eISSN: 2377-4304

Case Report Volume 13 Issue 5

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, The Brooklyn Hospital Center, USA

2St. George’s University- School of Medicine, True Blue, Grenada West Indies

Correspondence: Neil Patel, MD, The Brooklyn Hospital Center, 121 Dekalb Ave. Bk, NY, 11201, USA, Tel 303-919-7668

Received: August 24, 2022 | Published: September 14, 2022

Citation: DOI: 10.15406/ogij.2022.13.00661

Trauma is not uncommon in pregnancy. Trauma and its complications in pregnancy include premature rupture of membranes, pelvic fractures, uterine rupture, placental abruption, direct fetal injury, fetal death, or maternal death. We present a case of placental tear and bleed secondary to physical trauma and domestic abuse with counter-coup injury. This case report highlights a unique case in which the patient endured physical abdominal trauma at 32 weeks, who presented for decreased fetal movement and pelvic pressure, but denied vaginal bleeding or decreased fetal movement. Findings were significant for hypofibrinogenemia and change in ultrasound placental findings in the setting of reassuring fetal monitoring consistent with concealed traumatic abruption. This unique presentation adds to the literature because it will increase provider awareness of the subtle signs of intra-placental abruption.

Keywords: trauma, pregnancy, abruption, intra-placental, cesarean section, preterm abruption, domestic violence

C-section, cesarean section; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; AFI, amniotic fluid index; PT/PTT, prothrombin time/partial thromboplastin time; NST, nonstress test; BPP, biophysical profile; PRBC, packed red blood cells

Trauma is not uncommon in pregnancy. Trauma and its complications in pregnancy include premature rupture of membranes, pelvic fractures, uterine rupture, placental abruption, direct fetal injury, fetal death, or maternal death.1,2 Up to 1% of pregnancies suffer placental trauma. In most cases, motor vehicle accidents and falls account for most ruptures, however intimate partner violence plays an important role. Most notably associated with partner violence is blunt trauma. One-third of pregnant women treated for trauma suffer intentionally inflicted injury.3 Blunt trauma can cause placental abruption or tears secondarily to the deformation of the elastic myometrium around the inelastic placenta.4 We present a case of placental tear and bleed secondary to physical trauma and domestic abuse with counter-coup injury.

Here we present a unique case of third-trimester traumatic placental abruption in the setting of trauma and the absence of typical maternal-fetal clinical presentation, except for low fibrinogen, concerning for large placental tear and intraplacental hemorrhage.

Initial presentation

A 34-year-old P3013 at 32w2d presents to the emergency room, complaining of pelvic pressure and pain twelve hours after an altercation with her partner. The patient reports verbally arguing with their partner, which turned physical, resulting in the patient being pushed to the ground and kicked/stepped on in the abdomen and pelvis repeatedly. The patient was pushed to the floor and landed on her coccyx with significant force. After a few hours, the patient reported decreased fetal movement and aching pelvic pressure, which is worsening in intensity. On presentation, the patient denies leakage of fluid, vaginal bleeding, or regular painful contractions.

Initial maternal evaluation showed stable and normal vital signs, afebrile, normotensive, normal heart rate and rhythm without tachypnea. The abdominal exam showed a soft, non-tender, non-distended gravid abdomen, no suprapubic tenderness, and no back pain or tenderness was elicited. Fetal movements endorsed. No vaginal bleeding or gross pooling was noted. The cervical evaluation revealed the cervix to be closed, long, and posterior. Initial bedside ultrasound fetal evaluation determined a fetal weight of 2,064 grams, amniotic fluid index (AFI) 13cm, cephalic fetal position, and a right lateral placenta. Ultrasound of the placenta showed a normal placental thickness (>5cm), which was homogenous and isodense. Electronic fetal monitoring showed a reactive fetal tracing with a baseline of 140 bpm, accelerations present, no decelerations present, and no contractions noted. Initial labs included: type and screen: AB-negative, positive Anti-D due to Rhogam, complete blood count: hemoglobin of 9.5g/dL, hematocrit of 28%, platelet count 186 x10^9mcL, prothrombin time/partial thromboplastin time (PT/PTT) 10.4sec/23.6 sec, fibrinogen 50mg/dL (repeated twice).

Re-evaluation after 12 hours

The patient remained asymptomatic, vitally stable, and denied all obstetrical complaints, not limited to vaginal bleeding, abdominal pain, and decreased fetal movement. The subsequent fetal evaluation showed a reactive nonstress test (NST) with a baseline of 140bpm. Accelerations were present, no decelerations were present, and no contractions were noted on monitoring. The biophysical profile (BPP) was repeated and found to be within normal limits, 8/8, and showed the AFI was stable at 13cm. The placental evaluation was significant for a diffusely globular placenta that had a thickened appearance. There were no signs of placental abruption or separation noted (Figure 1). No areas of hypo- or hyper- density were identified. Repeat laboratory studies included: hemoglobin 9.2g/dL, hematocrit 27%, platelets 180x10^9mcL, PT/PTT 10.6sec/24.7 sec, fibrinogen 231mg/dL, repeat fibrinogen 101mg/dL, d-dimer was >4.40ng/mL. Hematology-Oncology was consulted for low fibrinogen levels and recommended evaluation of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) as well as transfusion of cryoprecipitate, fresh-frozen plasma, and packed red blood cells (PRBCs) as needed. The diagnosis of post-traumatic placental abruption/tear with low fibrinogen and early DIC was made. Due to the low level of fibrinogen in the setting of stable reassuring fetal evaluation, NST 10/10, the patient was transfused with four units of PRBCs and ten units of cryoprecipitate. She was taken for an urgent cesarean section.

