect neighboring structures, which can be associated with abnormalities that affect the integrity of the baby. It is estimated that 1–10% of HIs are associated with significant morbidity, mainly in the form of concomitant malformations.8,11–19

In IH that do not affect adjacent organs, the application of propranolol improves the aesthetics of the patient and reduces the risk of possible complications in the future. The application of 2mg/kg/day of Propranolol systemically, eliminates the characteristic color and reduces the size of the HI, is a safe treatment and has no adverse effects, for which observational studies agree on its use as first-line treatment.

None.

None.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

©2021 Estuardo, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.