Operative findings

A low segment transverse cesarean delivery was performed. Delivery of the baby was significant for APGAR 9 at one minute and 9 at five minutes and the patient was transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Operative blood loss was estimated to be 700cc. One gram of tranexamic acid was given intra-operatively. The patient was transferred to recovery in stable condition. At the time of delivery, the placenta was noted to be grossly engorged with blood and dark blue-red in color. There was a loss of normal cotyledon architecture, and a three-centimeter placental tear was noted on the fetal side (Figure 2). Fetal bleed screen: Kleihauer-Betke Hemorrhage reported as 10ml.

Pathology findings

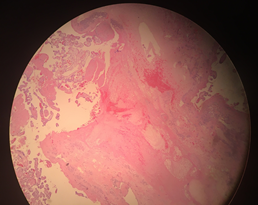

Gross findings: Total weight was 452grams. Umbilical cord with three vessels. Unremarkable membranes. Placenta was noted to have subchorionic fibrin plaques throughout. A mild degree of spiraling was noted. The maternal surface was dark red with complete cotyledons. Cut sections showed a dark red, spongy surface. No hematomas were noted. Microscopic findings: Sections showed intraplacental fibrin plaques with fresh and decidual hemorrhage (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Microscopic findings: Sections showed intraplacental fibrin plaques with fresh and decidual hemorrhage.

Post-Op recovery

After 24 hours post-procedure, the patient was noted to have a postpartum hemorrhage. The patient denied all symptoms of anemia and vital signs remained stable. Uterotonics were given: 40 units of oxytocin and 1000mg of misoprostol. The patient was also given an additional two units of PRBC. Post-transfusion labs showed a hemoglobin of 10.5g/dL, hematocrit of 32%, and fibrinogen of 188mg/dL. Vital signs remained within normal limits throughout the remainder of the post-operative course. The cesarean incision remained clean, dry, and intact. The baby had an uneventful NICU stay. The patient and baby were discharged home in stable condition.

Trauma in the setting of pregnancy raises concern for abruption; either acute or delayed. Patients typically present for evaluation after hitting their gravid abdomen accidentally or through deliberate intent, as present in this case. Typical signs may include painful or painless vaginal bleeding and/or decreased fetal movement. On presentation, patients are evaluated by physical exam, ultrasonography, and external fetal monitoring. In the setting of acute abruption, vaginal bleeding may be noted, with fetal heart rate changes requiring prompt intervention. Conversely, the placental bleed may be concealed, vaginal bleeding may not be present.3 In the case of a placental tear, as in our patient, there may be a slow intra-placental bleed with thickening and engorgement of the placenta. This may be associated with minimal symptoms except for ultrasound findings of a thickened echogenic placenta (Figure 1) or laboratory findings, such as a drop in hematocrit and/or low fibrinogen.

In our patient, the signs and symptoms were minimal, despite a significant intraplacental bleed, blood loss anemia, and profound hypofibrinogenemia. The diagnostic tools included a clear history, placental ultrasound, and laboratory assessment. We attribute the intra-placental bleed to the placental tear, most probably to the counter force generated after the patient was pushed very hard to the floor on her coccyx. The force of the posterior placenta against the patient's sacrum was probably the cause of the placental trauma, and this has been described by Crosby et al.5 and is outlined in Williams Obstetrics.3,5

Much is known about trauma and abruption in pregnancy, however initial findings of isolated low fibrinogen, with reassuring fetal evaluation, prompts the need to investigate the pathophysiology and presentation of this unique abruption. Traumatic abruptions are more likely associated with concealed abruptions; generating higher intrauterine pressures, with deformation-reformation injury, secondary to inelastic myometrium presenting with associated coagulopathy compared to nontraumatic abruption.5–7 The tear caused is linear or stellate and is caused by the rapid deformation-reformation injury (Figure 4).5,6

In conjunction with traumatic abruption, gross evaluation of the placenta and microscopic pathology supports a rapid deformation-reformation injury when comparing the gross placental tear (Figure 2) to that outlined by Crosby et al.5 (Figure 4). In a simultaneous process, the abruption hemorrhages into the placental tissue, ultimately leading to the introduction of placental tissue factor and other procoagulant substances into maternal circulation.8,9 Subsequent activation of the tissue-factor-dependent coagulation pathway is consistent with the current body of literature, which implicates this pathway specifically in the pathogenesis of DIC.10–12 In addition to a procoagulant state, the counter-regulatory factors such as tissue-factor pathway inhibitor, antithrombin III, and protein C have also been shown to have impaired function in the setting of DIC secondary to trauma.10,13,14 The net result is large-scale production of thrombin leading to conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin within the vasculature leading to obstruction.8,12,15 The use of fibrinogen levels as a diagnostic lab value would seem intuitive given its conversion to fibrin by thrombin following the activation of the coagulation cascade;15 however, it is also a positive acute-phase reactant and may remain in the normal range despite active coagulation.13 Despite its limitation as a sensitive diagnostic tool, changes to fibrinogen levels, particularly serially declining levels, should raise clinical suspicion for DIC.9

We feel that this case report adds to the literature because it will increase provider awareness of the subtle signs of this particular type of abruption in patients sustaining physical violence and domestic trauma.

None.

None.

Author declares there is no conflict of interest exists.

©2022 , et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.